September 29, 2023

How ‘the way of tea’ conveys Japanese culture

TEA CEREMONY

Mention traditional Japanese culture and most people will think of the tea ceremony, known broadly as “sadō” or the way of tea. But what exactly is it? Simply put, the way of tea is a system of etiquette for the serving of tea by a host to a guest. Its primary expression is in the tea ceremony. It can be useful to think of a tea ceremony as a story, with each ceremony having its own theme, as chosen by its host. All of the utensils used for a ceremony will be selected in line with its theme. Hence, in truth, they are not just “utensils”; they are the “performers” that tell the story. And many of them have been used for centuries, having been lovingly passed down from generation to generation. In this way, the way of tea plays a role in preserving both objects and traditions for future generations.

On the 28th of each month, a tea ceremony honoring Sen no Rikyu, who perfected of the tea ceremony style known as “wabicha,” is held at a subtemple within the grounds of the Zen Buddhist Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto, which has long played a prominent role in the way of tea. At July’s ceremony, the host was Keiko Kitazawa, a tea ceremony instructor of the Omotesenke school (one of three schools deriving from Sen no Rikyu), and the subtemple was Zuiho-in, the family temple of Sorin Otomo, a well-known Christian feudal lord of the Sengoku Period. The theme was “fusion of the worlds of jewelry and tea.” Kitazawa, who usually lives in the suburbs of New York, paired her own tea utensils with Tiffany products borrowed from Miyoko Demay, a student of hers who used to be the president of Tiffany Japan.

According to the way of tea, the season and situation dictate the necessary rituals and utensils, and how they should be placed and handled. This fact has probably contributed to the commonly held belief that the way of tea involves many rules. In fact, the charm of the tea ceremony is that as long as hosts observe just a few key points, the rest can be carried out with relative freedom. Just as Sen no Rikyu himself famously used a fishermen’s basket as a flower vase, there is no problem with co-opting unlikely objects for use in a tea ceremony. Known as “mitate,” this can help the host give expression to their own ideas.

“Tea ceremony is a form of art that aims to create a world, and mitate is a means by which hosts can treat their guests to small surprises,” explained Kitazawa. So how did mitate feed into her choice of utensils?

Kakemono scrolls, which have long been considered the most important element of a tea ceremony, generally have words or phrases written in calligraphy that set out the ceremony’s theme. Often these will be Zen sayings, hand-written by high priests at Daitokuji or tea ceremony masters, or waka poems expressing the seasons. However, for the July ceremony Kitazawa chose one with the English phrase “Simplicity & Balance.” It was written by Dr. Shukuro Manabe, who won the Nobel Prize in physics in 2021. Kitazawa’s choice is indicative of her passion to share Japanese culture with the world in a way that is easy to understand. The true pleasure of the tea ceremony is to try to ascertain from the kakemono and other utensils what the host’s intentions for the ceremony are, and then to fully appreciate the thought that went into them. In this way, through the course of enjoying a bowl of tea, the host’s and guest’s hearts become one in a process known as “ichiza konryū.” In other words, a tea ceremony is never a one-sided event where the host entertains their guests; it actually relies on the guests being aware of their own role, and seeking to understand and respond to the host’s intentions.

Below the kakemono is an arrangement of flowers. In July, a vintage Tiffany hand-blown Venetian glass vase was used. Furthermore, on the tatami mat where the tea was prepared, there was a traditional stove and pot, and next to it a Louis Vuitton travel trunk, which played the role of a chest that might be used when making tea during a trip. Inside was an antique Baccarat ice bucket that was being used as a mizusashi water container. The main tea bowl was a Joseon Dynasty Korai tea bowl, a type that has been loved by tea masters since ancient times, and this one in particular was of the hansu (interpreter) type.

PHOTOS: KOUTARO WASHIZAKI

Incidentally, in the tea ceremony there is a long history of inscribing important utensils, and when such items are used they generally convey a particularly significant message. Inscriptions on the chashaku tea scoops are considered equivalent in significance to the kakemono itself. The chashaku used by Kitazawa on this day was inscribed with “tabigoromo” (“travel clothes”). The guests were thus able to realize the secret theme of this tea ceremony: travel (tabi). In keeping with the theme, other items that had been passed down over generations from Europe and America, as well as utensils with inscriptions associated with foreign exchange, were also used. These choices no doubt reflected Kitazawa’s personal journeys between Japan and New York, and also the journeys the tools had taken over the centuries.

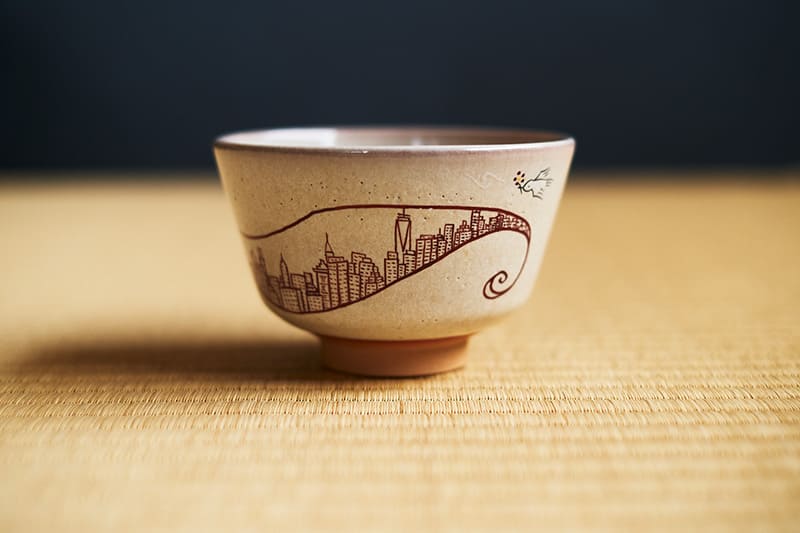

Also featured in the ceremony were tea bowls that Kitazawa had ordered especially from contemporary artists.

