August 26, 2022

How Ban’s disaster relief projects have evolved

PARTITION

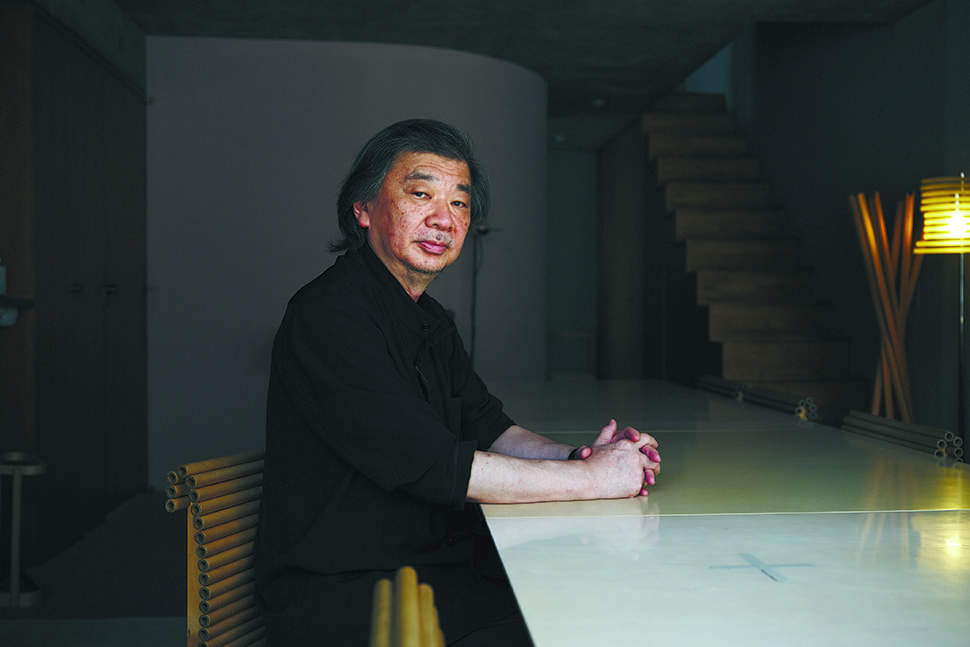

The Great Hanshin Earthquake (also called the Kobe earthquake) struck on Jan. 17, 1995. Architect Shigeru Ban’s volunteer support work for disaster victims in Japan began at that time.

“Even though they weren’t buildings that I designed,” Ban said, “as an architect I felt a certain responsibility for the fact that many lives were lost because of architecture and construction.” At the end of that January, Ban visited Takatori Church, which was located in the stricken area. Many Vietnamese refugees had gathered there. Ban presented a proposal for replacing the church structure, which had been destroyed by fire, with a temporary building made from paper tubes. Through discussions with the church, the decision was made to build a temporary community center that could be used by area residents and serve as a place to hold Sunday Mass. As it turned out, it was Ban who gathered donations to fund construction costs and recruited volunteers to do the construction work.

The project eventually evolved into Paper Log House, a group of temporary homes for Vietnamese refugees who were still living in tents in parks. The Paper Church and 30 of the houses were completed by September 1995. When its original role came to an end in 2005, the Paper Church was relocated to central Taiwan and used as a permanent community center in the Nantou County village of Taomi, which had been devastated by an earthquake.

In 1996, Ban founded the NGO Voluntary Architects’ Network (VAN) to provide support for disaster-stricken areas and displaced people. With the cooperation of his own design company and Shigeru Ban Lab at Keio University’s Shonan Fujisawa Campus, VAN created a system for carrying out volunteer activities on a continuous basis.

Ban said, “It may be an NGO, but there’s actually only one full-time staff member besides me. While VAN does have a role as a receiving entity for public subsidies from the government and so on, it takes time for public funds to be issued, and there are a lot of constraints. To quickly launch a project in a disaster-stricken area, it’s also important to raise project funds on your own to the greatest extent possible.”

