April 21, 2023

The Atomic Bomb Dome, a symbol of peace

MEMORIAL PARK

PHOTO: KOUTAROU WASHIZAKI

It is deeply meaningful that this year’s Group of Seven summit will be held in Hiroshima, a city that symbolizes the anti-nuclear and anti-war movements. Seventy-eight years after participating nations were enemies in World War II, their leaders will gather from May 19 through 21 in the city that suffered the first atomic bombing during the war. Probably the most well-known symbol of peace in Hiroshima is the Atomic Bomb Dome (Genbaku Dome), part of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, where a ceremony is held every Aug. 6 to mark the anniversary of the 1945 bombing. This article tells the story of how the park came to be and why the dome, a symbol of sorrow for Hiroshima’s citizens at the time, was left intact.

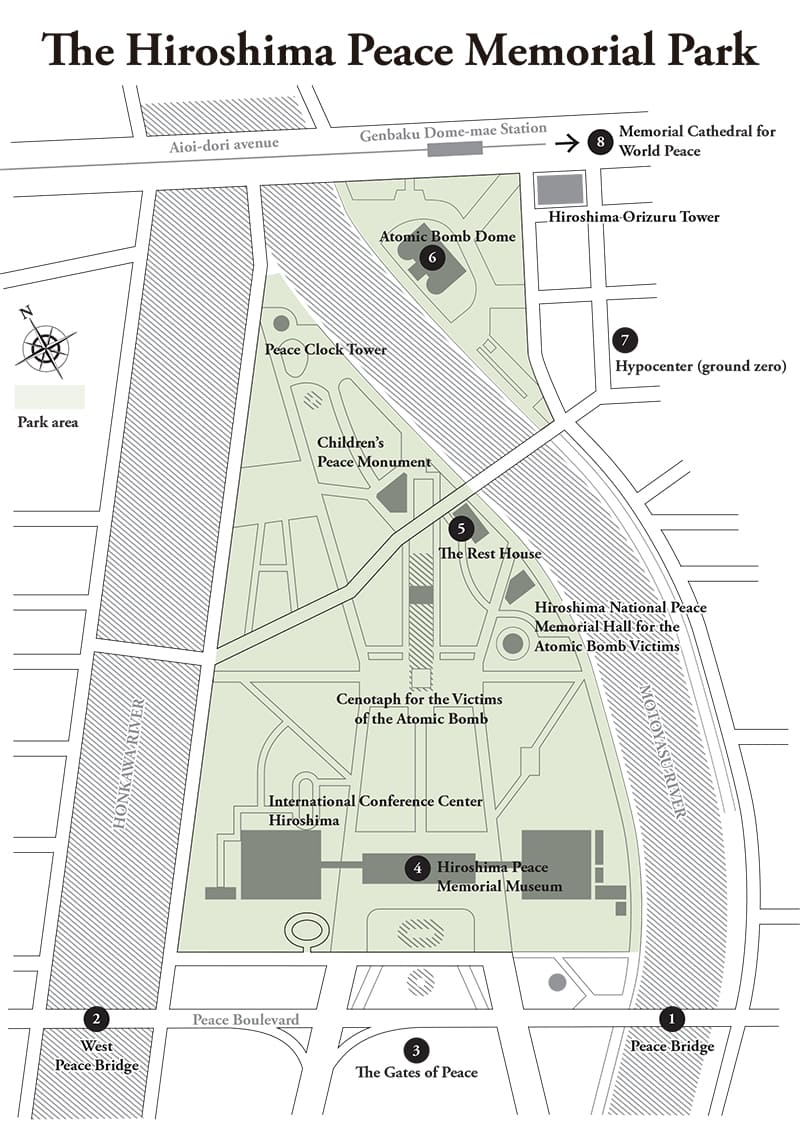

The park was designed by Kenzo Tange (1913–2005), one of Japan’s most renowned architects, and completed in 1955. When visitors enter the park from Peace Boulevard, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (whose main building also was completed in 1955) comes into view straight ahead. Passing between the museum’s pilotis, the columns on which it stands, visitors see the cenotaph for the victims of the bombing, and beyond that the dome. A single axis runs through the park, connecting the museum, the cenotaph and the dome in a straight line.

