March 25, 2022

Japanese fabric: Repeatedly reborn

FABRIC

An item of clothing was worn for so long that only rags and tatters remained — this was the norm in Japan until around 100 to 150 years ago. There were many secondhand clothing merchants in cities and towns. Stained, torn and frayed garments were mended or embroidered and reused, and used clothing was transported all over Japan on trading ships, along with sake and processed goods.

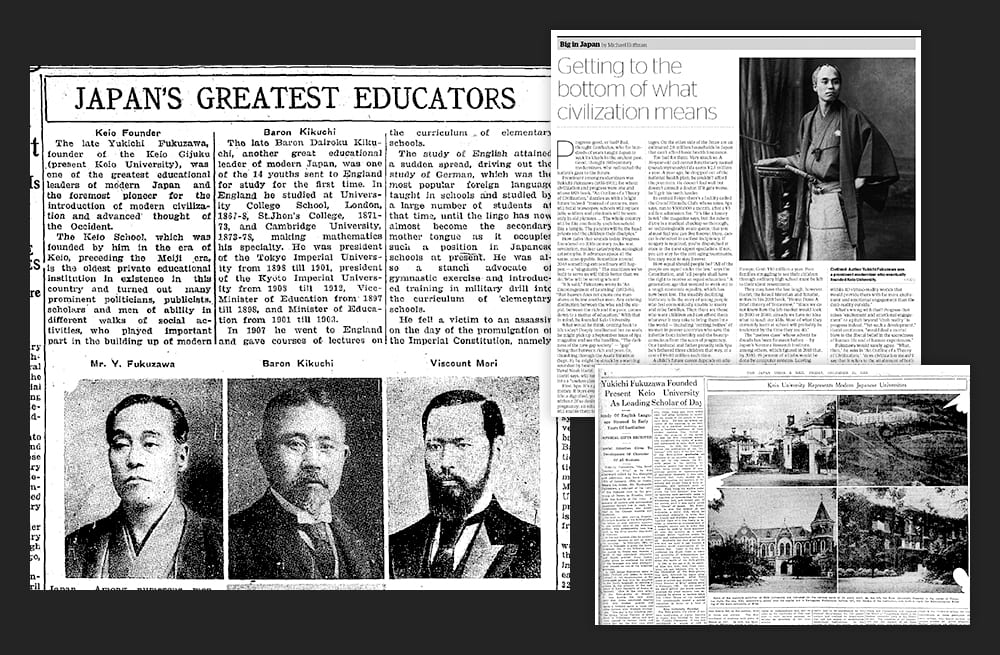

Yoshida’s collection includes this item of work clothing, said to have been used in Fukui Prefecture at the end of the Meiji Period (early 20th century). The garment was woven using hemp waste, called okuso. Hand stitching can be seen in the collar. | PHOTO: ASATO SAKAMOTO

Why was clothing so treasured? Since ancient times, Japan had a culture of spinning thread and making fabric from plants such as hemp and ramie. Because these processes took a great deal of time and labor, most common people had a small number of garments that they wore over and over in rotation throughout the year.

“In preindustrial times, all clothes were made with natural materials, so nearly all were recycled. It seems that until around the Edo Period there was hardly any waste, since items that were no longer usable could be burned as fuel for keeping warm.”

So says Shinichiro Yoshida, artist and director of the Early Modern Asafu (Hemp Cloth) Laboratory, whose fascination with ancient handcrafted cloth has led him to acquire an extensive collection of old clothing and fabric.

Yoshida said: “For ordinary people, fabric was a precious commodity, so there was a tradition of sewing together small pieces of worn and tattered fabric to create a sort of patchwork. In some cases over 100 types of fabric were made into a single garment, or scraps of precious silk were sewn together to make bedding. This clothing, permeated with the wisdom and ingenuity of people meeting the needs of daily life, is amazingly beautiful even today.”

In the 16th and 17th centuries in Japan, cotton cultivation became more widespread and cotton production flourished. But in Tohoku and other cold regions that were not suited to cotton cultivation, unique cultures of clothing reuse developed. Representative examples include Nanbu saki-ori, a traditional craft of southern Aomori Prefecture in which old, worn fabric is torn into thin strips that are woven to create garments and household items. Another example is clothing made from used washi paper. One item in Yoshida’s collection is an undergarment made from used paper with written text, torn up and spun into filaments that are then knitted in a tortoiseshell pattern. It seems that wearing this garment under a kimono in summer served to keep perspiration off of the kimono.

“In 1994, the exhibition ‘Riches from Rags,’ which was based on my collection, was held at the San Francisco Craft Folk Art Museum,” Yoshida said. “It focused on the theme of sustainability and featured boro nuno,” old cloth and garments that have been mended and patched. “I still receive questions from people from overseas who’ve seen the exhibition catalogue. They often ask me who made the items, but in most cases the makers were (anonymous) women living in rural areas. I think repeated trial and error in working with small boro cloth remnants led to the development of various ideas and the cultivation of a rich store of wisdom and techniques.”

That wisdom has been handed down to the present. The project Around, created by design director Reiko Takimoto and flower designer Mikako Ichimura, remakes disassembled old clothing into dresses and other Western-style garments, and suggests styles of wearing the clothing that are suited to modern lifestyles. It may be that many ideas for using a single piece of cloth with care and respect are lying dormant in people’s lives today.

何度も再生を繰り返す日本の布文化

1枚の衣服を小さなボロ切れになるまで使い続ける。戦前まではそれが日本の当たり前だった。都市部には多くの古着商が存在し、破れた服はほつれを直し、刺繍を施すなどして再利用されたという。

古い衣服や布をコレクションしてきた近世麻布研究所・所長で美術家の吉田真一郎に話を聞いた。「古くから日本では大麻や苧麻などの植物から糸を紡ぎ、布に仕上げていく文化がありました。しかし、それらは相当の手間と時間を要するもの。庶民にとって布はとても貴重だったため、ぼろぼろになった布を縫い合わせ、多い時には100種類以上の布を1枚に仕立てるような風習もありました」。吉田のコレクションには、文字の書かれた使用済みの和紙を裂いて細く糸状に紡ぎ、亀甲状に編み込んだ「紙の下着」や、大麻の屑を利用して織られた仕事着などがある。「その作り手の多くは当時の農村部にいた女性たちです。小さなボロ布を前に試行錯誤を重ねるなど、そうした生活者の知恵が詰まった衣服は、いまも目を見張る美しさがあります」。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 10 article list page