January 09, 2022

Kicking for inclusion: How soccer is helping homeless

When you see an adult soccer team practicing in Japan, you usually don’t pay much attention. They will be running or resting in their scrimmage jerseys, faces flushed. If it is an outside field on a winter day, you might see steam rising through the air as they rest. If it is an indoor futsal field, you might hear their yells or laughter echoing through the hall. If you bother to give them a second glance, it will be a kind one: Here is a group of healthy adults, doing something we should all do more of: playing.

But what if there was something special about that team? What if some of the players desperately needed this friendly game? If it was their only opportunity this week to talk to others? What if this casual practice, seemingly so common, was their only chance to score, or win, or contribute? They might be wearing scrimmage jerseys and athletic clothes. But afterward, that might change. What if many of those soccer players you barely noticed were actually homeless?

Soccer as social fabric

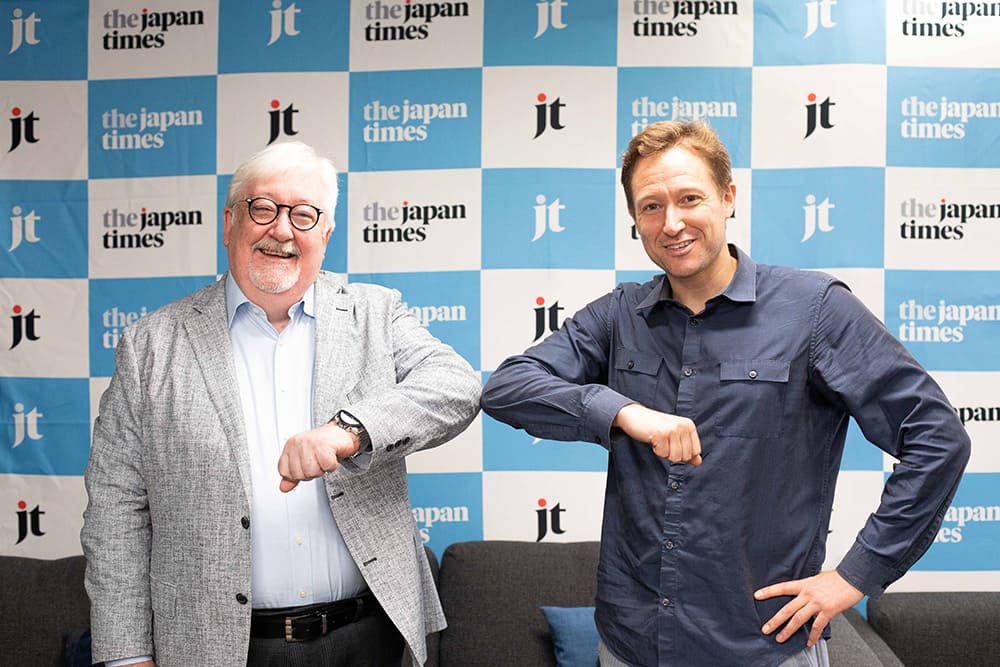

Roundtable by The Japan Times, hosted by Ross Rowbury, started the new year with a fascinating new interview. Naofumi Suzuki is the executive director of the Diversity Soccer Association (DSA). An academic with a Ph.D., Suzuki studies the use of sports in healing and inclusion. He sees sports as a crucial way to find and help Japan’s homeless, who are often people with mental illness, depression or unfortunate family circumstances. One of the ways he is doing that is by leading the Diversity Soccer Association, which organizes soccer games and tournaments for homeless people in Tokyo and Osaka. They call their players “nobushi soccer” players, from a word meaning “wandering samurai.”

“We want to make the footballing environment as inclusive as possible. We don’t set the bar too high,” Suzuki said. “We customize the rules according to the situation the participants are in. For example, if they are lacking self-confidence, we start with small exercises, like introducing themselves. We make it a fun exercise to get everyone to relax. And we make the football part enjoyable for anyone. This gives a foundation for the participants to build their confidence. We also try to invite those who are not excluded — people who might be called ‘normal’ — so that they can meet our players.”At this point, Suzuki smiled modestly.

“I was one of them. I had never met homeless people closely before. But this activity was so easy. It gave me an idea of who they are. And you know what? They’re just people. We don’t have a lot of opportunities to do that in our daily lives. And that … that’s the real exclusion.”

Special care for everyone

The DSA isn’t all play. Suzuki explained that those who have lost confidence in themselves can often need extra help: “Some of our participants have situations where care is needed. For instance, they might have a difficult family environment. So we use a kind of gatekeeper to engage with participants. These gatekeepers are trained professionals from different areas. We have social workers, psychiatrists and a very experienced counselor who helps our participants feel comfortable and who ensures the experience is a good one for them.”

When asked by Rowbury about his background, the slender, athletic Suzuki revealed that sports has always been a big part of his life. “I have always loved sports. I played baseball, basketball, and I still coach lacrosse. Going through these experiences gave me everything, really. So when I went to college and had to do academic stuff, I had to make that connection. I had to connect my passion with academics. Really, I wanted to make this sport, this thing that I love, be good for society. There is sometimes violence and bad stuff in sports. So my research focused on how we could make sports a good thing.”

Inclusion for all

Rowbury was especially curious about the aspect of inclusion in Suzuki’s work with the homeless. The enthusiastic host explained: “I like to say that we’ve experienced the first wave of D&I [diversity and inclusion] in Japan. That was gender. Now it’s LBGT. In Japan, you wonder: What’s next? Last week, when you and I talked about inclusion, it was different. It was homelessness, it was mental stress, it was a whole range of things we need to think holistically about, not just gender or other issues that are more visible. Because of that reason, I feel the work you’re doing is incredibly important.”

Suzuki’s thoughts on inclusion were framed by his experience with sports. “You may be better during a game. But if you change the rules, you may be rubbish. It may not be solely your ability that is deciding your success. If the environment changes, your ability changes.” He elaborated on this point, driving it home eloquently: “The social institution matters to your ability. Making an inclusive society is hard. It sounds great, but it’s tough. The existing institution is made for those who are already included. The new group might not fit. So we may need to make changes to the institution. That involves giving up some of your share, the stuff you’ve been enjoying, and allowing in the new members. But you can enjoy that process, too.”

What comes next for this group of social workers, academics and sports enthusiasts who use the sport of soccer to help Japan’s excluded? With COVID halting their annual tournament, Suzuki’s group has had to change tactics, holding only smaller games and even distributing tablets to players so they can keep in touch with the organization and each other. “I was really frustrated during this period. I felt lost. Where are the people who are struggling? What are they struggling with? I think it’s time to rebuild the social fabric so we can help each other. We need to bring the fabric back.”

As the pandemic’s restrictions end, Suzuki is excited to bring back nobushi soccer on a bigger scale. “You see, Nobushi Japan started as a program to send a national team to the Homeless World Cup. It’s a worldwide competition, and we haven’t done this since 2011. To do that, we need a bigger pool of players to select a team from. I hope that an expansion to a league format will accomplish this.”

The next time you walk by a group of adults playing soccer, remember that this practice might be more than just a game. It might be a little bit of that precious social fabric Suzuki was talking about, where everyone can be included.