February 25, 2022

Frank Lloyd Wright and the Imperial Hotel

A HOTEL’S STORY

COURTESY: IMPERIAL HOTEL

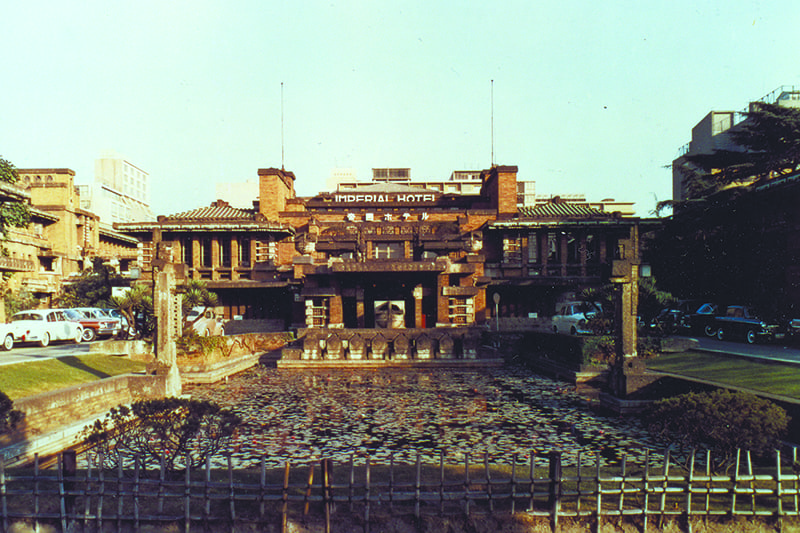

The location is Hibiya, Tokyo, very close to the Imperial Palace. Here stands one of Japan’s leading hotels, the Imperial Hotel. Its founding dates back to 1890, when political and business leaders set out to create a guest house fit for a proud modern nation.

COURTESY: IMPERIAL HOTEL

The hotel’s current building dates back to the early 1970s, but before then the hotel was housed in a palace-like structure, the design of which seemed neither Japanese nor Western. It was the handiwork of master architect Frank Lloyd Wright and was commonly known in Japanese as Raito Kan, the Wright Building.

So how did Wright, an American, come to design Japan’s leading hotel? We’ll start the story there.

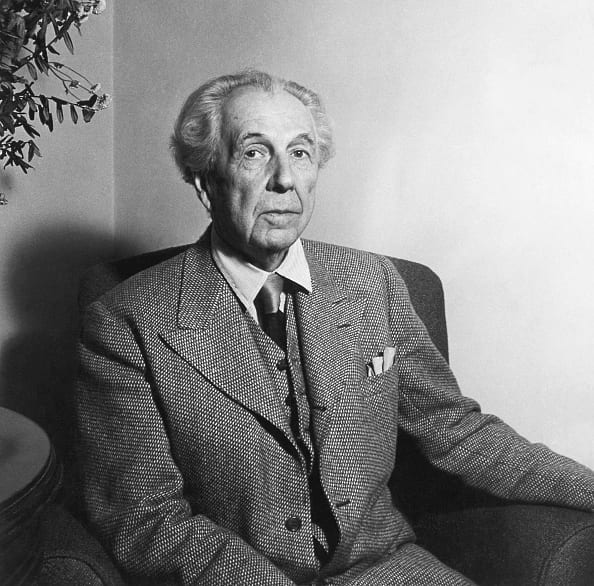

Wright began his career working for architect Louis Sullivan, a leader of the Chicago School. Roughly six years later he established his own office and started creating buildings, mostly houses, that emphasized horizontal lines and were closely integrated with the earth. The work became known as the Prairie School style. But, in addition to being an architect, Wright wore another hat, that of a buyer of Japanese ukiyo-e. And it was this that provided his connection with the Imperial Hotel. When Aisaku Hayashi, who had previously been an Oriental art dealer in New York, was appointed as the seventh manager of the Imperial Hotel, he tapped his old ukiyo-e dealer acquaintance Wright to design the new building.

COURTESY: IMPERIAL HOTEL

At the time, Wright’s jobs in the United States were drying up, after several high-profile scandals involving his personal relationships. For the architect, the Imperial Hotel job in Japan no doubt appeared like a chance at redemption. In it, he set about creating a new type of architecture fusing East and West, ancient and modern. The symmetrical appearance of the guest room wing was reminiscent of the first Japanese architecture that Wright had encountered: a re-creation at the 1893 Chicago Expo of the Phoenix Hall from Byodoin Temple in Uji, Kyoto. The low-lying building is firmly planted in the ground, as in the Prairie School style, and the building is clad in Oya (a gray-green lava stone mined in Tochigi Prefecture near Tokyo) with a geometric pattern similar to a Maya ruin. This amalgam was born from Wright’s insistence on not making copies of existing Western architecture. However, the strength of that passion was also his undoing. Due for completion in 1921, the building faced significant delays, and costs almost doubled from the original budget. Hayashi defended Wright, but in April 1922, when the original building burned to the ground in an accidental fire, he ended up resigning as manager. Having lost his major backer, Wright returned to the United States three months later and never returned to Japan again.