Tange spent his early years in Imabari, a city in Ehime Prefecture, and attended high school in Hiroshima, not far away across the Seto Inland Sea. He left the region to attend Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo), but in August 1945 received word that his father was critically ill and set out immediately for his hometown. When he reached the Hiroshima Prefecture city of Onomichi, he learned that an atomic bomb had been dropped on the city of Hiroshima, about 90 kilometers to the east. What awaited him in Imabari was not only his father’s death but his mother’s as well; she had been killed in the Aug. 6 bombing of Imabari. There is no question that in the eyes of the young Tange, the deaths of his parents overlapped with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Following defeat in the war, the government established the War Damage Reconstruction Board, and architects began drawing up reconstruction plans for cities nationwide. But at a time when people believed plants would not grow in Hiroshima for 70 years and a visit to the city would cause death by radiation sickness, no one volunteered to take on planning there. Tange offered to take the lead in the city’s reconstruction. In the summer of 1946, just a year after the bomb was dropped, Tange came to the city with two members of his laboratory at the University of Tokyo. According to Sachio Otani (1924–2013), one of the architects who accompanied him, reconstruction planning typically began by obtaining maps of a city and walking its neighborhoods, but in central Hiroshima the devastation and still-untouched rubble was so extensive, the three were unable to discern the traces of the former city even with maps in hand. Food was scarce, but they managed to find enough supplies on the black market to continue their work. The planning document that Tange poured such emotion into under these difficult circumstances was reflected in the plan that the Hiroshima City Council approved in 1947.

In May 1949, a design competition was announced for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. It called for both park landscaping and facilities such as a museum and public hall. The question was how to arrange the facilities within the park. In his entry, Tange proposed drawing a line straight from a road running east to west across the site’s southern end to the dome in the north, and arranging the main structures parallel to the road. The competition received 132 entries from all over Japan, but it was Tange’s entry, symbolically incorporating the dome into the design, that won first place. During the final planning stage, the design was altered to include a cenotaph on the north-south axis.

PHOTO: RIO SHIRAI

A debate had arisen after the war concerning whether to leave intact buildings that had been damaged by the bombing, like the dome, which had been the European-style Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, used for exhibitions, and one of the city’s most famous places. Those opposed to it said that preserving such structures would bring back memories that were already difficult for citizens to forget, but the British Commonwealth Occupation Force’s reconstruction adviser in Hiroshima, Maj. S.A. Jarvie, argued that they should be preserved as tourism resources. According to the Aug. 1, 1948, edition of Hiroshima’s Chugoku Shimbun newspaper, the Hiroshima Tourism Association reflected Jarvie’s wishes by announcing a list of 12 “atomic bomb sightseeing destinations,” including the dome. Jarvie was charged with promoting the Hiroshima Peace Park project, and he visited Tange in 1948, before the competition, to discuss the idea of a memorial hall. No record remains of the conversation, but judging from the fact that Tange’s competition entry incorporated the dome, we may surmise that it found favor with him. By May 1949, Jarvie’s term as reconstruction adviser had ended, making it unclear whether he influenced the selection of Tange’s entry.

Although the debate over whether to leave the Atomic Bomb Dome standing has continued, there is no question that it remains a symbol of peace today, 78 years after the bombing, because Tange symbolically incorporated it into the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

ILLUSTRATION: RYOKO YAMASAKI (INFORAB.)

1: Peace Bridge/Tsukuru

2: West Peace Bridge/Yuku

Completed 1952. Design by Isamu Noguchi. Noguchi, the internationally famous sculptor and designer of light fixtures, tables and other furnishings, struggled with his identity as the son of a Japanese father and an American mother. Initially Noguchi was to design the Cenotaph for the Victims of the Atomic Bomb in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park together with Kenzo Tange, but because of Noguchi’s American citizenship the plan was not carried out. The two bridges on Peace Boulevard, which runs along one side of Peace Memorial Park, are named on Tsukuru (“to create”), representing rebirth, and Yuku (“to depart”), representing death.

