October 28, 2022

Mika Ninagawa: Expressions of vivid transience

ARTIST / FILM DIRECTOR

COURTESY: MIKA NINAGAWA

MIKA NINAGAWA

Focusing primarily on photography, Ninagawa has created many films, videos and spatial installations. Among the many awards she has won is the Kimura Ihei Award. In 2010, Rizzoli New York published a book of her photographs. Ninagawa has made five feature films, including “Helter Skelter” (2012) and “Diner” (2019), and also directed the Netflix original series “Followers.” Her most recent photo book is “Mika Ninagawa: A Garden of Flickering Lights.” Her major solo exhibitions encompass “Mika Ninagawa” at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Taipei (2016), the traveling exhibition “Mika Ninagawa: Into Fiction/Reality,” which visited a number of Japanese art museums (2018-2021), “Mika Ninagawa: Into Fiction/Reality” at the Beijing Times Art Museum (2022) and “Mika Ninagawa: A Garden of Flickering Lights” at the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum (2022). Her website is https://mikaninagawa.com.

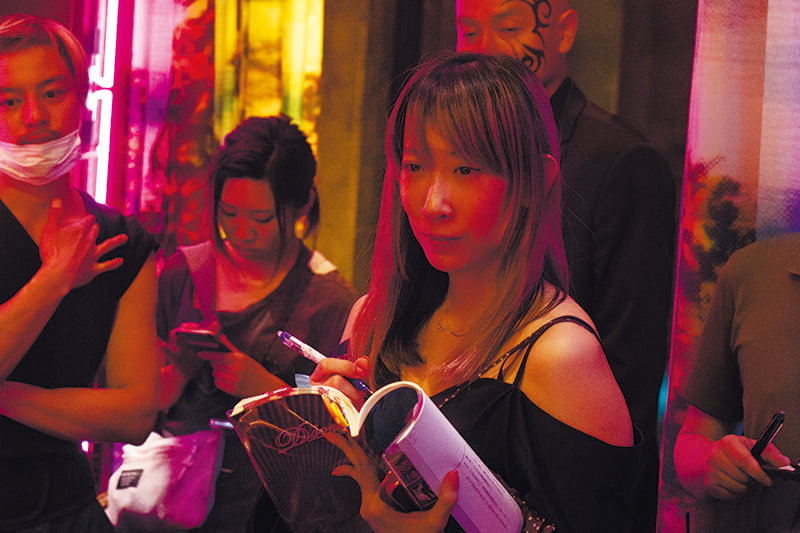

© MIKA NINAGAWA / “DINER” FILM PARTNERS

Mika Ninagawa has won the acclaim of a wide-ranging audience as one of contemporary Japan’s leading photographers and film directors. She consistently captures intense yet ephemeral moments of life, like sparks of vivid color.

The daughter of eminent stage and film director Yukio Ninagawa, she has been driven since early childhood by a desire bordering on obsession to prove herself as a person in her own right, not merely Yukio Ninagawa’s daughter. While outrage long was the motivating force behind her creativity, a dramatic change has taken place in her inner landscape over the last few years, she says. How did she start taking the photographs that established the name of Mika Ninagawa, and what direction does she now intend to take in her expressive work? We talked to her at her Tokyo studio.

“Since I was very young, I’ve wanted to find the answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ I think one influence was growing up in an unconventional family environment, with a director for a father and an actress for a mother,” she said. “I well remember the momentary excitement I felt as a first-year undergraduate, studying graphic design at an art university, the first time one of my photographs was chosen for inclusion in an exhibition open to submissions from the public and I was called an artist. I felt as though I’d been liberated from something at last.”

For Ninagawa, being a photographer was perhaps not simply an occupation, but the best means of expressing what was inside her, so she could become herself.

“In the world of photography in the mid-1990s, when I started out, shots so out of focus that you couldn’t tell what was depicted were anathema. When I won a major prize, even though my exhibition attracted the highest-ever number of visitors, I was dogged nonetheless by hurtful comments about my shots being out of focus and that they didn’t even deserve to be called photographs.”

Talking about this memory, she revealed her highly sensitive side as an artist.

Outrage was the motivating force behind what she expressed, Ninagawa said. At the root of this anger was the atmosphere in Japan at the time.

“I was furious about the inequality between men and women, about the idea that you couldn’t do certain things or had to put up with being told certain things because you were a woman. I want to be an artist who creates work with breadth, that anyone can access, rather than producing pieces for a limited range of people, such as a handful of art lovers or the wealthy. However, audiences sometimes reject my work before even actually seeing it. That’s the difficulty of producing expressive work for the public, and I have a kind of love-hate relationship with it. Now I think it’s fine just to enjoy my life without digging my heels in about it. But when I was young, I was cursed by the idea that I mustn’t enrich my lifestyle or be satisfied or happy,” she said with a laugh.

