March 08, 2021

Sho Okiyama, doctor teaching AI expert skills for future

Ten years ago, Dr. Sho Okiyama was living an interesting life. As one of two doctors in a small hospital on the Okinawa island of Ishigaki, his nights were either a flying adventure or a rather boring study session.

The good shifts offered patients, with a hurried helicopter ride to one of the island’s remote communities. The slower nights saw the fresh-faced 28-year-old in his small office, studying medical videos online.

It was so unlike his time working in an ER in Tokyo, where every shift meant a new challenge and a new chance to learn from his more experienced senior doctors. Ishigaki might be slower, but when the challenges came he faced them alone.

The young doctor’s face clouds a little when he talks about those nights. “On the slower nights, I had to study. I would think, ‘If only I had that surgical skill’ or ‘How can I have the eyes of (a more experienced) doctor, or the ears of another?’ I wanted to be both a generalist and a specialist, but this is impossible. It takes time to become an expert in all the areas, and I just didn’t think I could do it within my lifetime.” Acting alone, as the sole physician on an island, made him acutely aware that all doctors are in some ways practicing alone, with the responsibility for their patients’ lives in their hands.

From helicopter to startup

Ten years later, Dr. Okiyama is practicing a different kind of medicine. Instead of flying in helicopters, he is the founder of Aillis, a Japanese medical device startup that builds AI-powered tools for doctors all around the world.

Its first product is hardware: a small, purpose-built oral camera that takes a rapid series of photographs of a patient’s throat and pharynx.

Its second product is the camera’s software, which analyzes the photos to provide a highly accurate influenza diagnosis.

“There are minute differences between the different kinds of inflammations within the throat,” he said. “In fact, the most challenging part of diagnosis is eliminating the other kinds of infection, which present very subtle differences in inflammation patterns on the throat, tonsils and larynx. It is here that most doctors have the most difficulty, and this results in a very high amount of misdiagnosis. Machine learning can be more successful in making that distinction.”