“I like to use utensils made by contemporary artists, in addition to heirlooms. If I didn’t do that, with the number of people doing tea ceremony in decline, the number of people who can actually make the utensils would decline as well. And if that happened then the quality of traditional Japanese crafts in general, from ceramics to woodworking and lacquerware, would also decline.”

And of course, utensils do on occasion break. Many of the tea bowls that have been designated as important cultural properties in Japan, or that are now held in museums, bear the hallmarks of past repairs, and so it is due to the efforts of talented craftspeople that they even exist today. In this way, nurturing skilled craftspeople is essential to ensure not only that new utensils can be made in the future, but that the old ones can be preserved. Looking at the assortment of utensils gathered for Kitazawa’s ceremony, we can see that while the eras and places of production are quite different, each is brimming with the spirit and skill of a craftsman. The owner of a long-established three-star restaurant in France observed, “Three-star restaurants exist to protect and nurture the traditional crafts of a region, from the architecture to the interior decoration to tableware.” Likewise, the way of tea is not just a ceremony. It plays a crucial role in preserving, nurturing and passing on both the physical artifacts and the spirit of traditional Japanese culture.

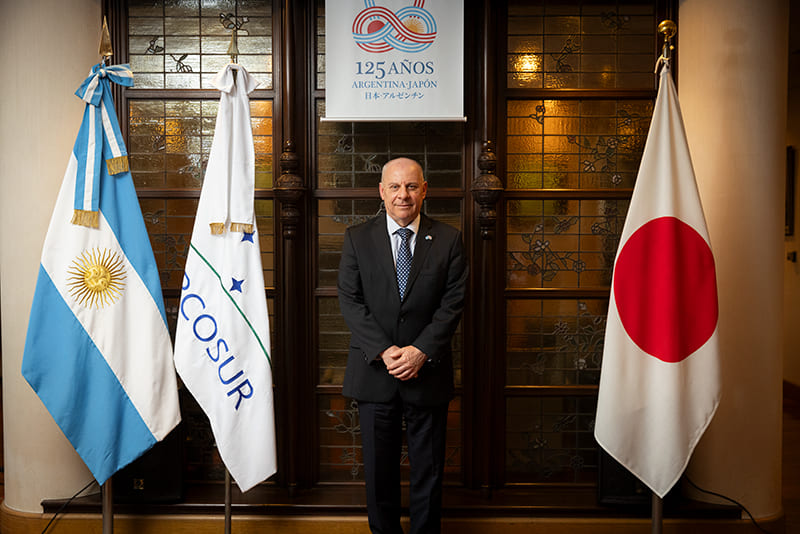

KEIKO KITAZAWA

Born in Nara Prefecture. After working as an interior designer, she moved to the United States in her 20s to become an artist. Fascinated by the artistic possibilities afforded by the way of tea (chanoyu), she became an instructor of the Omotesenke school. She holds tea ceremony classes and public tea ceremonies throughout New Jersey and New York. She was an inaugural member of the Omotesenke Domonkai Eastern Region, USA, which was established in 2010, and has served as its secretary-general since 2019. She is dedicated to introducing chanoyu to a wide audience, and believes not only that it should be part of everyday life but that one’s lifestyle will reflect one’s approach to chanoyu.

MIYOKO DEMAY

In 1992, she joined Tiffany & Co.’s business sales division in New York. After various global roles at the corporate headquarters, she was appointed President of Tiffany Japan in 2021. She retired from Tiffany at the end of last year. She has now launched Demay Luxury Consulting and is active in Japan and New York. She is studying the tea ceremony while serving as a member of the Advisory Council for Women’s Initiatives at the Japan Society in New York and as vice chair of the Women in Business Committee at the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan.

茶道はお茶の儀式にあらず。茶会から考える、日本文化の心。

今回は今年7月に京都·大徳寺の塔頭(たっちゅう)、瑞峯院にて、茶道表千家流講師、北澤恵子が亭主を務めた茶会を通じて、日本の伝統文化においてモノ·コトがどのように過去から未来へと引き継がれているのかを紹介する。

茶会のテーマは「世界の宝飾品と茶道具の融合」。米国在住の北澤の道具とともに、〈ティファニー〉製品などを茶道具に見立てて取り合わせる。元々、別の用途で使われていた道具を茶道具とみなして扱う「見立て」は、特にアイデアが生きる表現方法だ。また、道具から亭主の意図を読み取り、その心配りに思いを寄せることが茶会の醍醐味でもある。

英語で書かれた掛物や〈ルイ ヴィトン〉〈バカラ〉などの製品と共に、北澤が自ら現代作家に特注した茶碗も登場した。道具は破損することもあり、次世代に手渡すためにはそれを作り、修理する技術をもった職人も支えなくてはならない。茶道は単なるお茶の儀式にあらず。日本における物質、精神の双方にまつわる文化を守り、育て、伝えるという役割を果たしているのだ。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 28 article list page