Ninagawa’s photographic works are often a mixture of the fictional and the real. For example, some of her works feature photographs of artificial flowers. Why does she choose to take pictures of artificial flowers rather than real ones?

COURTESY: MIKA NINAGAWA

“From my early childhood, because I lived in a home with a director for a father, who lived in the worlds of both fiction and reality, I thought that was just the way the world was. I’ve shot artificial flowers in the sense of something fictional. While they’re fake flowers, I see them as having taken shape from someone’s desire to create flowers that won’t die. I often shoot artificial flowers left as offerings on graves in Mexico and other hot countries. When I feel the emotions inspiring people to leave offerings to the dead of flowers that won’t wither, there is a moment when they look even more beautiful than the real thing. I feel that fictitious doesn’t equal fake.”

The photographs in the recent exhibition “Mika Ninagawa: A Garden of Flickering Lights” at the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum all featured fresh flowers. She says it was only after she had finished taking the photographs that she realized all the flowers were in places created by someone to display flowers, such as a flower bed, garden, avenue of cherry trees or flower park. Over the last few years, something in Ninagawa has changed. She says she began to feel there were limits to what she could express when motivated by anger alone. And Ninagawa herself was startled by the change that occurred as her anger melted away.

“I’m powerfully drawn to the ephemeral and the momentary, to things that sparkle for a fleeting instant. The pandemic has made us all realize that nothing lasts forever, and that’s exactly why things with a transient delicacy — like flowers blooming at the roadside or a ray of sunshine on a warm, sunny day — that melt away in a moment are so lovely. It’s that feeling of wanting that precise moment to last forever, of wanting to look at it for the rest of time, that makes me press the shutter button. I’ve recently become clearly aware that that’s a key part of my motivation to create things.”

The principal catalyst for her change of heart emerged back in 2016, around the time she was faced with the loss of her father.

“Perhaps I was looking at the world through my dying father’s eyes. Scenery I’d seen before looked totally different. It was then I started focusing more on the world’s splendor. I realized how wonderful it was to be alive, and that momentary radiance contained a number of glorious emotions. I decided that, while my life might be snuffed out one day, I wanted to live my life to the fullest in the here and now. For the first time in my life, I thought it would be fine to express myself by focusing on wonderful things. I embraced my feeling that flowers and light are beautiful and photographed them. I’d also given birth to my second child, and for the first time, I allowed myself to be happy and to bask in the euphoria of being a mother.”

COURTESY: MIKA NINAGAWA

Ninagawa also began to experience another change. Since early childhood, the artist had been searching for herself and the reasons why she was here, but recently she has come to discuss such matters from the viewpoint of “we,” rather than “I.”

“It took me all these years, until I began to put together a team to make a film, to discover how enriching it is to create something with other people. While the presence of a director is an absolute necessity in making a film, we always discuss everything together. Blending ideas and resonating with each other as we create something is a wonderful feeling. I hadn’t realized how much fun playing in a band could be!” she said, laughing. “I’ve now switched from talking in terms of ‘I’ to ‘we,’ and I feel as though something new might emerge.”

Soon to celebrate her 50th birthday, Mika Ninagawa calls this the halfway mark in her life. Her desire to express herself remains unstoppable. We are extremely lucky that we will be able to encounter her new forms of expression, now that she has shaken off the curse of anger being her driving force.

蜷川実花の作品がもつ、鮮烈な色彩と儚さの秘密。

現代日本を代表する写真家、映画監督として幅広い層から支持される蜷川実花。彼女が捉え続けるのは鮮烈な色彩がスパークするような、激しくも儚い生の一瞬である。

蜷川実花は演出家、蜷川幸雄の長女として生まれ、幼少期から著名演出家の娘ではなく「私自身になる」という強い意志で、大学在学中に写真家としてデビューを果たした。以来「怒り」を創作の原動力にしてきたという。

そんな彼女から見えてきたのは、いたってセンシティブな表現者としての横顔だ。「怒り」のルーツは、男女の不平等、作品を見る前から否定してくるパブリックに向けて表現していくことの難しさ。蜷川は「表現者は幸せであってはいけない、という呪い」を自身にかけていた。

そんな蜷川が変わるきっかけは2016年頃、父を失う時期に起こった。「亡くなっていく父の目線」で世界の異なる風景を見、瞬間の輝きを捉える経験をした。「人生で初めて、素晴らしいものにフォーカスして表現していいのだ」と感じた蜷川。彼女の新たな表現とこれから出会うことができる私たちはとても幸運だ。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 17 article list page