May 31, 2024

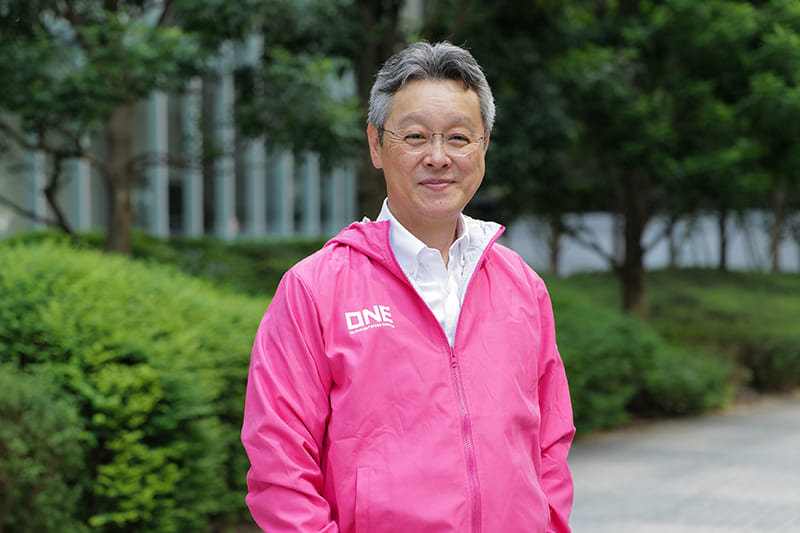

PRI’s Morisawa discusses Japan institutional investors

As the world struggles to curb global warming and other threats to the environment and society, what role should Japanese institutional investors play?

What they need to do, says Michiyo Morisawa, the Japan senior lead of the global network Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), is to build up more knowledge and analytical capacity to support investee companies’ long-term sustainable business strategies.

European institutional investors have gained a high reputation among top Japanese managers for their expertise on making good suggestions for businesses’ futures. The United Nations-supported PRI was launched in 2006 to encourage institutional investors to incorporate ESG (environmental, social and governance) factors into their investment decisions.

In recent years, companies have faced increasing pressure to disclose information about the risks and opportunities of how environmental and social issues influence their businesses, while institutional investors have come to feel more responsible to help support a sustainable society.

Asked what Japanese investors can do to create effective dialogues with their investees, Morisawa said, “The first thing they must do is to expand their knowledge.” The ultimate purpose of such engagement between institutional investors and companies is to raise corporate values in the long run. “Those who promote engagement need to have the ability to analyze the companies and make suggestions,” Morisawa said in the recent interview, part of a monthly series by Naonori Kimura, a partner for the consulting firm Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI).

“What asset owners think decides their course of action in the capital markets, as they are positioned in the upstream of investment chains,” Morisawa said. Asset owners, based on their fiduciary duty to act in the best interest of their beneficiaries, give investment directions to asset management companies, which determine where the money is invested. This means asset owners’ investment policies strongly affect asset managers, she said.

It would be ideal if asset owners set up clear policies or frameworks and showed them to asset management firms. Also, a set of rules like the EU’s taxonomy system for sustainable finance would be useful, she said. The European Commission says the EU taxonomy, launched in 2020, helps companies and investors identify “environmentally sustainable” economic activities and make investment decisions accordingly.

Morisawa said the global investment landscape has changed drastically in the past decade, with an approach that takes ESG issues into account coming to permeate the financial markets.

Since PRI was established, more than 5,300 institutions around the world have signed the framework aiming to promote investments with a long-term perspective. As a result, there is a global consensus in the business world to protect the environment and natural and human resources.

In Japan, the Financial Services Agency set up the Stewardship Code, based on the U.K. Stewardship Code, in 2014 to encourage constructive dialogue between investors and investees for sustainable corporate growth. The following year, the Tokyo Stock Exchange created its Corporate Governance Code, requiring companies to make fair and transparent decisions for all kinds of stakeholders — including shareholders, customers, employees and local communities. Those listed on the Prime market are now required to prepare disclosures in English for overseas investors.

Also, the 17 sustainable development goals adopted by the United Nations in 2015 and the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change have affected the progress of the global consensus on ESG issues, Morisawa said.

However, Japanese institutional investors need to catch up with their Western counterparts, she said. “Although more than 5,300 institutions are PRI signatories, about 4,000 of them are those in Europe and North America,” Morisawa said, and the number in Japan is a mere 120 or so. “Among Japanese asset owners, many insurance companies signed the PRI, but few public pension funds did. There is a gap between how the Japanese government has committed itself to carbon neutrality and how the public pension funds act.”

Japan’s commitment dates to 2020, when then-Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga pledged in his first policy speech that the country aimed to cut greenhouse gases to zero by 2050 and become a carbon-neutral society.

Since the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), the nation’s largest public fund investor by assets, became the first Japanese institution to sign the PRI in 2015, it has proactively worked on ESG-related investments. But few other pension funds followed suit. Hoping to speed up this slow progress, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida last October told the annual global conference PRI in Person that at least seven Japanese pension funds managing as much as ¥90 trillion ($580 billion) would join the initiative. In March, one of the pension funds, the Federation of National Public Service Personnel Mutual Aid Associations, signed the PRI.

Kishida’s pledge is part of the government’s plan to encourage a larger portion of the nation’s household financial assets, worth more than ¥2 quadrillion, to be channeled into investments, which would benefit both corporate growth and households themselves. Other parts of the plan include widening the Nippon Individual Savings Account (NISA) program, a new type of tax exemption for small investments, reforming asset management businesses and encouraging good corporate governance.

Investees’ ESG-related disclosures have progressed in the last decade. Last year, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), a global body for setting disclosure standards, published the final version of its standards, addressing the issue that global companies’ disclosures had been based on many different standards. Based on these new standards, the Sustainability Standards Board of Japan (SSBJ) plans to finalize the Japanese version by the end of this business year next March.

Morisawa said one problem is that a large number of small-capitalization firms listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange are not yet ready for sustainability-related disclosures. Many global companies have been able to figure out how much carbon they emit and how and where to reduce it, based on data gathered scientifically. “But in the case of companies that are not able to do so, what they should do first is to identify the emissions and disclose the data,” she said.

Such smaller firms also have issues of transparency, Morisawa pointed out.

Some of them have cross-shareholdings to protect themselves from activist investors. But it is important, she said, to unwind these holdings in order to improve their market transparency as well as their management. “They have to work on disclosure, taking into account what they must do to attract investors who can become their long-term supporters,” she said.

Also, some companies outsource their production and have a wide range of suppliers, like Apple, which makes it hard to figure out their overall emissions. They need to prompt their suppliers to identify and disclose their carbon emissions and then make plans for reducing them, she said.

In rural areas, not only megabanks but local banks and shinkin credit banks have expertise in regional businesses and therefore through their investments and lending should be able to play a role in encouraging local companies to reduce carbon emissions, shift to renewables and update manufacturing facilities, she said: “It is time for them to work for their local communities.”