April 25, 2025

Lacquer artist applies craft spirit to Noto’s revival

TRADITIONAL CRAFTS

At 4:10 p.m. on Jan. 1, 2024, the Noto region of Ishikawa Prefecture was hit by an earthquake that had a maximum intensity of 7 on the Japanese scale. The quake and the tsunamis it spawned destroyed houses where people had been celebrating New Year’s Day. The neighboring prefectures of Niigata, Toyama, Fukui and Gifu suffered damage as well. As of March 11 this year, 549 people had died — including 321 as a direct result of the disaster — two remained missing and 1,393 had been injured, according to the Cabinet Office.

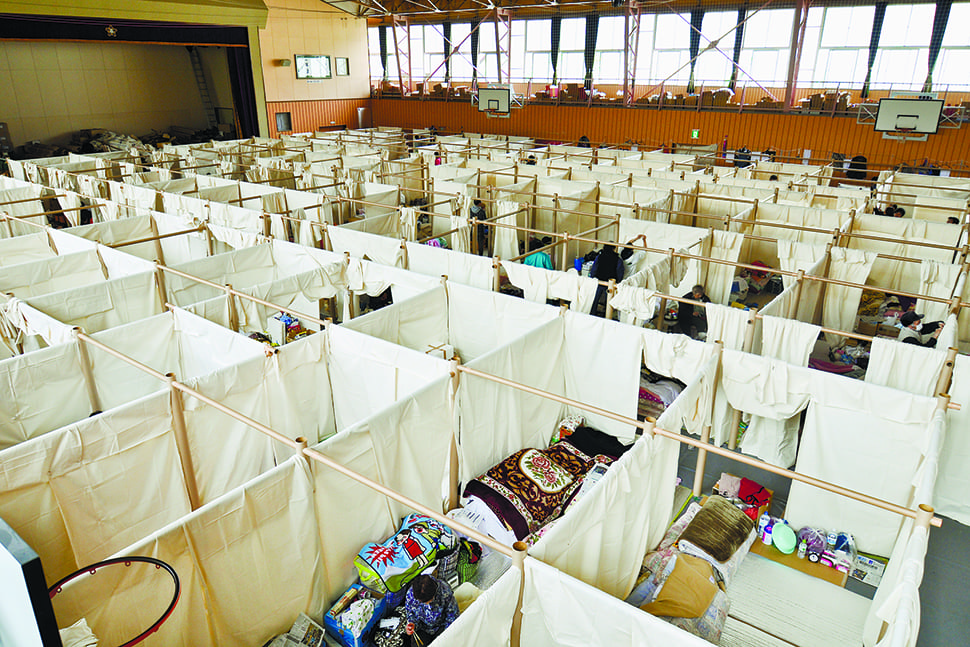

Damage to property included 6,483 totally destroyed houses, 23,458 partially destroyed houses and more than 160,000 partially damaged houses. As of Feb. 4, 34,000 people had been evacuated, with last September’s torrential rains compounding the area’s difficulties. More than 20,000 people are still living in the 6,882 temporary housing units set up by the prefectural government in 10 cities and towns or in “deemed temporary housing” rented for them by the government.

The evacuees include many artists and craftspeople who sustain Ishikawa’s reputation as a craft center. The 103 companies that make up the Wajima Lacquerware Manufacturers Cooperative saw 17 offices burn down in the fires that hit Wajima’s Asaichi market area during the quake and 50 suffer partial or complete damage. If their plight is left unaddressed, the traditional crafts of Noto and the prefecture as a whole will inevitably decline.

One of those who is standing up to address the situation — and save the technique known as Wajima-nuri — is lacquerware artist Akito Akagi.

Wajima-nuri lacquerware is made possible by a network of 124 specialized craftspeople, from woodworkers to polishers and lacquer artists. The loss of just one of those roles would mean that Wajima-nuri lacquerware could no longer be made. The industry was already suffering from a dearth of young craftspeople to succeed the older generation and the earthquake made the problem a lot worse.

Akagi, whose own workshop survived the quake unscathed, started by using social media to call for help and donations for his so-called Small Woodworker Restoration Project. With these proceeds, he was able to rebuild the residence and workshop of Mitsuo Ikeshita (then 86 years old), a woodworker who specialized in making bowls — and whose predecessors had worked in Wajima for generations since the Edo Period (1603-1868). The successful restoration of the workshop at the end of March 2024 received nationwide coverage in the news, and lit a flicker of hope for the crafts of Noto.

“Some people said it was pointless to rebuild Ikeshita’s workshop because he was too old and had no apprentices to succeed him,” Akagi said. “But two young craftsmen from my workshop went over to become his apprentices. Ikeshita returned home from what was his second temporary residence, and happily got back to work. He did some work with the apprentices, but on July 1, three months after the workshop reopened, he passed away.”

Toshihiro Yamane, a 76-year-old woodworker who took over Ikeshita’s workshop, later passed away in November. Now Yamane’s son Toshiyuki, who was working as a temporary worker in an automobile factory after the earthquake, is continuing his father’s work while living in temporary housing.

