April 30, 2021

Reliving 1964 Tokyo Olympics

SPORTS JOURNALIST

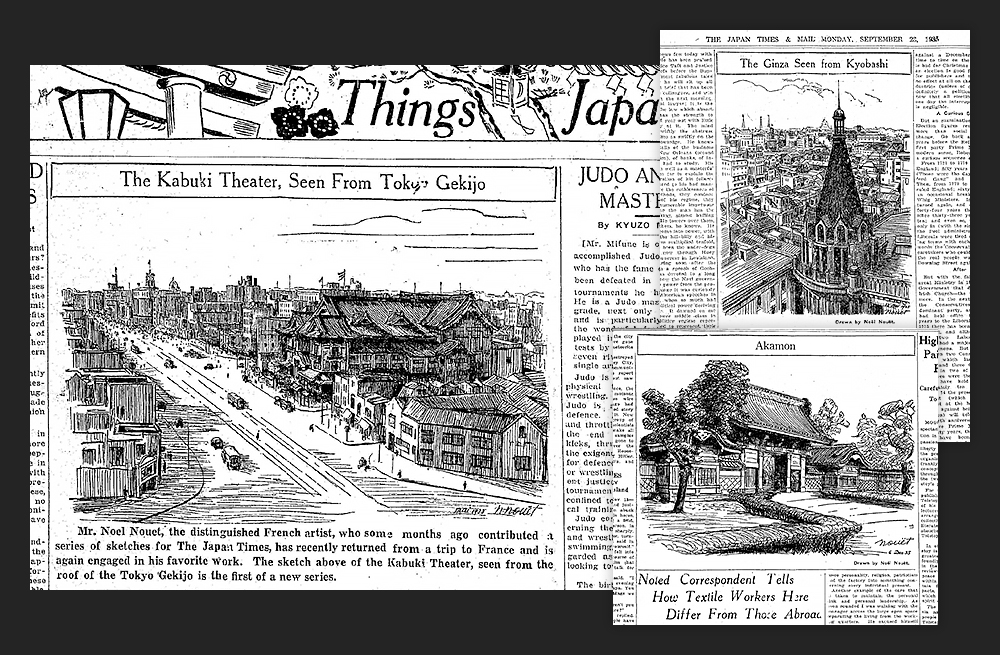

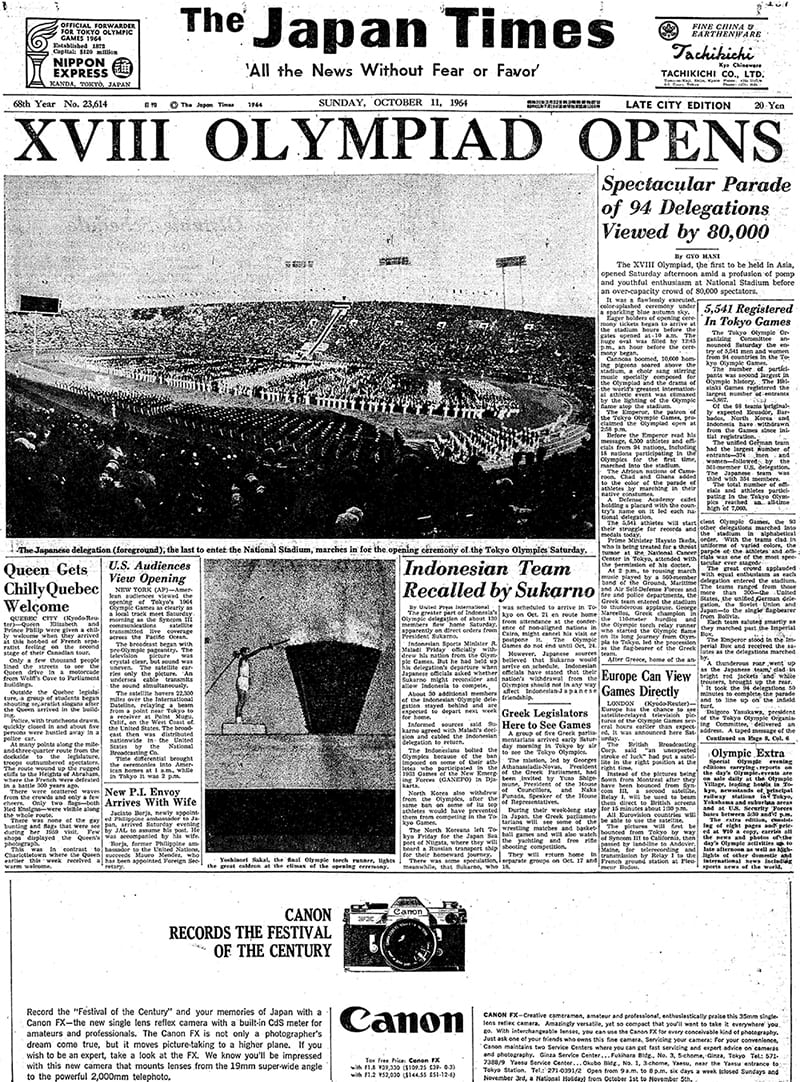

Oct. 23, 1964: The Olympic day that redefined Japan

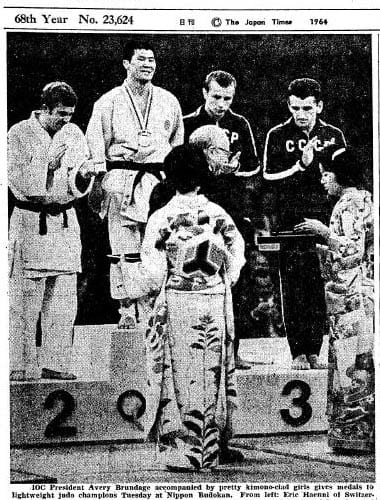

President Avery Brundage, accompanied by kimono-clad girls, gives medals to