November 29, 2021

Upopoy Museum is a space for mutual respect

ARCHITECTURE

PHOTOS:KOUTARO WASHIZAKI

After a 40-minute drive from New Chitose Airport across Hokkaido’s wide expanses, the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park comes into view on the richly forested shores of a lake in the town of Shiraoi. Dedicated to sharing the culture of the indigenous people of northern Japan, the facility opened in 2020 as a symbol of a society based on mutual respect and coexistence.

Multiple spaces around the translucent blue waters of Lake Poroto offer visitors many ways to experience Ainu culture. As well as the central National Ainu Museum, there is the Crafts Studio, dedicated to traditional Ainu crafts; the Cultural Exchange Hall, where performances incorporating Ainu dance and musical instruments are held; and a re-created Ainu kotan (village) offering firsthand insight into traditional lifestyles. There is so much to see and do that visitors can spend an entire day at Upopoy without exhausting the possibilities.

2-3 Wakakusa-cho, Shiraoi Town, Shiraoi District, Hokkaido 059-0902

Opening hours: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. (through March 31, 2022). Closed on Mondays, or the next business day when Monday is a holiday. Closed from Dec. 29 to Jan. 3 for New Year’s. Entrance fee: ¥1,200

Website: https://ainu-upopoy.jp/en/

PHOTOS: KOUTAROU WASHIZAKI

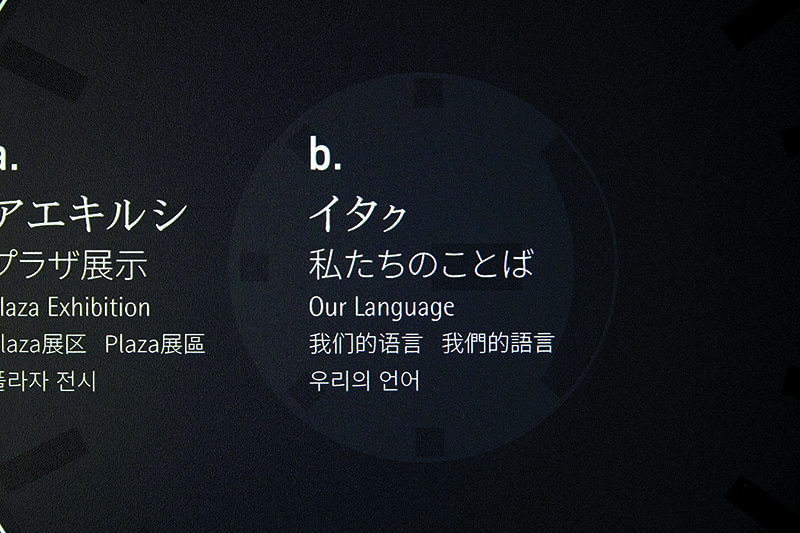

Upopoy was conceived amid hopes for a flourishing renewal for the Ainu culture, long imperiled by the ethnic discrimination and assimilation policies introduced in the Meiji Era. Symbolizing these hopes, Ainu is the main language of the facility’s signage, and permanent exhibits are named with the Ainu people as subject: Urespa (Our Lives), Itak (Our Language). According to Manager of Exhibition Planning Division Masato Tamura, the exhibits and their signs build on a vast body of research by linguists specializing in the language, plus by people learning and teaching it in various regions. “The Ainu language has many dialects, and nothing you could call a common standard,” Tamura said. “For that reason, we enlisted the help of numerous scholars and strove to respect the dialect of each region in Upopoy’s signage. A total of eight other languages are used on the signs as well, which is a message that, in addition to the Ainu, a wide range of peoples live in Japan.”

One place at Upopoy that should not be overlooked is the Memorial Site, which stores ancestral Ainu remains and burial goods that were disinterred from their original burial sites and carried away. The site, about a kilometer away from the main part of Upopoy, stands on a small hill overlooking the sea. Why should a national cultural facility need a memorial site nearby? The answer to this question lies in the history of the disinterment of Ainu remains.

In the latter half of the 19th century, when Japanese officials learned that staffers at the British Consulate in Hokkaido had exhumed the remains of 16 Ainu people from a kotan’s graveyard without permission, the matter became a major international incident. Physical anthropology was highly esteemed in Britain at the time, and the bones were viewed as valuable materials for research into the traits of the Ainu people. The exhumations were treated as a serious crime, and the staffers involved were punished severely.

In the early 20th century, however, Japanese universities began exhuming the remains of Ainu people themselves, accumulating large collections in the name of research. Hokkaido University became the center of this movement, and by the mid-20th century the remains of over a thousand Ainu people had been exhumed from their burial sites. The Ainu steadfastly opposed this desecration of their ancestors’ graves, but their protests and demands were all but ignored. Between 1985 and 2001, just 35 sets of ancestral remains were returned. Even after this period, Hokkaido University, which was responsible for storing the remains, refused requests to return them, on the grounds that it would hinder research.

The cemetery where remains and burial goods are stored.

Beside it stand a memorial service facility and a monument shaped like an ikupasuy (a kind of ritual implement), symbolizing the site’s mission.

PHOTOS:KOUTARO WASHIZAKI

PHOTOS:KOUTARO WASHIZAKI

However, following the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, and rising interest in the plights of indigenous peoples around the world, progress was made on the return of remains, and those that could not be returned immediately were gathered at Upopoy, with memorial services to be held by Ainu people.

Many issues related to the treatment of the remains are yet to be resolved. In Japan, it is thought normal to entrust remains to family members or descendants, but it should not be forgotten that this is a wajin (ethnic Japanese) way of thinking. When an Ainu person dies, they are mourned by their entire village, and it can be difficult to clearly identify individual descendants for remains to be returned to. This has been a sticking point for demands for the return of ancestral Ainu remains in the past, leading to prolonged debate, but in recent years the idea of returning remains to groups instead of individuals has found more acceptance. Remains that could not be immediately returned even under these conditions were gathered at the Upopoy memorial site, where ritual memorial services would be performed by Ainu people.

The Upopoy memorial site was completed in September 2019, with the first memorial service by Ainu people held in December. When visiting Upopoy, which urges us to envisage a harmonious society, now and in the future, this history has much to teach us.

民族の共生を目指す空間、国立文化施設「ウポポイ」。

2020年開業の、国立の文化施設「ウポポイ(民族共生象徴空間)」は、アイヌ文化継承を行い、異なる人々を尊重・共生していく社会の象徴となることを目指した空間だ。園内には国立アイヌ民族博物館を中心に、アイヌ文化を体験できる施設がある。

このウポポイにおいて、ひとつ忘れてはならない場所がある。過去に墓を掘り返され持ち出されたアイヌ民族の遺骨と副葬品を収める慰霊施設だ。20世紀初頭、研究活動の名目で日本の大学がアイヌ民族の遺骨の収集を行なっていた。アイヌの人々は抗議を続けたが、その要求が聞き入られることはなかった。しかし2007年の国連「先住民族の権利に関する国際連合宣言」以降、先住民族への国際的な関心が高まるなか、遺骨の返還が進められ、直ちに返還できない遺骨などについてはウポポイに集約され、アイヌによる慰霊が行われることとなった。

未来の共生社会を訴えるウポポイにおいて、私たちはこれらの歴史から学ぶことが数多くあるだろう。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 6 article list page