December 16, 2021

Over a century of nutrition research and practice

PHOTOS: PUBLIC INTEREST INCORPORATED FOUNDATION, JAPAN ASSOCIATION FOR IMPROVING SCHOOL LUNCH

PHOTOS: THE JAPAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION

The world is facing a new reality where persistent undernutrition and escalating overnutrition coexist even within individual populations. This double burden creates a set of new challenges for policy and program development. With less than five years left to achieve the World Health Assembly’s targets for maternal, infant and young child nutrition, and 10 years to reach the U.N. sustainable development goals (SDGs), the third Nutrition for Growth (N4G) Summit will be held in Tokyo from Tuesday to Wednesday.

The summit aims to foster common understanding of key actions needed to improve nutrition worldwide and to provide a forum for discussions under five themes: integrating nutrition with universal health coverage; building food systems; promoting resilience; promoting data-driven accountability; and ensuring financing for nutrition. Governments, international organizations, the private sector and society will be encouraged to present new funding plans or policy commitments to accelerate the implementation of their initiatives.

As the host and a country with one of the highest life expectancies in the world, Japan is ready to share its expertise accumulated over more than 100 years. The nation’s long dedication to nutrition will provide insights into ending nutrition-related issues and achieving a brighter future for all.

Origin of commitment

Japan’s nutrition initiatives date back to the late 19th century. To tackle nutritional deficiencies caused by food insecurity, Dr. Tadasu Saiki established the world’s first nutrition research institute privately in 1914, which was relaunched in 1920 as the National Institute of Nutrition, predecessor to the National Institute of Health and Nutrition (NIHN). The institute researched the nutrient composition of major food items and the dietary intake per capita as determined by surveys. With this information, the government could take appropriate measures, paving the way for the national nutrition policy of “leave no one behind.”

After World War II, with assistance from abroad, Japan overcame nutritional deficiencies in a short time through nationwide activities led by nutritional specialists. Of particular note was the annual nutrition survey, which began in 1945. Dr. Hidemi Takimoto, chief of the Department of Nutritional Epidemiology and Shokuiku at the NIHN, says the survey shows “the government was aware of the importance of monitoring people’s nutritional status in developing nutrition policy.” Except for 2020 and 2021, when it was suspended due to the coronavirus pandemic, the survey has been conducted annually for over 75 years.

During Japan’s high economic growth spurt from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, the survey was expanded to include blood pressure measurements in response to the rise of new nutrition challenges, such as obesity and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).