lightweight judo champions at the Nippon Budokan.

From left: Eric Haenni of Switzerland, silver; Takehide Nakatani of Japan, gold; and Soviets Oleg Stepanov and Aron Bogolubov, bronze.

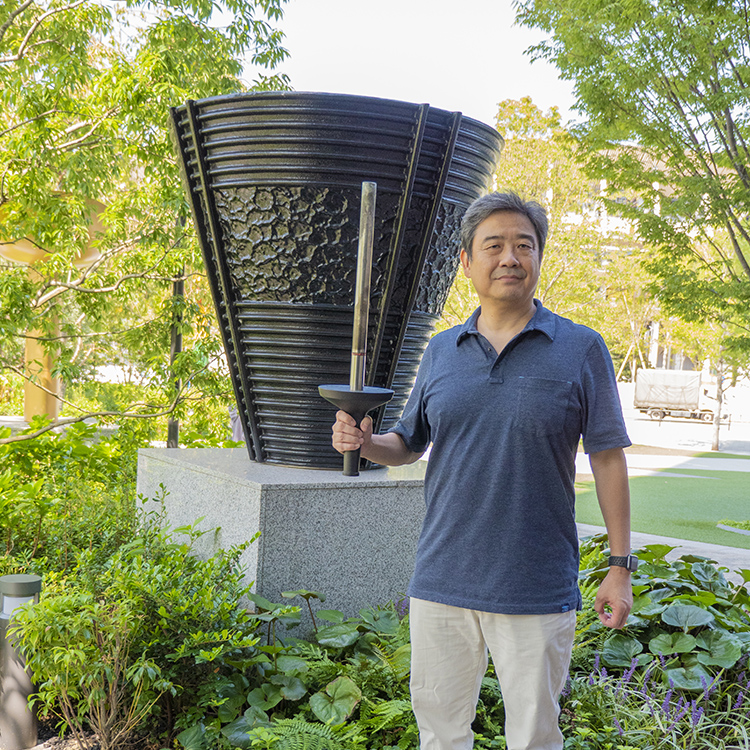

bottom: The New National Stadium, designed by Kengo Kuma, was completed on Nov. 30, 2019.