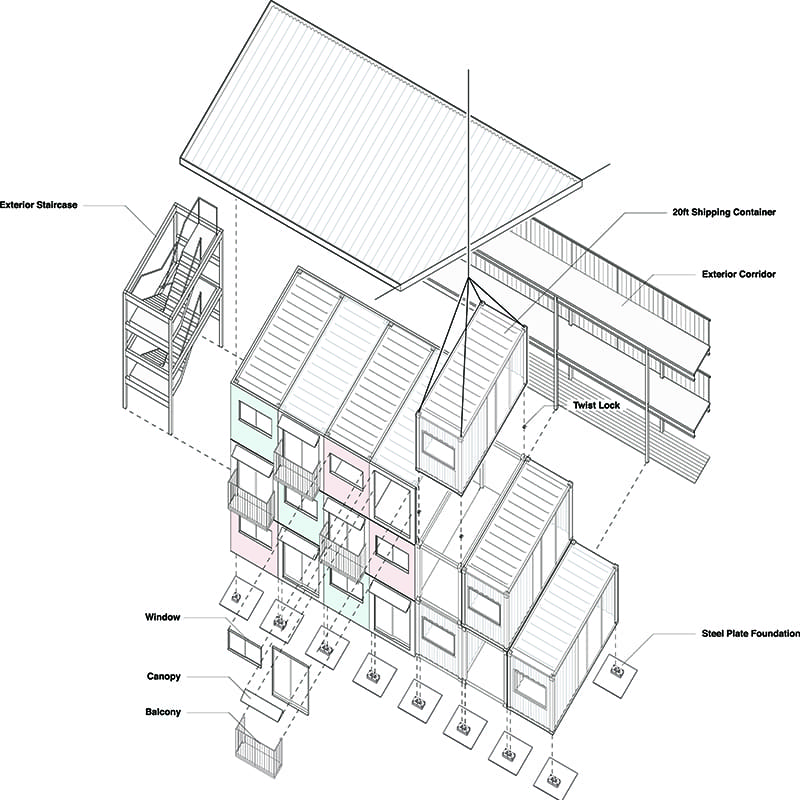

Multilevel temporary housing made from stacked shipping containers was built in Onagawa, Miyagi Prefecture, in 2011.