Completed 2005. Design by Clara Halter (artist) and Jean-Michel Wilmotte (architect). The French government supported this art installation as part of the Wall for Peace project, which erects walls inscribed with the word “peace” in different languages in cities around the world. The gates were created in prayer for world peace on the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombing.

Completed 1955. Design by Kenzo Tange. Tange’s design for the museum was selected in a 1949 competition. His proposal included three buildings arranged in a line, with the Main Building in the center facing the cenotaph and the East Building to the right, connected by a bridge corridor. At the time, an event hall and hotel not designed by Tange were built to the left, but in 1989 they were replaced by Tange’s International Conference Center Hiroshima, realizing his original concept of three buildings of his own design arranged in a line.

Address: 1-5 Nakajima-cho, Naka-ku, Hiroshima-shi (inside Peace Memorial Park)

Built in 1929 as a kimono shop, this reinforced concrete building has three above-ground floors and one below-ground floor. The atomic bomb severely damaged the concrete roof and caused a fire inside, but the structure survived and has been preserved as an A-bombed building. Since 1982, it has been used as a free rest area and tourist information center in Peace Memorial Park.

Completed 1915. Designed by the Czech architect Jan Letzel, the hall was originally built to display products made in Hiroshima. Only the dome survived complete destruction when the atomic bomb exploded about 200 meters away. It was designated a national historic site in 1995, 50 years after the bombing, and registered as a UNESCO World Heritage cultural site in 1996.

The atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, exploded 580 meters above ground, instantly annihilating the area around the hypocenter with thermic rays reaching between 3,000 and 4,000 degrees Celsius, blast force, and radiation. The present-day address of the hypocenter is 1-5-24 Otemachi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima-shi. It is directly above Shima Hospital. Visitors to the small plaque marking the hypocenter invariably look up at the sky.

Completed 1954. Design by Togo Murano. After the Catholic church where he was serving was destroyed by the atomic bomb, the German priest Enomiya-Lassalle — who himself suffered exposure to radiation — proposed that it be reconstructed as a symbol of mourning for atomic bomb victims and prayer for world peace and friendship. Donations poured in from around the world. In 2006, this cathedral and Kenzo Tange’s Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (1955) became the first buildings built after World War II to be designated Important Cultural Properties by the Japanese government.

Address: 4-42 Nobori-cho, Naka-ku, Hiroshima-shi, Hiroshima Prefecture

Cathedral of Noboricho website: http://noboricho.catholic.hiroshima.jp/

広島市中心部にある“平和の象徴”を訪ねる。

広島平和記念公園は日本を代表する建築家・丹下健三が設計したもので、原爆投下から10年目の1955年に完成した。丹下は高校時代を広島で過ごし、“広島に行けば原爆症で死ぬ“と言われていた1946年、この街の復興計画に関わるなど、元々広島には強い思い入れがあった。

丹下は1949年開催の設計競技でこの公園の設計者に選ばれた。平和大通りから公園に入ると、正面に〈広島平和記念資料館(本館)〉が位置する。この建物のピロティをくぐると正面に原爆慰霊碑があり、その慰霊碑の向こうに原爆ドームが見える。そう、平和記念公園には、1本の軸線が走り、その線上に平和記念資料館、慰霊碑、原爆ドームが一直線に並んでいるのである。

実は街が復興していく過程で、原爆ドームを取り壊そうとする動きもあった。市民感情からするとその保存に反対する声もあり、幾度となく原爆ドームの存続に関して議論が続いた。しかし丹下が広島平和公園の計画にこの建築物を象徴的に組み込んだこともあり、原爆投下から78年経った今も、平和の象徴としてこの広島の地にあると言える。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 23 article list page