“It will take at least five years for the two apprentice woodworkers to become full-fledged craftspeople,” Akagi said. “Since they cannot shape difficult bowls yet, they are working on flat objects like plates. Before the earthquake, 80% of the bowls made in Wajima were my work, and I had five woodworkers to supply me with bowls, but since the earthquake they have all passed away or closed shop, so there is no one left I can ask. We are 90% short of people, workshops and tools. Right now, we are lacquering wood from a large stockpile, and we’re holding out hope that the Wajima-nuri system can be restored before that stock runs out.”

The government is also acting to restore Wajima-nuri. Late last January, one year after the earthquake, a temporary Wajima-nuri facility fully subsidized by the government became available to craftspeople from 82 workshops.

“Young people and young craftspeople need to settle in Noto in order to carry on the Wajima-nuri tradition and revive Noto,” said Akagi, whose other efforts include preserving the townscape and operating a restaurant.

“Because of the principle that public funds cannot be put into privately owned property, there are basically no subsidies for repairing damaged houses, although there are subsidies for demolishing and clearing away damaged dwellings. But if the houses can’t be repaired, people move away and don’t come back,” he said.

In addition to the restoration of houses, he is also involved in preserving the streetscapes of black tile-roofed Japanese houses that give the area its unique scenery.

“After the Great East Japan Earthquake, I visited Tohoku many times and often heard people say they felt a great sense of loss at the disappearance of their old street-scapes. I wanted to do something to prevent that from occurring here, so I submitted a petition to the Cabinet Office to restore the old houses of Noto and preserve the historical townscape and landscape,” he said.

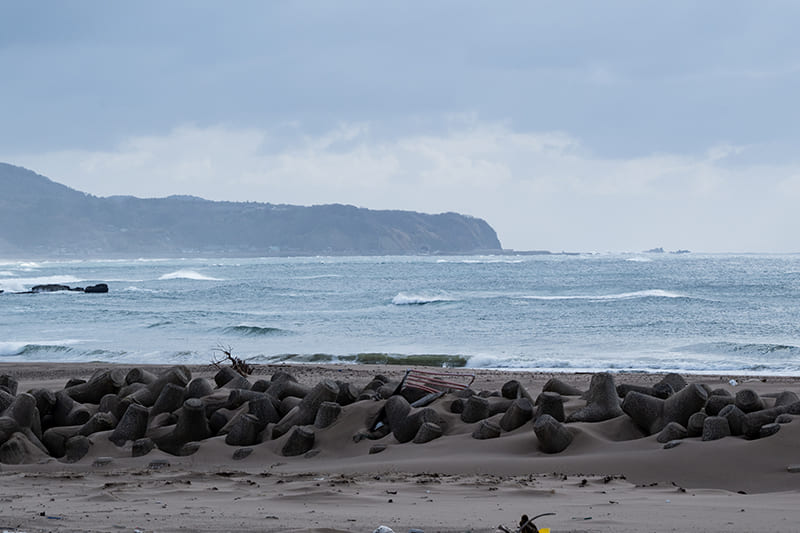

Saryo Somamichi, a small inn offering Japanese cuisine that Akagi opened in 2023, was also damaged by the earthquake. While the building is undergoing repairs, he opened the temporary Somamichi Seaside Restaurant. His broader plans for restoration also include using the temple hall to build a music hall and opening a liquor store, bar and bookstore.

“If we do all that, young people may eventually move in and start their own fashionable cafes. I myself am an ‘outsider,’ having moved to Noto after I was born in Okayama and lived in Tokyo. So I understand the beauty of this land. This year will be my 36th year since moving here, and I want to repay my debt to Noto for accepting me,” he said.

Involving both the historical landscape and traditional crafts that came to define the region, Akagi’s plans might hold the key to a true restoration of Noto.

AKITO AKAGI

Born in Okayama in 1962. Graduated with a degree in philosophy from Chuo University. After working as an editor, Akagi moved to Wajima in 1988. He trained under the Wajima-nuri lacquerware craftsman Susumu Okamoto and opened his own studio in 1994. He pioneered the use of lacquerware for daily use in modern life. In 2023, he opened Saryo Somamichi, an inn offering Japanese cuisine. He founded the publishing company Stillmind and is a prolific writer, with his works including “Utsukushii Koto” (“Beautiful Things”), which has been used in a Japanese-language textbook for high school students.

工藝的な視点から、能登の復興に携わる塗師。

「令和6年能登半島地震」により、能登、ひいては石川県全体の伝統工芸が衰退の危機にある。そんな状況下、塗師・赤木明登は輪島塗の再建に向けていち早く立ち上がった。寄付を集って、木地師の工房を再建すると共に、自分の弟子を木地師に育て上げるべく、工房に送り込んだ。だが、職人として一人前になるには時間がかかる。伝統工芸を復活させるには「人、場所、道具の9割が足りていません」とも赤木は語る。

家屋修復と同時に進めているのが、能登の美しい景観を支える黒瓦を特徴とする日本家屋の街並みの保存だ。そのために内閣府に陳情も提出した。さらに寺院を利用して音楽堂を作る計画があるほか、酒屋やバー、本屋も作りたいと赤木は能登復興の構想を語る。

「僕は岡山で生まれた “よそ者”だからこそ、この土地のよさ、美しさがわかるんです。今年、移住して36年目。よそ者である僕を受け入れてくれた恩返しをしたい」。能登を支えてきた工芸と歴史的景観を継承する。赤木が提唱する復興こそ、真に望まれることではないだろうか。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 47 article list page