September 22, 2023

Problems drive sustainability leader Sawyer to solutions

Thriving in the jungles of Costa Rica without electricity or running water provided Kai Sawyer with a new perspective on how to coexist with nature. “I saw more monkeys than people,” explained the multilingual sustainability practitioner, “and they taught me how to live, so I had to reprogram myself.” Sawyer had an epiphany: Only humans create trash or work for money, and by seeing ourselves as separate from nature we create problems that modern society doesn’t need to have.

Born in Japan and raised in Niigata, Hawaii and Osaka, Sawyer attended the University of California, Santa Cruz, where, as co-chair of the Education for Sustainable Living Program, he trained students on student-centered education and sustainability activism. Sawyer now lives at the Peace and Permaculture Dojo with his family in the Chiba city of Isumi, where he teaches sustainable living and design, and is also the founder of Tokyo Urban Permaculture, a movement devoted to regenerating the urban ecosystem through growing food and changing the culture in Tokyo. He teaches sustainable living, nonviolent communication, how to heal depression and trauma, and mindfulness at universities, conferences and community gatherings around the world.

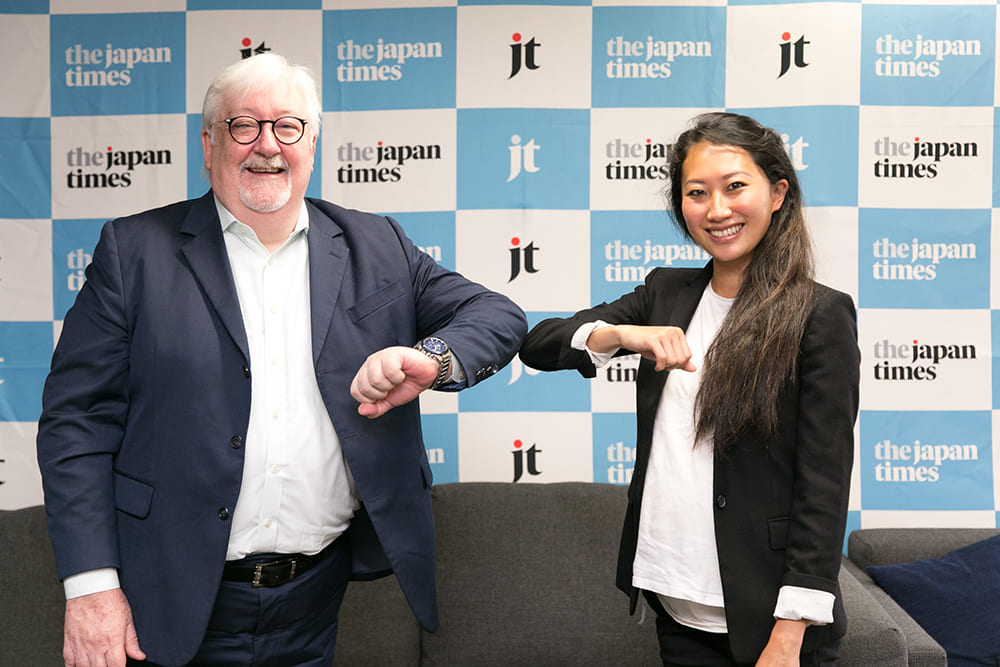

Sawyer took time out from his busy schedule to sit down with Ross Rowbury for the 33rd incarnation of Roundtable for The Japan Times to discuss sustainable living, “guerilla seed-planting,” mental health and gaining new perspectives, among other things.

Regenerative thinking

Rowbury began by asking Sawyer why he began Tokyo Urban Permaculture and what it is about. “Yeah, that’s a hard one,” Sawyer began. “The way it started was that in my journey trying to figure out how to live sustainably, I came across permaculture. Having lived in the jungle of Costa Rica, I realized this was the perfect way to live. If you have food, water, soil regeneration, living just gets better and better.”

After the Fukushima nuclear disaster and meltdown in March 2011, Sawyer found himself drawn back to Japan, for he saw it as an opportunity to rally. “There’s a fun phrase in permaculture which is ‘The problem is the solution,’” he explained. “The energy that drives people involved in permaculture is to find solutions to problems. You’re not just trying to find a nice piece of land and live in utopia, you’re trying to make things better. It means to engage with the biggest problems, and use regenerative thinking to make a horrible situation beautiful. So I found my perfect challenge. I thought, OK, I’ve found my utopia, but I’d found it in a global-scale disaster, and now what am I going to do about it?”

Shifting nature’s narrative

For Sawyer, the Fukushima meltdown was just one part of modern society’s regeneration puzzle. “After Fukushima, I flew into Tokyo just as people were trying to leave, and the first thing I wanted to figure out was, how do we change our culture, how do we help people reconnect with nature? As much as humans belong in nature, we have decided that we are not part of nature.”

Sawyer believes that to achieve this it will be important to change the stories that we tell ourselves. “Humans, we live in stories,” he explained. “These stories basically guide us — the things we talk about, the way we live, the way we do business, the way we organize societies. Then there’s a field called ‘systems thinking,’ and at the very bottom of systems thinking is what is known as ‘mental models.’” As much as he hopes to get people excited about permaculture, he also hopes that, based on his transformative experiences in Costa Rica, he can change societies’ basic mental models in terms of our relationship with nature so we understand that we can only come up with the solutions we are seeking if we accept that we are part of nature and fundamentally change how we live.

Doing something tangible

For Sawyer, mental models without action are just great stories. He encourages “guerilla” gardening and seed-planting. He happily passes out seeds to visitors to his Permaculture Dojo with instructions to find some land and spread some seeds. “It’s what all animals do, whether it’s monkeys or birds, often illegally,” he joked. What’s important is for people is to challenge their beliefs and to work with nature: “It’s kind of subversive but fun.”

Sawyer explained that permaculture is not just about food, but also energy design, and that in the past, most homes were passive solar homes, oriented toward the sun to be warmed in winter but also shaded to stay cool during summer, assisted by air flowing through the house. “Design is huge — if we designed all our systems to be energy-cycling, we wouldn’t have to waste so many resources.”

A world without enemies

Living in Costa Rica, Sawyer had to quickly realign his understanding of community. “When I was in my 20s, and really excited about community and sustainability, community meant people who were similar to me,” he said. “But after my house was invaded by ants or cockroaches, I realized I had to unlearn everything and accept that the house is just Earth.” The experience gave Sawyer insight into the futility of fighting “pests”: “There’s always another pest — how much do we want to keep fighting? Just like people — there’s always someone you don’t get along with, so how do we create a world where we don’t have enemies?” He found that he needed to unlearn his constant habit of trying to achieve something, be productive and prove himself. “What was the point?” he said with a laugh. “I was living in the jungle with creatures who didn’t care.”

Unlearning and belonging

One of Sawyer’s priorities with urban permaculture projects is trying to ensure that participants in his projects feel like they have somewhere they belong. “Our modern society is always telling us that we need to prove that we belong, but if nature is your home, and you belong in your community without having prove anything, it becomes a form of empowerment when people feel like they belong, and it has huge implications for mental health, especially in a big city like Tokyo,” he said. “It creates a sense of belonging, a sense of mattering, that they can go out and change the world in small, meaningful ways.”

For now, Sawyer’s goals are to slow things down. “I used to be the eco-warrior trying to change the world, but I’m trying to slow things down,” he insisted. “One of the most important things is living a holistic life. I want to slow down but increase the quality of what I’m doing.”