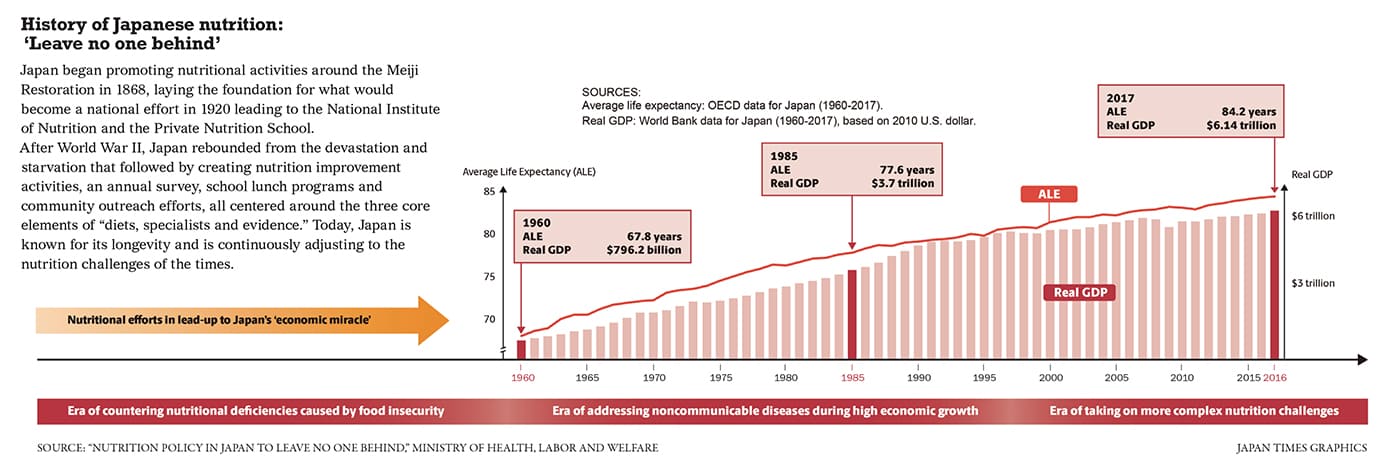

This policy allowed Japan to make substantial gains in both life expectancy and gross domestic product, and in 1985, it reached the highest level of longevity in the world.

Japan began promoting nutritional activities around the Meiji Restoration in 1868, laying the foundation for what would become a national effort in 1920 leading to the National Institute of Nutrition and the Private Nutrition School.

After World War II, Japan rebounded from the devastation and starvation that followed by creating nutrition improvement activities, an annual survey, school lunch programs and community outreach efforts, all centered around the three core elements of “diets, specialists and evidence.” Today, Japan is known for its longevity and is continuously adjusting to the nutrition challenges of the times.

Japan’s nutrition policy

SOURCE: “NUTRITION POLICY IN JAPAN TO LEAVE NO ONE BEHIND,” HEALTH, LABOR AND WELFARE MINISTRY

JAPAN TIMES GRAPHICS

Japan’s health and nutrition policy consists of three main elements: educational activities based on diet; training and deployment of specialists; and a policymaking process based on scientific evidence.

The first element focuses on promoting diet and eating style. The traditional Japanese diet is characterized by ingredient diversity and meals consisting of a staple food, main dish and side dish for nutritional balance. Japanese learn this through school lunch programs, in which they are made to serve lunch to their classmates. They thereby learn about portion size and how various dishes go together.

The second element involves sending trained specialists and volunteers to manage nutrition at facilities nationwide. Their activities play an important role in shokuiku, as food and nutrition education is called in Japan.

Food services provided at schools, company cafeterias and hospitals in Japan are managed by registered dietitians (RDs), who are licensed nationally, and dietitians, who are licensed by prefectures. Japan’s RDs and dietitians are so effective they are now even contributing to dietitian systems in Vietnam and other countries.

The final element is a framework where scientific evidence feeds the decision-making process. Under this framework, the government has formulated initiatives locally and regionally to reduce health disparities across regions. One example is the Smart Life Project, initiated in 2011, which aims to create a society in which everyone, including those who are less health-conscious, can be healthy. It encourages the development of food products that reduce sodium intake and increase vegetable consumption.

On the other hand, shokuiku remains at the core of Japan’s nutrition policy. The government has drawn up a Basic Plan for the Promotion of Shokuiku every five years since 2006, and the fourth plan, which began in March, positions shokuiku as part of Japan’s action plan to contribute to achieving sustainability in line with the SDGs. The plan calls for efforts to promote shokuiku with a focus on lifetime physical and mental health, sustainable food and nutrition, and responses to digitalization.

These developments in Japan’s health and nutrition policy mean the country is entering a new phase and is ready to extend its reach worldwide. Takimoto expressed her hopes for the upcoming N4G summit, saying, “I see this summit as an opportunity to reaffirm the fact that nutrition is fundamental to good health and to take action toward ensuring equal access to safe and nutritious food.” She will speak about child nutrition at one of the side events during N4G.

Global challenges

PHOTOS: HEALTH, LABOR AND WELFARE MINISTRY

The pandemic has damaged food supply chains and delivered an economic blow to households, and the world can no longer delay acting on malnutrition. One bright note, however, is that what the world is facing today is not new to Japan. With vast experience and knowledge accumulated through a century of research, Japan can offer solutions to nutritional challenges and help achieve a caring and resilient society in which no one is left behind.

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 7 article list page