October 25, 2024

The revived tradition and future of matured sake

AGED SAKE

Juku to Kan is a shop and bar specializing in matured sake. At the counter, which seats just five people, you can savor matured sake and dishes that pair well with it, served by bar proprietor and Juku to Kan President Nobuhiro Ueno.

PHOTOS: TAKAO OHTA

Juku to Kan matured sake shop and bar

1F/B1 Sanbancho Building

7-16 Sanbancho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Tel:080-8015-5274

Open: 14:00-20:00. Closed Tuesdays and Wednesdays.

https://sakematured.com/

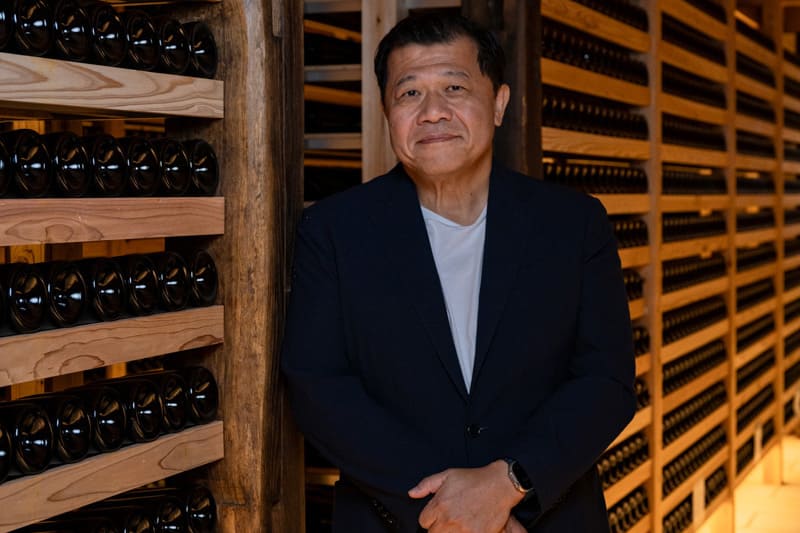

Sake is principally made using a technique called kanzukuri (“cold production”), brewed in winter from painstakingly grown rice, crystal-clear water and cultured kōji yeast and then shipped between January and March. The fresh flavor of cold-produced sake has made it popular as an alcoholic beverage to be savored with meals. However, some people are seeking to spread the word about an entirely different type: matured sake, created by aging sake for long periods in a temperature-controlled environment, much like wine or whisky. One of them is former Boston Consulting Group Japan co-chair Takashi Mitachi, who now serves as representative director and chairman of Juku to Kan, a shop and bar specializing in matured sake.

“Many people are astonished to discover that sake can be aged, but matured sake was perfectly commonplace in the Edo Period (1603-1868) and early Meiji Era (1868-1912),” he said. “As written accounts of this still survive today, we know that the tradition of appreciating matured sake is a venerable one. But changes to the liquor tax law in the middle of the Meiji Era meant that sake was taxed from the moment it was produced, so brewers could no longer afford to leave the drink to age, and the culture of matured sake became obsolete.”

Despite sake’s growing popularity overseas and with inbound tourists, the domestic market is in the doldrums. Net sales have slumped from in excess of ¥1 trillion ($6.8 billion at current rates) in 2000 to around ¥450 million in 2023. It was against this backdrop that Mitachi, who has spent the last 10 years or so addressing the challenge of “value-added sake,” began to focus on the unlimited potential of matured sake.

“While there’s no precise definition of matured sake, we regard it as sake that has been allowed to age over time in an appropriate environment, transforming it into a drink with a complex depth of flavor,” he explained. “There are two ways to make matured sake. One is vintage aging, in which a single type of sake is allowed to age thoroughly. The other involves blending a number of types of matured sake that have been aged for at least five years. Unless the blender knows the differences arising from such factors as the year of production and the original sake types being used, it’s tricky to achieve a balance that will achieve a good outcome. But, done well, it’s possible to produce an appealing matured sake with abundant complexity of flavor.”

Mitachi says the individual character of matured sake results from both the cumulative temperature and the degree of polishing to which the rice is subjected. Sake left to age at 5 degrees Celsius will be completely different from that aged at 15 degrees, even if the aging period is the same, because maturation generally proceeds faster at higher temperatures. As for polishing, the more of the grain that is milled away, the more it loses amino acids and other components, leaving behind pure starch and making bringing out a complex flavor harder. If around 50% to 60% is left, various organic acids develop into a complex flavor. So sake brewed from rice that has not been excessively polished is the most suitable for aging and offers the potential for a more profound umami.

