December 16, 2022

IGES: Preserving biodiversity with science, foreteller insects

How blind are we to things too big to see directly? Take the environment — why should people care? Our muddled perceptions can make it grueling to find the right balance between individual well-being and conservation of nature. Falling biodiversity — the variety in the life around us, from microbes on up — has severe repercussions for human well-being. As species go extinct, we lose the food, clothing, medicine and more that they can give us, some of it lost before ever being discovered.

Yasuo Takahashi, research manager of the biodiversity and forests area at the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), joined Ross Rowbury at The Japan Times Sustainability Roundtable for its 25th iteration. They discussed the institute’s work in the realm where science and policy intersect to formulate strategies concerning biodiversity, climate change, and sustainable consumption and production.

Serendipitous events in life

Serendipitous events often steer us on unexpected routes in life. As a youth, Takahashi enjoyed nature and liked birdwatching with his grandparents. He completed his four-year undergraduate studies in a Hokkaido marsh, where he became enthralled by the dispersion of prevailing plants. Rowbury noted that people who at a young age have a robust connection with nature tend as adults to have a much-heightened sensitivity toward environmental challenges and sustainability issues.

The underlying human-nature dichotomy is that although people seek nature’s irrefutable healing benefits, they still fear its lurking — and often unpredictable — threats. People in developing countries are more directly reliant on natural resources. Knowing that led Takahashi to apply for a two-year volunteer project in Malawi that the Japanese government had arranged, for which he “luckily” — as he humbly claimed — got selected. “I stayed in a tiny village in Malawi, one of the poorest countries in the world, which bordered a lake close to a mountain. Though people were poor, they never abstained from smiling. Their source of happiness and kindness was a paradigm shift for me,” Takahashi said.

Once again, serendipity — perhaps life’s mesmerizing sauce — played its unsystematic role. Takahashi’s visit to seek a deeper understanding of the African environment (an external trek) unpredictably turned into an internal hike imposing the query: Are we overcomplicating the simple process of happiness?

Fishing for alternatives

People in Malawi were very dependent on the lake and its surroundings for food and other resources. “They overfished in the lake and cut plenty of wood for cooking. With their increasing population, they have been expanding the deforested areas,” Takahashi said. The strain that overpopulation has put on nature is significant, and overfishing one species may destroy a resource for another, with flow-on effects.

Rowbury wondered how an understanding of the issues could be translated into practical strategies. Takahashi explained that solutions are born “by understanding human drivers and human activity.” Raising an eyebrow, Rowbury seemed to be thinking about how quite difficult it can be to create policies that alter how people interact with nature so they don’t burden the land. “Everyone has been fishing in Malawi the same way they have always done it,” Rowbury said. “It’s just that the number has increased. People may rebel, saying, ‘Our grandparents have done it this way,’ and there is no reason why they shouldn’t do it similarly. On an individual basis, it’s tough to understand the impact one is having. Yet on a collective plane, the impact is quite serious.”

Rowbury later asked the question, “So how do you convince people to change how they interact with nature, and how do you get them to adopt new behaviors?” Takahashi emphasized the significance of having alternatives “because fishermen go fishing for income, and if they can’t go fishing, they have no income. So they would need alternatives to sustain their survival (before anything else), like having protein substitutes such as soybean rather than meat.”

Taking action in the real world

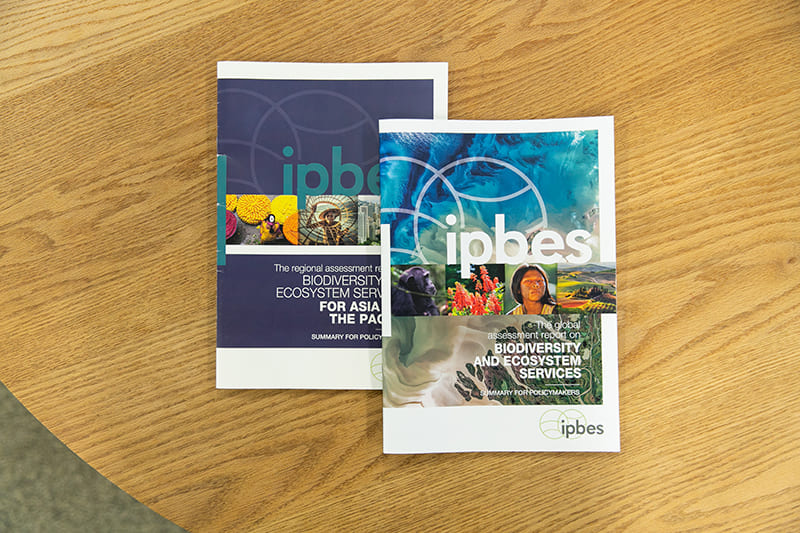

One can’t save nature only by studying it, Takahashi said: “Studying nature is vital to progress our relationship with it, but my preference leans towards further proactivity in the real world.” Rowbury stressed the importance of a solid knowledge base, saying, “Without the knowledge base, we can’t work out the issues and potential solutions and ultimately can’t get started.” Takahashi recognizes the value of scientific evidence, particularly when sharing it for the sake of reaching a global agreement, because people in diverse parts of the world have different understandings of nature. He also thinks direct experience with nature is pivotal to understanding complexity that a model might fail to provide.

Rowbury noted that the concrete objectives that societies require in their policies spring from scientific understanding, so it is safe to say that a combination of scientific analysis and field experience provides the link to get a consistent policy with which people can agree.

Local knowledge tests science

Culture and science seem to have a one-sided love relationship. Though almost all cultures cherish science, science is inclined to ignore culture as containing mythologies that go untested and are passed down through sentiment.

Takahashi mentioned the value of working scientifically in tandem with indigenous elements and local knowledge of nature. Rowbury recalled a personal experience with a shopkeeper in the northern part of the Kanto region who told him it would be a cold winter that year. “How do you know?” Rowbury asked. The merchant told him of an insect that could predict the level of snow in the coming winter and lay its eggs just above that level. If you see its eggs high up on tree trunks, there will be a lot of snow.

“Understanding nature is associated with the tradition — something weathermen never broadcast, but comes from living in harmony with the natural environment. The insect may be more accurate than the long-term weather report,” Rowbury said. Praising nature, he continued: “It is so fascinating because it is so broad in terms of diversity. Nevertheless, sometimes you need some degree of simplicity to offer an easy understanding of that biodiversity.” Takahashi nodded and spoke of how almost 80% of Japanese people reside in urbanized areas, “hence there is a huge gap between our lives and nature. From that vantage point, it wouldn’t be easy to empathize with biodiversity.”

One of the primary ways for people to grasp the issue’s immensity is to get close to nature. Although people in the recent pandemic years had no choice but to stay home, many have also realized there is no need to live in the city, especially those working from home. One might finally have the chance to abandon urban living — convenient but aggravating, with its wires and relentless ads — to be closer to nature.