July 29, 2022

The current state of plastic pollution in seas

PLASTIC WASTE

Plastic waste entering the sea is now seen as a critical global problem. The amount already in the sea is thought to total 150 million tons, with 8 million more added every year. It is predicted that the weight of marine plastic waste will exceed that of marine life soon after 2050.

Marine waste was first identified as a problem in the 1970s, but it only started to be mentioned in international political circles at the Group of Seven summit in Elmau, Germany, in 2015. Four years later, at the 2019 Group of 20 summit, a goal was established to stop the addition of any more plastic waste by 2030.

So what is the current situation with ocean plastic waste? We spoke with Yutaka Michida, a professor at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute (AORI) within the University of Tokyo, and Haruyuki Kinoshita of the Institute of Industrial Science (IIS) at the University of Tokyo. Both are working on a joint research project, FSI Marine Plastics Research, being conducted by the University of Tokyo and the Nippon Foundation.

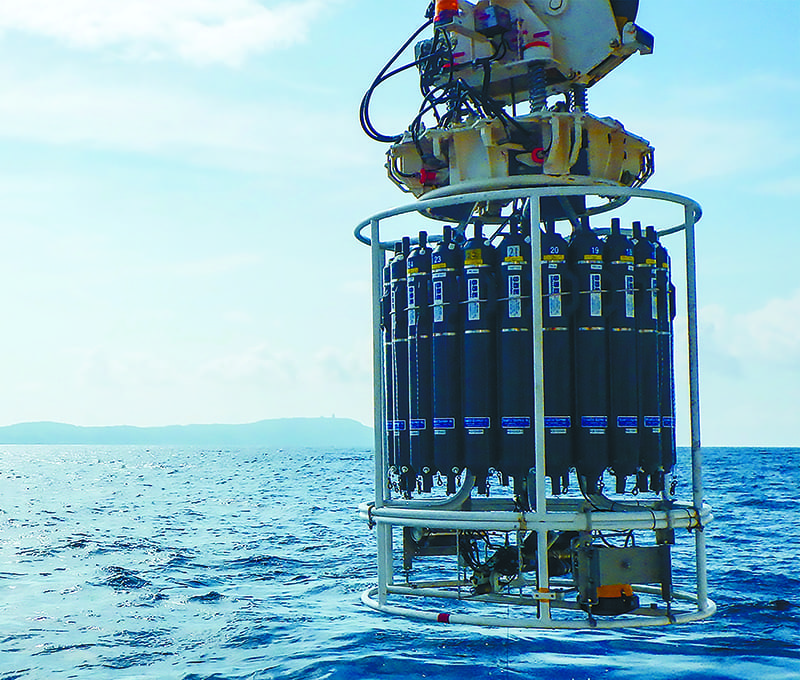

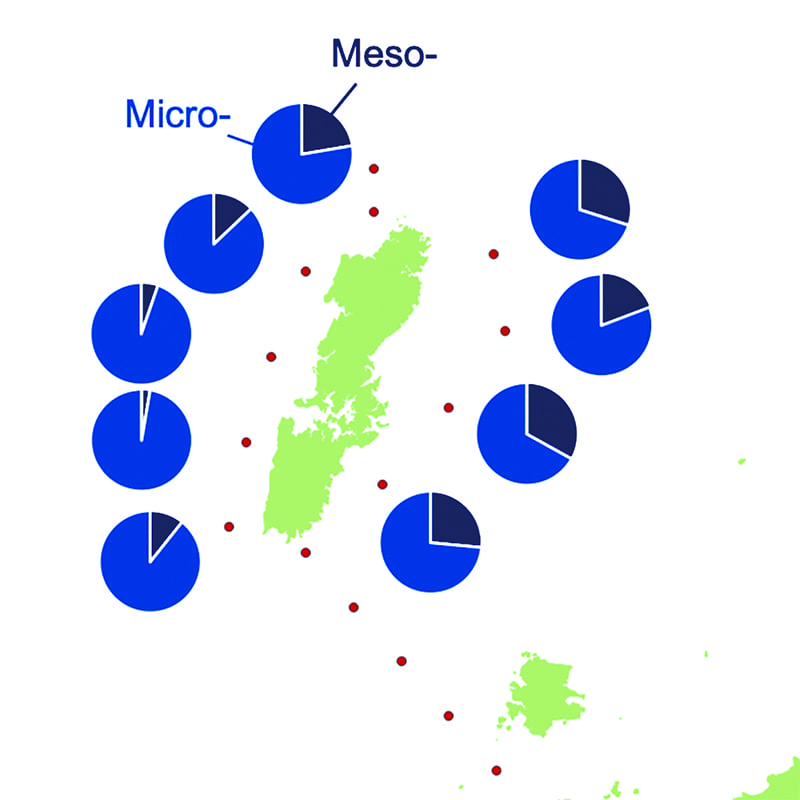

“In a survey to help us understand the current situation, we investigated the plastic density in seawater samples taken over the past 70 years [1949-2016] by Japanese fisheries research and educational institutes, and found that the volume of plastic waste has been increasing tenfold every decade,” Michida said. “Meanwhile, recent research has shown that the smaller the plastic particles, the more likely they are to accumulate in the mud on the seabed. Further, it has become clear that the size and type of plastic will influence its distribution by ocean currents and also the time it takes to accumulate within living organisms. This knowledge will potentially help us develop plastics with less environmental impact in the future.”

With his colleagues, Michida is also investigating the effects of ocean plastics on marine life and the human body.