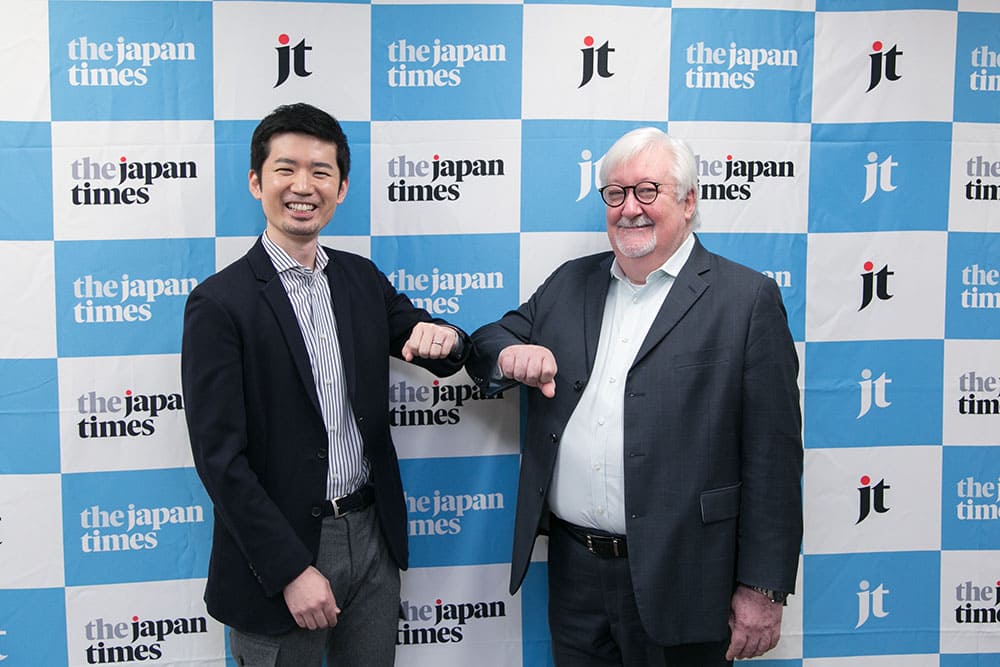

Watching him during his appearance at The Japan Times’ sustainability roundtable series, the fresh-faced, goateed doctor seemed too young to be changing medicine itself. Learning more about this soft-spoken man’s life explains his unique character. Raised abroad, first in Philadelphia and then as a teenager in Rome, he returned to Japan to attend school here. In his gentle, fluent English, Okiyama described his overwhelming desire to “see the people I was helping immediately, in front of me, to see their smiles. So it seemed that the two choices for a career were either teacher or doctor.” He chose medical college, which allowed him to graduate faster than his American counterparts, who must first go through undergraduate school.

A new theory of knowledge

It was during medical school and in his practice afterward that he developed a unique taxonomy of medical knowledge. “I decided there are two types of knowledge: ‘stock’ knowledge and ‘cycle’ knowledge. Stock knowledge is… information which can be accumulated and stored, put into libraries. But there are certain types of knowledge that cannot be described verbally, which I call cycle knowledge. Examples of this might be medical technique, or medical skills like examination. These skills are learned through practice and experience, and this takes time. I can add to the stock knowledge by publishing a paper. But even If I live to 100 years old and become an expert, skillful doctor, when I’m gone I cannot leave my skills behind.”

When asked which kind of knowledge is more important for practicing medicine as a doctor, Okiyama didn’t hesitate. He has come to believe that a doctor’s skill is 20 percent stock knowledge and 80 percent cycle knowledge. Considering how slowly cycle knowledge accumulates, and the fleeting nature of acquired skills, improvement of the medical field can be seen as a unique engineering problem. If this cycle knowledge could be gathered and stored beyond the time period of a single doctor’s life, then all of medicine would improve. But how?

The new tool: AI

The answer seemed clear: artificial intelligence. Okiyama compares the development of AI to humans’ development of writing: before writing, all knowledge was cycle knowledge. Just as the written word allowed for basic information to be recorded, AI will do the same with the more complex information of technique. Instead of describing techniques, an AI will perform them. “There are chess-playing AI these days that can beat champions. Even if I read a book by a grand master, I cannot become a chess expert the next day. But if I preserve that grand master’s knowledge and skills in an AI, then the expert’s skills become instantly useful to me. With a smartphone, I might be able to beat another grand master using that AI.” Okiyama sees AI as the ultimate tool for medicine, where the stakes are much higher than in chess. For a doctor, the disease is the opponent.

Taking risks to help medicine

Such grand ambitions seem to come naturally to Okiyama, but he worries that other Japanese doctors feel pressure to not take risks. For instance, fewer doctors create medical startups in Japan compared to the USA, a fact that he mourns. In Japan, the prestige of a doctor’s position in their hospital or practice is considerable. It can create a kind of pressure to never give that position up, even if they have ideas for startups or new medical technology. “To younger doctors, I would tell them that taking risks is essential to changing medicine. The risks may not be as big as you think they are. Even if you fail, you’re a doctor — you will always have a way of earning a living. This is a reason to take risks. Give it a go! That’s my message.”

With Aillis’s first two products currently awaiting approval, Okiyama sees huge potential for what might come next, both for Aillis and for the use of AI in medicine. “We have plans and beta software for other diseases. The throat and pharynx contain so much rich information. Remember, this is the inside of the body. We can see the blood vessels running behind the walls, the inflammatory patterns. The tonsils can tell us if an infection is bacterial or viral…” He stops himself, a little shy at his own enthusiasm. Okiyama might have big plans, but he is still too modest to talk big.

More than his ambitions for his own startup, it is Okiyama’s vision for all of medicine that leaves the biggest impression. On Ishigaki, many of his patients still consulted shamans, an ancient tradition that many island families practice. When faced with a difficult medical decision over treatment or surgery, shamans provided principled and trusted advice, acting almost like a partner to the doctor. “Maybe in the future, a patient’s diagnosis and options may come from the AI system. And we doctors would be more on the patient’s side, consulting them.”

At the memory of the islands, Okiyama smiled. “Almost like a shaman.”