April 22, 2022

Designing from the Earth up: IDEO puts long term first

In 1980, Steve Jobs asked a new design firm to develop a mouse for what would be one of the first personal computers to feature a graphical user interface, the Apple Lisa. The life span of this innovative desktop computer was short, but the legacy of its mouse design, which abandoned an expensive mechanism found in earlier mice in favor of a more easily manufactured component, can be seen in many of the mechanical mice used today.

The design firm behind the innovative mouse was David Kelley Design, the precursor of the innovation and design consulting firm IDEO, which was established in 1991 when designers David Kelley, Bill Moggridge and Mike Nuttal merged their companies. The firm has since expanded well beyond the scope of industrial product design, working on projects that encompass everything from health care to government and education.

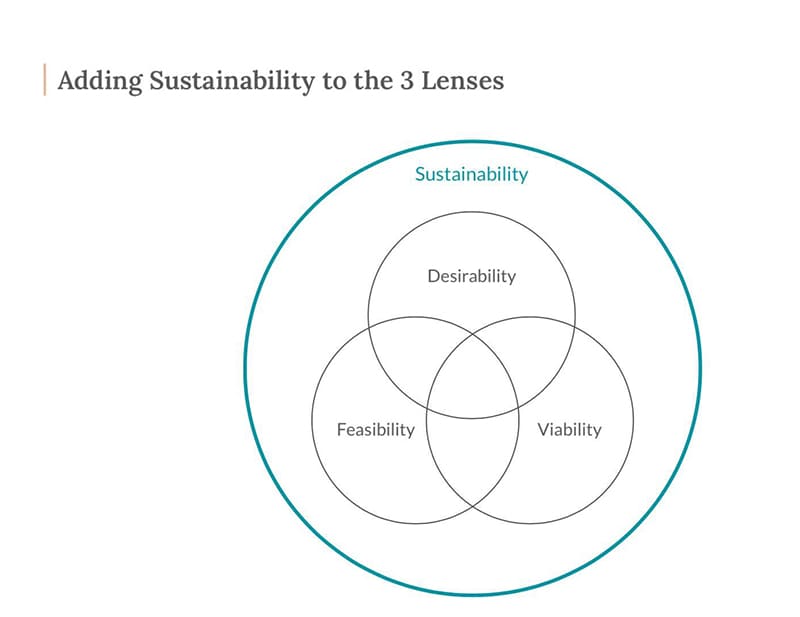

Regardless of the field, central to IDEO’s design philosophy is the notion of human-centered design, an approach to design that integrates the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success. In the 18th iteration of the Japan Times Sustainability Roundtable, host Ross Rowbury sat down with Amelia Juhl, design director of IDEO Tokyo, to discuss human-centered design and its role in achieving sustainable solutions.

Skin care, kitchens, clean air

Juhl and IDEO have worked with various companies and organizations to innovate services and products in a wide array of fields, ranging from skin care products and agriculture to aerospace and futuristic kitchen tables. In 2015, IDEO worked with Ikea on a project to envision the future of the kitchen, which resulted in a prototype table that suggests recipes based on ingredients placed on its surface. IDEO Tokyo has also worked with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency on the Future Blue Sky project, a research and development project to reduce congestion and pollution and improve access to renewable energy.

As a design researcher, Juhl hones in on how people interact with a product or service. This interaction varies in complexity depending on the target of the design. “Initially, design was done by experts,” she said. “A product designer would think about how to make a cup or chair beautiful. Then an engineer would come in and take away all the interesting bits so it could be scaled for manufacturing.” Juhl explained that design researchers serve a different role, getting involved earlier in the process to talk to end users, or to all those who are touched by the designs, and identify aspects that can be improved. This is especially important when designing services, systems and businesses, she said: “With many people involved, the process of design allows us to bring people into the process in a way that serves all people.”

It may seem like common sense for the creators of a product or service to reach out to end users, but this is not always the case, Juhl observed. She recalled how one of her clients, despite having many years of experience creating medical devices, had never actually spoken to the people using them. “When we had a kickoff, I asked the clients to put the medical device on themselves. It was actually the first time the engineers had ever done that,” she said. “Clients often don’t have a direct connection with how their products are being used.”

Distinguishing needs, desires

The next step in design is taking responsibility for the entire system in which a product or service is created, encompassing everything from the raw materials to the effects on workers, consumers and the planet, Juhl said. “We need to start thinking a little bit more about whether we’re creating long-term health, to think about the difference between needs and desires,” she said. To illustrate this distinction, Juhl drew from her experience working on an agricultural project. “That project opened my eyes to our aging farming population, our unstable climate and the degradation of our soil and ecological health. What we are doing in agriculture is destabilizing our health in our bodies, and on land, for ourselves and generations to come.”

Shortly after, Juhl worked on a technology project that she described as “technology for technology’s sake.” While acknowledging that these projects have value from a human desirability standpoint, she posited an often overlooked question: At what cost? “These require more infrastructure, more energy and more rare materials,” she said. “Who are we leaving behind in this process? If you think about how all the economic gains we’ve had in the last few decades are concentrated on a few, and that half the world is living on $5.50 a day, the thing we were working on starts to feel a little superfluous.”

Juhl explained that designers, “knowing that it’s so much easier to tap into our weakness, manufacture a need and capitalize on our willingness to pay,” need to check themselves and ensure they are creating long-term health for communities and the planet, not just short-term happiness. Of course, this is easier said than done, as what is good for the planet often conflicts with the incentives of our economic structures. “We think we can’t change any elements of the economy, but actually it’s nature that we cannot change,” she said. “We need to live in harmony with it.”

Aligning with the planet

Design research emphasizes the act of speaking with end users to understand their needs. But what about planetary needs? Juhl observed that although we cannot speak to the planet, there are clear, intuitive planetary needs with which we can align our decisions. To this end, Juhl is exploring how to incorporate tangible core sustainability principles into her conversations with clients. “For example, don’t increase concentrations of synthetics into the biosphere faster than it can be naturally processed by the Earth, or don’t destroy ecosystems or habitats faster than they can replenish themselves,” she explained. “These are things you cannot violate, and they apply universally to any company.”

The application of such principles necessitates organizational transformation, which must be spearheaded by bold leadership, Juhl said. “When you set a big goal, you’re actually, as a leader, creating the space for creativity to flourish and providing permission for experimentation.” She mentioned Unilever and Patagonia as examples of organizations that have demonstrated such bold organizational leadership. “As much as I would like to start this process, I cannot. It really needs to start with visionary, courageous leaders who commit to taking responsibility for their entire business system.”