March 24, 2023

On 100th anniversary of the Great Kanto Quake

EARTHQUAKE

The magnitude 7.8 earthquake that struck southern Turkey on Feb. 6, killing more than 50,000 people there and in neighboring Syria, is still fresh in memory. For many people, the threat of a large earthquake that could strike at any time is a constant source of fear. And the chance of a major one occurring directly below the Tokyo metropolitan area within 30 years is estimated at 70%.

https://www.bousai.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/1002147/1008042/1008046/index.html

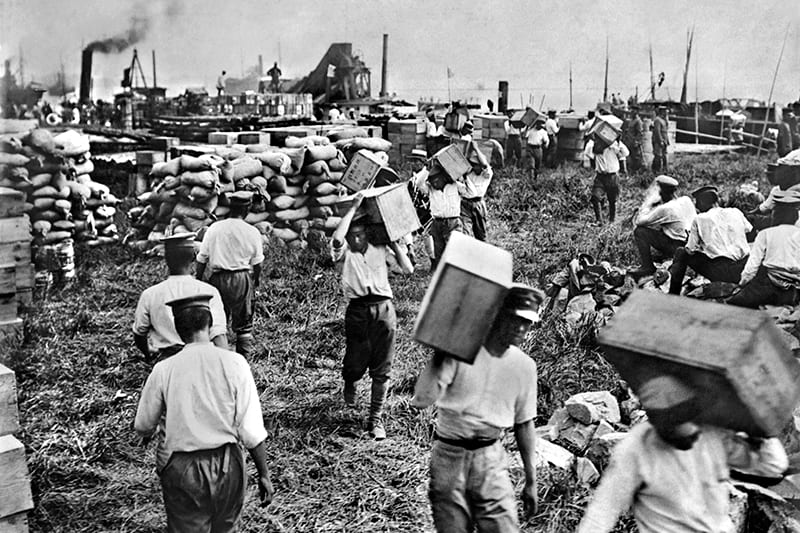

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 was the most devastating earthquake in Japan’s modern history. More than 105,000 people died or were never found, and 300,000 houses were destroyed either by the tremors or by fires. Lifelines such as electricity, water, roads and railways were severely damaged. The capital city of Tokyo and the port city of Yokohama, where many foreigners lived, suffered massive damage, and the social impact was enormous. This year marks the 100th anniversary of those tragic events.

The weather in Tokyo was sunny at 11:58 a.m. on Sept. 1, 1923, when an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 7.9 struck off the coast of Kanagawa Prefecture, with its epicenter in the northwestern part of Sagami Bay. The worst part was that the earthquake happened during lunchtime and strong winds were blowing. Families were in the middle of preparing meals over open flames in hearths and charcoal grills, so the strong shaking caused dozens of fires and the winds caused them to spread quickly. In Tokyo, the situation was compounded by the fact that people had time to start evacuating. They loaded household possessions such as futons on large eight-wheeled carts — but then the fires spread to their belongings. Tens of thousands fled to a large open space at the military clothing warehouse in Honjo (now the Yokoami area in Sumida Ward), where a fire tornado soon formed, killing about 40,000 people.

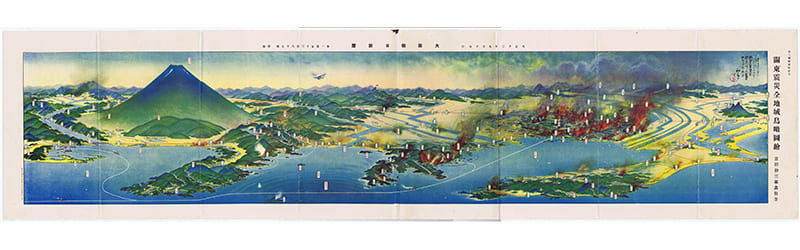

COURTESY: TOKYO MEMORIAL HALL OF RECONSTRUCTION

In the southern part of the Kanto region, especially in western Kanagawa and Chiba Prefecture’s Boso area, landslides were triggered by the earthquake and the heavy rain that followed. One landslide alone killed 406 people. In addition, tsunamis occurred along the length of Sagami Bay, from Hayama and Kamakura to Shimoda on the Izu Peninsula, and on the southern tip of the Boso Peninsula. They reached heights of 12 meters in Atami and 9 meters in Tateyama.

Using its experience with the Great Kanto Earthquake and other large earthquakes, Japan has taken various countermeasures over the last century. The Building Standards Act was enacted, introducing particularly strict rules with regard to fire and earthquake resistance. Roads were widened, areas were cleared of high densities of wooden buildings, green open spaces were established and urban planning based on disaster prevention was promoted. Partly because of these efforts, some people believe that even if an earthquake on the scale of the Great Kanto Earthquake occurred now, the damage would not be so great.

COURTESY: TOKYO MEMORIAL HALL OF RECONSTRUCTION

Under such circumstances, in 2022, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government reviewed for the first time its 2012 publication estimating damage to Tokyo due to an earthquake directly below the capital and its 2013 estimate of damage due to a major quake along the Nankai Trough. Both documents were originally based on the Great East Japan Earthquake. According to the first one, if a magnitude 7 earthquake occurred directly under the southern part of the city center on a winter evening with a wind speed of 8 meters per second (a fresh breeze of 29 kph), an estimated 194,431 buildings would be damaged and 6,148 people would die.

There are many things individuals can do to prepare for major earthquakes. For example, evacuation simulations. If you encountered an earthquake while at work or school, which route would you take to get home? Where would you meet your family? How would you communicate? It is also important to prepare food, water, batteries and charging equipment that can be used in the event of a disaster. It is even more reassuring to have close friends, acquaintances and family members nearby, and important to communicate with those neighbors on a daily basis.

While the top priority during a major earthquake would be to survive the initial shaking, it is also worth remembering that lifelines such as electricity, gas and water would probably fail. And although you might think they would be restarted after a few weeks, it could take a lot longer after a major quake. We might not be able to use our homes’ toilets and showers for several months. The lifestyles we all take for granted could be changed completely. There is a Japanese proverb that says, “If you make the preparations, then you don’t have to worry.” And the first step in making preparations is to learn the lessons from the past and imagine what might happen in the future.

COURTESY: TOKYO MEMORIAL HALL OF RECONSTRUCTION

COURTESY: TOKYO MEMORIAL HALL OF RECONSTRUCTION

「関東大震災」から100年。その過去から何を学ぶのか?

2月6日にトルコ南部で発生したM7.8の地震は、隣国シリアと合わせ5万人を越える犠牲者を出す大災害となった。日本の近代史上、最も被害を出した地震は、1923年に発生した関東大震災である。死者・行方不明者は10万5,000名以上、焼失を含む全損家屋も30万戸に上った。

2022年、東京都は、東日本大震災を踏まえ策定した被害想定を10年ぶりに見直した。M7クラスの地震が冬の夕方、首都直下で発生したと仮定した場合、建物被害は19万4,431棟、死者は6,148人に及ぶと想定している。地震発生後は電気・ガス・水道といったライフラインが機能しなくなる。長いと数週間以上、もしかしたら数か月に渡って、トイレも使えず、シャワーを浴びられない生活が続くかもしれない。そうなると今まで当たり前に過ごしていた生活は一変するだろう。

日本のことわざに「備えあれば憂いなし」というものがある。前もって準備をしておけば、いざという時に何が起こっても心配無用という意味だ。100年前の「関東大震災」を教訓に想像力を働かせ、大地震に備えたい。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 22 article list page