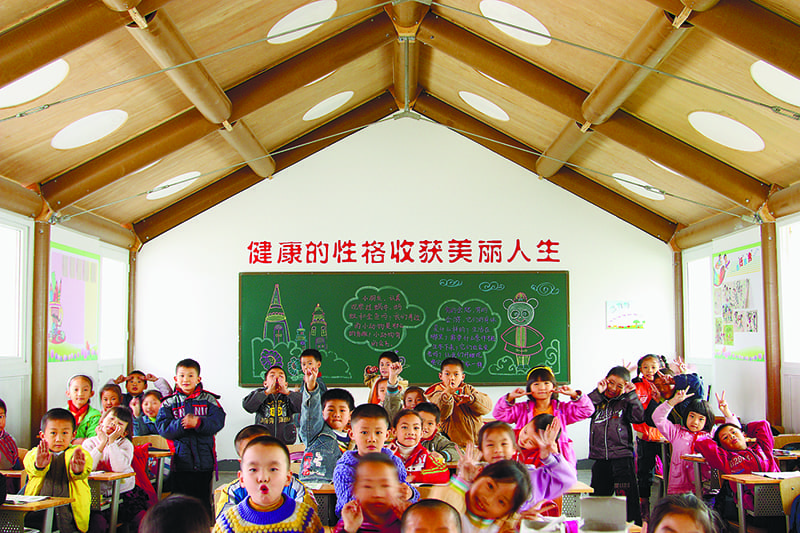

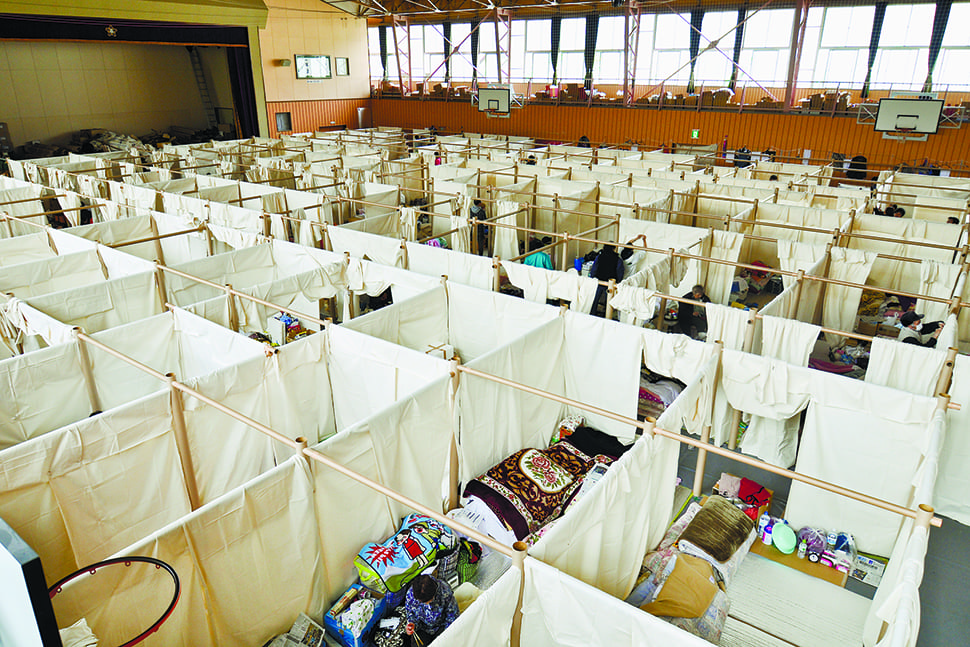

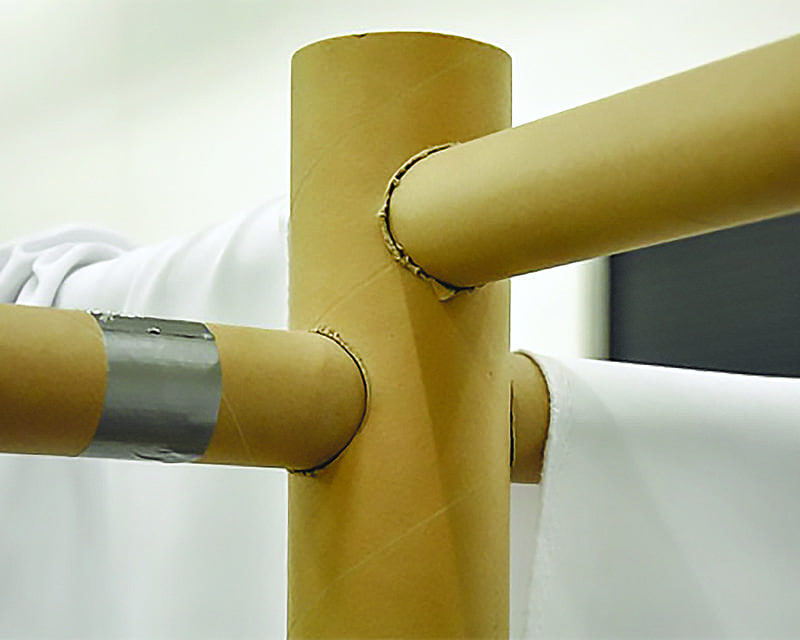

Ban’s Paper Partition System (PPS) is designed to protect the privacy of displaced people in evacuation centers. Its development began at the time of the 2004 Niigata Chuetsu Earthquake. Ban took a model of his concept to evacuation sites and repeatedly improved upon it by asking for users’ opinions. The original version of PPS was a house-shaped or enclosure-style structure made from paper honeycomb boards. In 2006, it was redesigned to become PPS3, which was composed of paper tube frames and fabric. The current system, PPS4, is an improved version of PPS3. According to Ban, the biggest hurdle in the development and diffusion of PPS was obtaining permission to install it. There were times when he attempted to give a demonstration but was not even allowed into the building housing the evacuation center.

“Government officials adhere to precedent,” Ban said, “so they don’t want to do something that hasn’t been done before. One evacuation center director even said it was easier to manage the center without partitions.” After the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, Ban’s team loaded partition materials into vans and drove in a caravan to evacuation centers in various locations. At the central sports center in the city of Yamagata, the management showed reluctance. But it seems that Democratic Party Secretary-General Katsuya Okada was there on an observation visit and liked the PPS system, and it was decided on the spot that partitions would be installed for every household group staying in the facility. After three such caravans, about 1,800 PPS units had been installed in 50 evacuation sites. PPS was subsequently used after a number of other natural disasters, including the Kumamoto Earthquake of 2016, the western Japan floods and the Hokkaido Eastern Iburi Earthquake of 2018, and the southern Kyushu floods of 2020. As of now, the governments of 58 localities, including 11 prefectures, have signed agreements with VAN for the provision of PPS in times of disaster.

Ban also designed temporary housing for Onagawa, Miyagi Prefecture, after the Great East Japan Earthquake. When the town’s mayor told him, “We need temporary housing for 190 households but there isn’t enough land for that many one-story units,” Ban proposed three-story temporary housing made from shipping containers. While conforming to the prefectural government’s general criteria on floor space and cost for temporary housing, the homes were comfortable to live in, and apparently some occupants even said they would be willing to pay rent in order to continue living there.

“An architect’s role,” Ban said, “is to solve problems and create comfortable and beautiful places to live. It’s no different for temporary housing.” He says he is also thinking about further improvements in temporary housing, in order to be prepared for the next large-scale disaster. There is no doubt that Ban’s architectural designs, born of his serious approach to the realities of disaster situations, will gain many people’s support going forward.

被災地を訪れて改良を繰り返した紙の間仕切り。

1995年1月17日に起きた阪神・淡路大震災。坂 茂の日本国内の被災者支援はここから始まった。「建築によって多くの人命が失われたことに建築家として責任を感じた」という坂は、1月末に被災地を訪れた。聖堂を焼失した教会との話し合いの結果、坂は仮設のコミュニティホール〈紙の教会〉の設計と建設を行い、仮設住宅「紙のログハウス」のプロジェクトも手掛けた。翌96年には被災者・難民支援のためのNGO、ボランタリー・アーキテクツ・ネットワーク(VAN)を設立した。

紙の間仕切りシステム(PPS)の開発が始まったのは、2004年の中越地震から。試作品を現地に持ち込み、改良を重ねた。当初はデモンストレーションをやろうとしても、避難所に入ることすらできないこともあったという。「役人は前例主義なので、前例のないことはやりたがりません」と坂は語る。2011年の東日本大震災のときは、材料をワゴン車に積んで各地を回り、50ヶ所の避難所にPPSを設置した。現在では58の自治体が災害時におけるPPSの提供に関する協定をVANと締結している。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 15 article list page