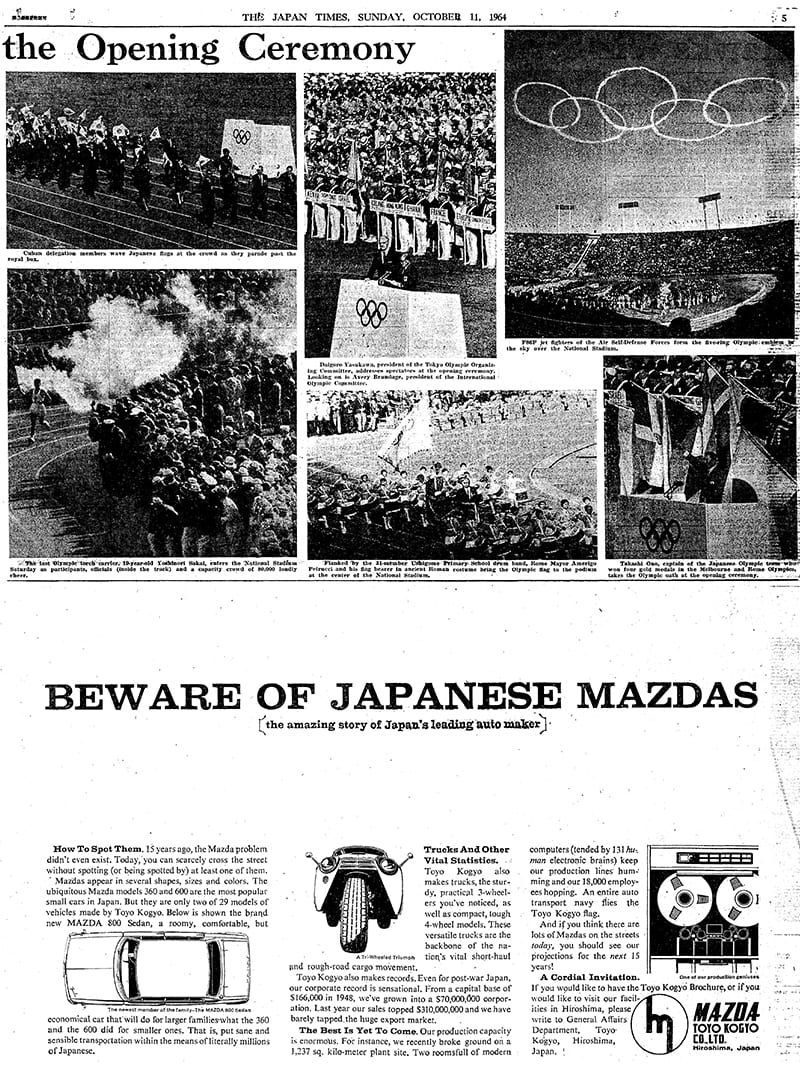

He climbed the steps with the Olympic torch in his right hand, the torch’s base at shoulder height and the cylinder sparking reddish-white and spewing smoke. Twenty steps. Forty steps. Sixty steps.

Yoshinori Sakai held an even pace as he jogged up the stairway to the top of the National Stadium. A hundred forty steps. A hundred sixty steps.

And finally, after climbing the equivalent of an eight-story building, with nary a slip or stumble, Sakai stood next to a large black cauldron, faced the crowd and cracked a huge smile.

Was it relief at making it to the top without a spill? Was it exhilaration upon seeing the field filled with over 5,000 athletes from 93 nations and the stadium with over 70,000 cheering spectators, including the emperor of Japan?

Certainly, those were two of the many feelings all of Japan felt that beautiful autumn afternoon on Oct. 10, 1964, when Japan welcomed the world to the XVIII Olympiad.

Sakai, who was born in Hiroshima on the day the atomic bomb was dropped, had just done what Japan had done: symbolically climbed a mountain.

Regaining confidence

At the end of World War II, Japan had been a defeated, occupied nation in ruins. And yet, in only 19 years, the nation recovered its economy, its standing in the world and its confidence so quickly that it could pull off the most logistically complex peacetime global event at the time, the Summer Olympics.