“Each brewery has its own approach to aging,” Mitachi explained. “We’ve also partnered with those that have a clear philosophy around matured sake to produce our own Juku to Kan original matured sake. As the Maillard reaction between sugars and amino acids gradually proceeds, the sake changes from almost completely clear to brown,” much the same way as baking browns breads. “In striking a balance between the degree of polishing and the storage temperature, a number of breweries have techniques for ensuring a pleasant flavor, and some even specialize exclusively in matured sake. I’m working with Juku to Kan President and bar proprietor Nobuhiro Ueno to track down matured sake from breweries of this kind.”

All the glasses used at Juku to Kan’s bar have a rim that curves outward. Whereas wine glasses enable wine to flow over the entire palate, the rim on these glasses channels the matured sake into a narrow stream that gives it a crisper taste, Ueno explained. Into my glass he had poured Daruma Masamune Over 5 Years, a Juku to Kan original. This fine example of assemblage had been created by selecting only outstanding vintages aged for six years from among the numerous varieties of Daruma Masamune matured sake produced by the Gifu brewery Shiraki Tsunesuke. With an excellent balance of umami, sweetness and aroma, it enchants the drinker as it streaks along the palate.

Another interesting way to enjoy matured sake is to try it at different temperatures. Take, for example, Tamagawa Spontaneous Fermentation Junmaishu (Yamahai) “Vintage” 2018, which is produced by the Kinoshita Brewery in Kyotango, a city in the prefecture of Kyoto. It is the result of aging spontaneously fermented junmaishu — pure rice sake — for three years or more. At room temperature, it fills one’s mouth with a nutty fragrance and an umami reminiscent of dashi stock. However, when slightly warmed to around 40 degrees, its body and aroma mellow, enabling the umami to come clearly to the fore. The difference in flavor is so great that one can hardly believe it is the same sake.

Juku to Kan also has an online store, where a team of tasters consisting of Ueno and three other experts provide detailed explanations of each sake’s flavor and ideal serving scenario, such as before, during or after a meal. This makes it simple for even sake novices to choose a bottle. To ensure the appraisals are unbiased, the three other experts are independent of Juku to Kan.

“The world of wine has a well-established culture of reviews and commentaries by expert tasters,” Mitachi said. “One reason why the matured sake market has struggled to grow until now is that this kind of culture hasn’t yet developed. Many people express unease about the fact that one can’t determine the quality of a matured sake until one drinks it, so we post appraisals by several tasters in an effort to establish a culture of reviews and commentaries that will enable people to feel comfortable choosing a bottle.”

Ueno, who formerly ran a bar specializing in matured sake, truly is a professional in this field. He is also executive director of the Toki Sake Association for aged sake, in whose founding he played a central role. Mitachi and Ueno aim to formulate standards for evaluating matured sakes, promote the culture of matured sake and create high added value with a focus on maturation times. Guided by this mission, from a tiny five-seater bar, they are spreading a powerful message about an old yet new sake culture that will gain global currency.

TAKASHI MITACHI

Representative director and chairman, Juku to Kan. Born in 1957. Received his MBA from Harvard Business School as a Baker Scholar. After joining the Boston Consulting Group, he served as the firm’s Japan co-chair from 2005 until 2015, and as a member of its Worldwide Executive Committee between 2006 and 2013. Now focused on the topics of culture and support for the next generation, he currently serves as a director of the Ohara Museum of Art and professor at the Graduate School of Management, Kyoto University, among other positions. In June 2023, he opened Juku to Kan as part of his efforts to spread Japanese culture.

熟成酒の伝統を掘り起こし、日本酒の未来をつくる。

日本酒をワインやウイスキーのように適切な温度管理のもとで長期熟成させ、熟成酒としてまったく別の日本酒文化を広めようとしているのが、元ボストン・コンサルティング・グループ日本代表を務め、現在熟成酒専門の販売店でバーも併設する《熟と燗》代表取締役会長の御立尚資。「江戸時代から明治時代初期頃まで熟成させた日本酒は普通に流通していました。明治中期に酒税法が変わり製造された瞬間から税金がかかるようになったため、熟成日本酒の文化が廃れていきました」と語る。

海外やインバウンド旅行者の間で人気が高まっている日本酒だが、国内市場は低迷している。2000年には1兆円余あった売り上げは2023年には約4500億円までに落ち込む。そのような中で10年ほど前から“付加価値のある日本酒”という課題に取り組んできた御立は、熟成酒の持つ無限のポテンシャルに注目する。

「熟成酒の作り方には二つの方法があります。日本酒1種類をじっくり熟成させるビンテージ熟成と、5年以上の熟成酒をいくつかブレンドして作るものです」。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 41 article list page