June 28, 2021

Sustainable fashion born of fermentation: The renaissance of Awa ai, a traditional Tokushima craft

Page 3

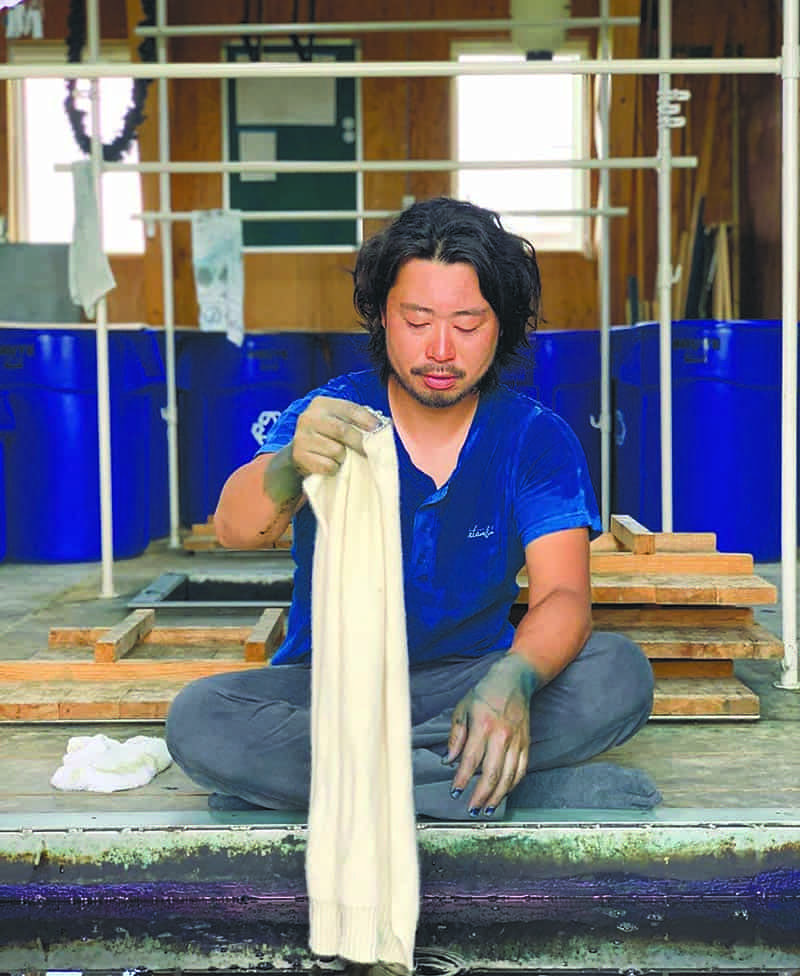

They even grow their own indigo. Harvesting the plants turns the hands bright blue.

PHOTO: WATANABE’S

Japan, with its four distinct seasons, has seen the development of techniques for year-round use of plants harvested in summer and autumn — not only for food, but also for making textiles and clothing. The dye Awa ai, an important traditional Tokushima Prefecture craft named for the feudal Awa clan, is produced with a unique method in which indigo plants harvested in summer are transformed into clothing dye through long fermentation.

PHOTO: WATANABE’S

While indigo dyeing cultures exist around the world, many in hot, humid regions such as India cultivate the plants throughout the year and produce the dye in a process that takes about 10 days. In contrast, the process of making Awa ai involves long fermentation, taking a full year.

Kenta Watanabe of the company Watanabe’s, which is newly spreading the word about Awa ai, is one of those who became enthralled by this culture of fermentation.

“I used to work in the middle of Tokyo. One day I went to an indigo dyeing workshop, and seeing my own hands dyed bright blue sent a shock wave through me. I decided this was what I had to do. So about 10 years ago, I knocked on the door of an aishi (indigo artisan) who makes Awa ai in Tokushima.”

Watanabe says he was particularly interested in how fermentation is used in the production process.

“After drying the indigo leaves that are picked in summer, we first make what’s called sukumo — the basic dye material. Then we spread the leaves on a dirt floor, sprinkle them with water and aerate them, and start the heat fermentation process. This is repeated more than 20 times over a four-month period, to concentrate the color. We’re working with indigo all year round. If you produce good leaves, you can see the difference in the color. Every day there’s something to enjoy.”

Awa ai is the result of this long process — but the number of people practicing the technique of making sukumo from fermented natural indigo has decreased year by year. It is said that at one point there were only five such enterprises in all of Tokushima Prefecture. Currently just two places in the prefecture carry out the entire process from making sukumo to dyeing fabric to producing and selling clothing: Watanabe’s and the brand Buaisou.

“Currently our company does every part of the clothing production process, from cultivating indigo leaves and processing them to make sukumo … to dyeing, to making and selling clothes, so we can avoid unnecessary costs and sell our products at reasonable prices,” Watanabe said. “Right now I feel like there’s a perfect balance between our production scale and our brand’s philosophy. Over the past few years, there’s also been a shift in thinking, and I have a strong feeling that more consumers are interested in brands like ours that take a sustainable approach.”

PHOTO: WATANABE’S

While the fashion industry has long produced huge amounts of clothing for each season, more people have been calling for a re-evaluation toward sustainable practices. The reasonably scaled production process that Watanabe describes may also be a good fit with the world of fermentation, which cannot be controlled by human hands alone. “I feel that I’m always engaging with non-human things, like invisible bacteria and plants,” he said. “All that humans can do is make preparations and create the right setting. Understanding the natural environment is the key factor in continuing to make things of quality.”

発酵から生まれるサスティナブルな「阿波藍」。

徳島県を代表する伝統工芸「阿波藍」は、夏に採取された藍を長期間発酵させて染料に仕上げる独自の染め文化だ。世界中に藍染め文化は存在するが、多くはインド藍などのように高温多湿な国で藍を年中栽培して10日程度で染料にする。一方、阿波藍は二度にわたる発酵を重ねて、丸1年をかけて染料をつくりだす。阿波藍ブランドを発信する「Watanabe’s」の渡邊健太氏は、この発酵文化に魅せられた一人だ。

天然藍を発酵させた「すくも」をつくる技術の担い手は年々減少しているが、この「すくも」づくりから染色、衣服の生産と販売までを一貫して行うのが渡邉氏のブランドだ。

「自社で生産した商品を直接クライアント企業や消費者に届けることができるので、無駄なコストをかけず適正価格で販売できる。また自分たちが無理をしない程度の生産量を保つことは、土地の環境保全にもつながります。生産規模とブランドの持つ価値観とのバランスが、いまちょうど合っていると感じますね」。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 1 article list page