Memories of poverty, disease and despair were still fresh in the minds of Japanese adults. With great anticipation they worked hard to organize the games, transform the city and ensure a warm welcome for their guests from far and wide. With great concern they worried they would be revealed as a people who could not compete with the rest of the world.

That trying ambivalence bubbled to the surface on the penultimate day of the Tokyo Olympics.

Resignation in the air

It was Friday, Oct. 23, 1964. The Nippon Budokan was packed. But resignation wafted in the air of this newly constructed arena of the martial arts.

Even though Japanese judoka Takehide Nakatani, Isao Okano and Isao Inokuma had already taken gold in the first three weight classes the previous three days, there was considerable doubt that Japanese champion Akio Kaminaga could defeat Dutchman Anton Geesink in the open category.

After all, Geesink had shocked the judo world by becoming the first non-Japanese to win the world championships in 1961. More relevantly, Geesink had already defeated Kaminaga in a preliminary bout. So while the Japanese in the Budokan, including Crown Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko, were hoping Kaminaga would exceed expectations, all they had to do was see the two judoka stand next to each other to worry — the 2-meter-tall, 120-kg Dutch giant versus the 1.8-meter, 102-kg Japanese.

Even though judo purists say skill, balance and coordination are more important to winning than size, deep down many Japanese likely felt that the bigger, stronger foreigner was going to win. After all, the bigger,stronger Allied soldiers had defeated Japan in the Pacific War.

And so Geesink did, defeating Kaminaga handily, sending the nation into a funk.

Two-time Olympic swimmer Ada Kok, invited to the match after winning a silver medal for the Dutch team, was a witness. “I realized I was watching a culture shock of sorts, going throughout Japan,” she said. “The Budokan was silent. Quiet. I could hear people crying.”

The ‘Witches of the Orient’

