May 29, 2021

Three firms make business strategies sustainable

Contributing writer

INDUSTRIAL GROWTH PLATFORM, INC. (IGPI), MANAGING DIRECTOR

“ESG” stands for environmental, social and governance issues — and although many Japanese companies have made strides in adopting higher standards of corporate governance, firms that have truly embraced environmental and social metrics of value are still relatively few and far between.

Moderator Naonori Kimura made this observation as he introduced the three participants in the second corporate session of the Japan Times ESG Symposium on May 13. They were from Suntory Holdings, Toyota Motor and Mercari, each of which has incorporated environmental and social goals into the core of its business strategy.

Suntory and Toyota are venerable giants of Japanese business — founded in 1899 and 1937, respectively — and have frequently adapted to changing circumstances during their long histories. In contrast, Mercari was founded in 2013 and has seen explosive adoption of its platform as users resonate with its vision of a “circular society” of less consumption and more reuse. How do these companies approach their ESG goals? The panel participants from all three emphasized the role of long-term vision and thinking holistically about the social impacts of their business as keys to pursuing their sustainability strategies.

Beyond the bottom line

SUNTORY HOLDINGS LIMITED, SENIOR GENERAL MANAGER OF CORPORATE SUSTAINABILITY DIVISIONPRESIDENT AND CEO

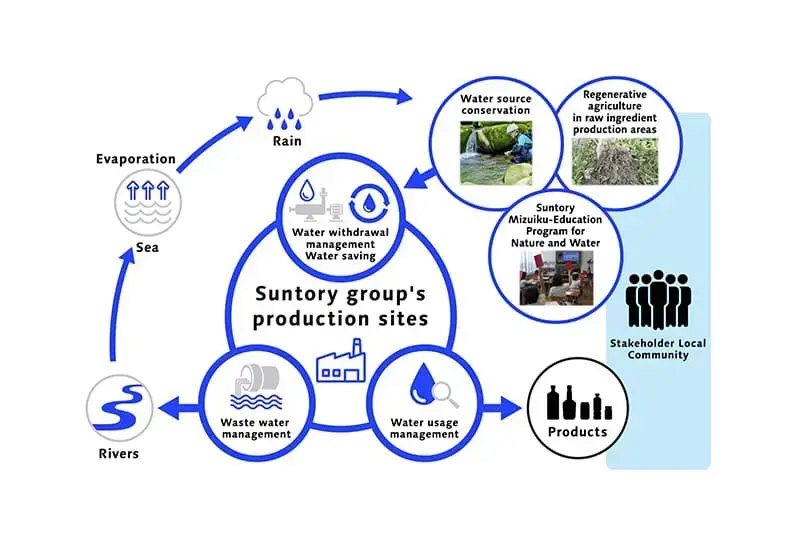

As a beverage manufacturer, Suntory’s business stretches from harvesting natural resources to production and finally delivery to consumers. In 2019, Suntory adopted a new sustainability vision that covers all of these areas, with particular focus on water sustainability, achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions across the entire value chain by 2050 and transitioning away from PET bottles derived from virgin petroleum-based materials by 2030. While greenhouse gas reduction has become a common sustainability benchmark for many companies, Suntory’s holistic approach to sustainability has compelled the company to go beyond its core business in order to protect its most important natural resource, water.

Since 2003, Suntory has engaged in forest cultivation through its Natural Water Sanctuary activities in 21 locations around Japan, cultivating more than twice as much clean groundwater as is used in all its domestically produced products. These initiatives are pursued through the Suntory Institute for Water Science and in collaboration with various experts and stakeholders, including scientists and local governments. Tomomi Fukumoto, Suntory Holdings’ Chief Operating Officer of the Corporate Sustainability Division, explained: “Our basic philosophy of water sustainability is that water is a gift from nature, and we are only making use of a part of the bigger water cycle of the planet. Interfering as little as possible and returning more than we take are key principles.”

TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION, DEPUTY CHIEF SUSTAINABILITY OFFICER

Suntory aims to extend its water management activities across its global footprint, cultivating more water than it uses worldwide by 2050, to help combat water scarcity that is expected to impact nearly 4 billion people around the planet.

Similar to Suntory, Toyota has set a goal of carbon neutrality by 2050 and is investing heavily in the development of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and other technologies that will be key to decarbonizing society. But just as Suntory turned toward forest management as a path toward sustainability, Toyota is increasingly looking beyond its core business of automobiles to the entirety of the built and digital environments. “Since before the COVID-19 pandemic, the automotive industry was already undergoing a once-in-a-century transformation,” explained Yumi Otsuka, the deputy chief sustainability officer at Toyota. This moment of change has compelled Toyota to change its self-image from an “automotive company” to a “mobility company.”

Otsuka’s presentation highlighted one of the results of this new philosophy: the Woven City project, a model city announced at the CES trade show in 2020 and currently under construction in Shizuoka Prefecture near Mount Fuji. This development will feature not only Toyota-manufactured autonomous vehicles, but also sensor-laden buildings and streets and high-tech offices and homes, all sharing data and operating in an integrated manner. Perhaps even more important for Toyota than test-driving its self-driving technology, the city is being designed as a seedbed for collaboration with other technology companies, researchers and citizens to develop solutions to today’s social challenges. “We’ve already received many inquiries from people who want to live or run projects in the city,” Otsuka said.

Envisioning a circular economy

While Toyota and Suntory are industrial conglomerates with business models firmly rooted in producing and selling goods, Mercari has created a platform adopted by nearly 20 million monthly users who have embraced its model of peer-to-peer trading of goods. “We are facilitating a market between individuals,” explained Fumiaki Koizumi, the firm’s director and president. He continued, “We want to create direct, seamless connections … where market inefficiencies existed before technology.”

One of the inspirations for starting Mercari was the founders’ experience traveling around the world, when they were shocked to see so much mass-produced stuff everywhere, both in developed and developing countries. “We realized we need to create a society that reuses instead of throws things away,” Koizumi recalled. Mercari seeks to solve this problem by creating an easy-to-use secondary market where goods can circulate many times before being discarded. This clear vision of a circular society has been at the core of Mercari’s business since its founding, and has helped the company to attract talent from more than 40 countries.

Considering wider society

MERCARI CO., LTD. DIRECTOR, PRESIDENT (CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD) CEO OF KASHIMA ANTLERS F.C. CO., LTD.

All three panelists reiterated the need to think beyond the narrow profit of a single company. For example, in Mercari’s case, a thriving secondary market could end up harming creators if sales of new products declined. Koizumi shared his ambition to “create a system where as things are sold on Mercari two, three or four times, the original creators would receive a payback, similar to a royalty.” Whereas the current economic system encourages creators and manufacturers to earn profit through mass production, a system that rewards makers of long-lasting products over time could increase the profitability of more sustainable business models.

Toyota and Suntory also see their role as part of broader society. As part of its shift toward a mobility company, Toyota has updated its mission to “producing happiness for all.” While this may sound at first like an unexciting slogan, Otsuka explained that under the leadership of President Akio Toyoda, “employees have gradually come to see their jobs as thinking about the happiness of others, and this shift in culture has been solidified during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Likewise, Suntory has long operated according to a philosophy of giving back to society, investing in its sustainability initiatives as well as cultural enterprises such as Suntory Hall.

The panelists’ discussion underscored that regardless of whether a company is a long-standing giant or a young startup, truly incorporating ESG thinking into business strategy starts with corporate culture. As Mercari’s Koizumi summed up his company’s management philosophy, “The important thing is to remember what kind of organization we should be in order to achieve our mission.” As more companies make sustainability a part of their mission, they will need to firmly root their visions in their core values.