Along with Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright is considered one of the three masters of modern architecture. Born in Wisconsin in 1867, he designed over 800 buildings during his lifetime. His best-known works include Fallingwater (1937) and the Guggenheim Museum (1959). In Japan, in addition to the Imperial Hotel entrance (1923), which has been relocated and restored in Aichi Prefecture, his extant buildings are Jiyugakuen (1922) in Tokyo and the Yodoko Guest House (1924; formerly the Yamamura residence) in Hyogo Prefecture.

© BETTMAN/GETTY IMAGES

The hotel job was taken over by Wright’s disciple Arata Endo and was successfully completed in 1923. On the day of the opening reception, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck, but Wright’s unique construction method, which he called a “floating foundation,” which shortened the foundation piles to absorb vibration, proved effective on Hibiya’s soft ground. The building was unharmed, and Wright, who was by then back in the United States, proudly played up the seismic resistance of his architecture in his autobiography. The Imperial Hotel was known as the “Pearl of the East” and went on to entertain many guests as one of Japan’s leading hotels. The building survived the Pacific War, and during the postwar Occupation was even requisitioned for use by the Allied Occupation forces.

We then jump forward to March 1967, when Japan was at the height of its rapid economic growth. With newspaper reports suggesting the old hotel would be rebuilt as a high-rise, a movement to secure its preservation was born. At its center was the Imperial Hotel Preservation Association, comprising Japanese architects who also lobbied politicians such as Prime Minister Eisaku Sato for the hotel to be preserved. In October 1967, Wright’s wife, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, visited Japan to lend her support to the movement, and what was rapidly becoming a bilateral U.S.-Japan issue was even debated in the Diet.

COURTESY: IMPERIAL HOTEL

But although it was only 44 years old, the building was deteriorating badly. The floating foundation construction that had protected it from the earthquake was also a liability, causing the building’s foundations to gradually subside. Just before the building was ultimately demolished, the first-floor office was already half underground, and the corridor of the guest wing was so buckled that trolleys could not be used. The hotel management remained focused on economic considerations and firmly committed to rebuilding. After much back-and-forth, it was decided that the hotel’s entrance would be relocated and restored at Museum Meiji Mura in Aichi Prefecture. Meiji Mura was reluctant to take on the responsibility because of the huge cost, but after discussions between its first director, architect Yoshiro Taniguchi and Prime Minister Sato, it was decided that the government would support the project.

And now, 50 years later, one can stand in Hibiya Park, looking across at the current building, and imagine what it would be like if even just the entrance of the old Wright Building were still in place. Go inside to the second floor and squint hard enough at the mural from the old building that adorns the hotel’s Old Imperial Bar, and you might just get the feeling that you are in the old building. Meanwhile, the main building of another grand hotel, the Hotel Okura Tokyo, which was completed in 1962 by Taniguchi, went through a similar process — closing in 2015, becoming the subject of international calls for its preservation and then eventually being demolished and rebuilt in 2019. In that case, only the former lobby area was retained and restored. While one hopes that Japan finds other ways to address architectural preservation beyond scrapping and rebuilding, the tale of the Imperial Hotel shows just how hard it can be to preserve a building while it remains in use.

建築家F.L.ライトと、帝国ホテルを巡る物語。

東京·日比谷に日本を代表するホテル、帝国ホテルが建っている。創業は1890年。近代国家を目指す日本の「迎賓館」の役割を担う場として、政財界人らの働きかけによって生まれたホテルである。現在の建物は1970年代のものだが、その前は独特のデザインをした宮殿のような建築が建っていた。それがフランク·ロイド·ライト設計の今は無き、通称ライト館と呼ばれる建物だ。

時は日本が高度成長の絶頂期にあった1967年。新たな高層ホテル建設が報道されると、ライト館保存運動が展開される。ライトの妻オルギヴァンナも保存活動のために来日し、取り壊しは国会でも取り上げられた。だが建物は、完成から44年しか経っていないのに老朽化が進んでいた。建物の地盤沈下が激しかったのだ。

議論の末、玄関部分のみが愛知県の〈博物館明治村〉へ移築·復元されることとなった。移築には莫大な費用がかかるため明治村も難色を示していたが、初代館長である建築家·谷口吉郎と佐藤栄作首相が面会し、政府協力のもと移築を進めるということで受け入れが決まった。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 9 article list page