“When we examined hermit crabs that lived in coastal areas where plastic pollution was advanced, we found that in addition to microplastics, chemical substances added during the plastic manufacturing process had also accumulated inside them. Those substances may also be harmful to the crabs’ metabolism,” he said. “We also investigated the effect of microplastics on the human body. After conducting experiments using cultured cells, we discovered that fine particles of tens to hundreds of nanometers in size can enter the human bloodstream and lymph nodes. As a result, it is highly possible that humans will also absorb microplastics, and harmful substances will accumulate inside their bodies.”

So all sorts of problems are connected with ocean plastics. But perhaps the most important task now is to raise awareness in order to reduce the amount of waste that is generated in the first place. Kinoshita, who is working on an oceanographic data research platform, OMNI, that involves the participation of local residents, explained.

“The efforts of researchers alone will never be enough, so we are trying to build a mechanism to collect data [on microplastics] with the help of citizens,” he said. “Recently, we have collaborated with Zushi city [in Kanagawa Prefecture] to collect beach sand with local children, and we are now developing a program that will calculate the total amount of microplastics found in those samples. These educational activities are greatly appreciated by the Zushi citizens, who tend to be environmentally conscious. On the other hand, in places like Tsushima in Nagasaki Prefecture, the situation is different, because instead of household waste we find a great deal of industrial waste that is washed there from other countries. The opinions and ideas of the locals will differ by location, so it is important to hear from them directly.”

Currently the project is entering its second phase, and plans are afoot for further collaboration with local science groups, local governments and citizens to raise awareness. When it comes to keeping plastics out of the ocean, it seems there is still much more that needs to be done.

海洋プラスチックゴミを取り巻く世界の現状。

現在、海中に存在するプラスチックは1億5千万トン、2050年以降には魚の重量を超えるという予測も出ている。東京大学と日本財団による共同研究「FSI海洋プラスチック研究」を進める、東京大学の道田豊氏、木下晴之氏に話を聞いた。「国内だけでも10年で10倍単位の海洋プラスチック汚染が進行していることが調査で判明しました。また海洋生物の体内に化学物質が蓄積したり、人間も有害物質を溜め込んでしまったりする可能性は大いにあります」と豊田氏は語る。

市民参加型の海洋データ調査プラットフォームOMNIを推進する木下氏は次のように語る。「研究者たちの収集や調査だけでは到底追いつきませんので、市民の方たちとデータを収集する仕組みを構築しています。最近では逗子市とも連携し、地元の子どもたちと砂浜からマイクロプラスチックを調査するプログラムを展開するなど、各地域固有の声やアイデアを市民の方々から集めていくことも重要です。今後はいっそうの自治体との連携や市民参加による社会普及を目指していきます」。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 14 article list page