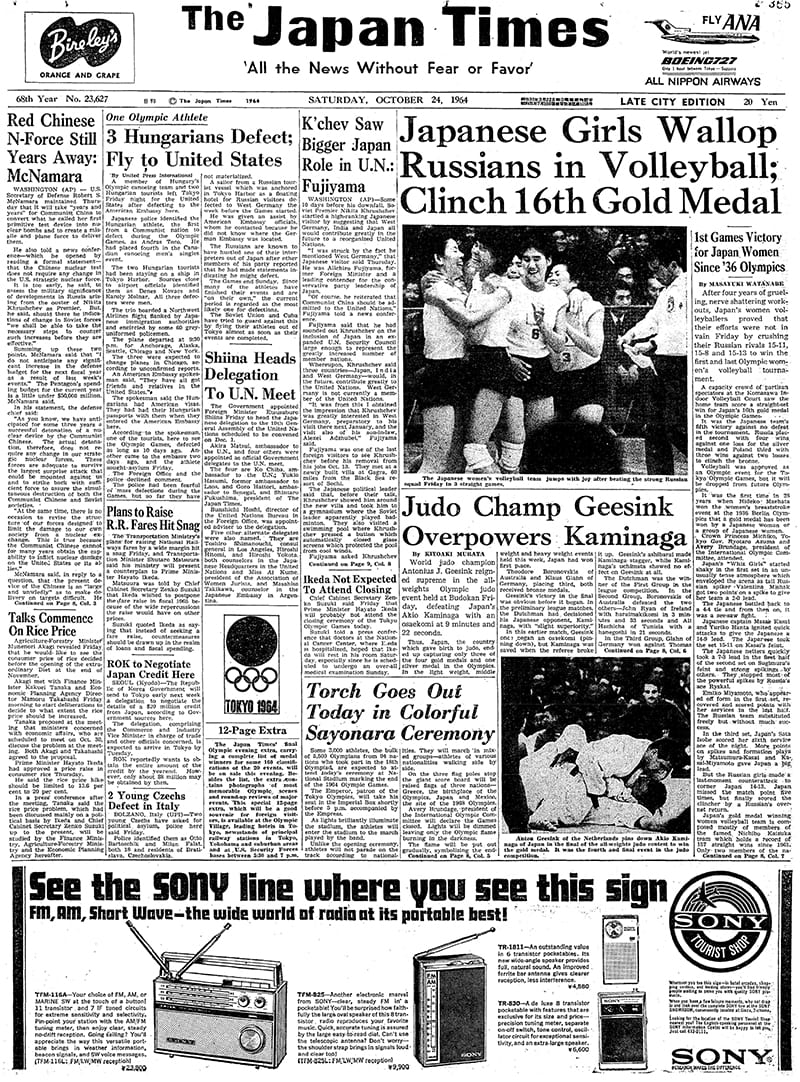

That was late in the afternoon. About 13 kilometers to the southwest, the Japanese women’s volleyball team was preparing for their finals at the Komazawa Indoor Ball Sports Field. They too were going up against bigger, stronger adversaries: the USSR.

This time, though, there was a sense that Japan could defeat the Soviets — they had previously done so at the world championships in 1962 in Moscow. So when nearly every citizen in Japan had settled in front of their television at 7 p.m., with nearly every channel carrying the match, the entire country was in extreme anticipation.

Geesink had just sunk Kaminaga, as well as Japan’s hopes of sweeping gold in the only Olympic sport native to Japan. “Maybe we just aren’t big enough or strong enough,” many may have thought.

Hirobumi Daimatsu, coach of the women’s volleyball team, had worked over the years to train his players to compensate for a relative lack of size and strength through speed, technique and guts.

And much to the relief of the Japanese nation, the famed “Witches of the Orient” defeated the Soviet Union in straight sets: 15-11, 15-8 and, in a tantalizingly close finalset, 15-13.

The team of diminutive Japanese, taking down the larger Soviet women, showed the world they were from a nation to be recognized and respected. Whatever sting lingered from Kaminaga’s loss, whatever shame from the wartime defeat — all negativity evaporated the moment the ball fell to the ground in the match’s final point. A nation lept in unison.

Rock bottom to soaring peak

When looking back on 1964, a monumental milestone in the history of Japan, you must also look farther back to the start of Japan’s arduous journey. Without the rock bottom of 1945, there is no soaring peak of 1964.

And on Oct. 23, 1964, there was no moment more euphoric than the day the Japanese women’s volleyball team carried a nation to the top of the highest mountain.

On that day, Japan was a nation reborn — young and confident — celebrated by the world.

New games, new stadium

Two athletes look to the Tokyo Games

PAULA PARETO

JUDOKA

JUDOKA

My experiences at the 2008 Beijing Olympics were accompanied by feelings of uncertainty. It was my first time participating in such a big competition — everything was new and surprising. Being surrounded by the best athletes in the world made me feel ecstatic, and I told myself I would enjoy it as much as possible. I won the bronze medal — the first medal my country won in the Beijing Games, and Argentina’s very first judo medal ever.

I had more experience by the time I competed at the 2016 Rio Olympics, and managed to achieve the gold medal. That was proof that if you work hard, you can achieve your dreams.

Getting ready for the Tokyo Olympic Games is a little bit different, as we cannot prepare and train as usual; limited contact with people and constant monitoring are the new normal, but we are working on getting special permission to go to Europe, as it is very important for us to train with athletes from different backgrounds. I have great expectations for the Tokyo Olympics,and I will bring my best to this competition.

ASUKA TERADA

100-METERS HURDLES ATHLETE

100-METERS HURDLES ATHLETE

I am looking forward to participating in the Tokyo Olympics not only as a 100-meter hurdles athlete, but also as a mother.

In 2009, I took part in the World Athletics Championship. In 2013, I retired after sustaining an injury. The following year I got married, went to university and gave birth to my daughter.

Since I really wanted to participate in the Olympics held in Tokyo, I returned as a rugby player in 2016. I was lucky to play on the Japanese team for a few months before I broke my leg and had to quit.

Despite that, I decided to return to the world of athletics in 2019. I set a new Japanese record in the 100-meter hurdles and participated in the World Championships for the first time in 10 years.

In Japan, it is common for female athletes to retire after marriage or giving birth, so there are very few active female athletes who are also mothers. For me, staying active is also a way to break away from this stereotype.

My goal for the Tokyo Olympics is to make it to the finals and show my daughter my efforts and accomplishments as an athlete.