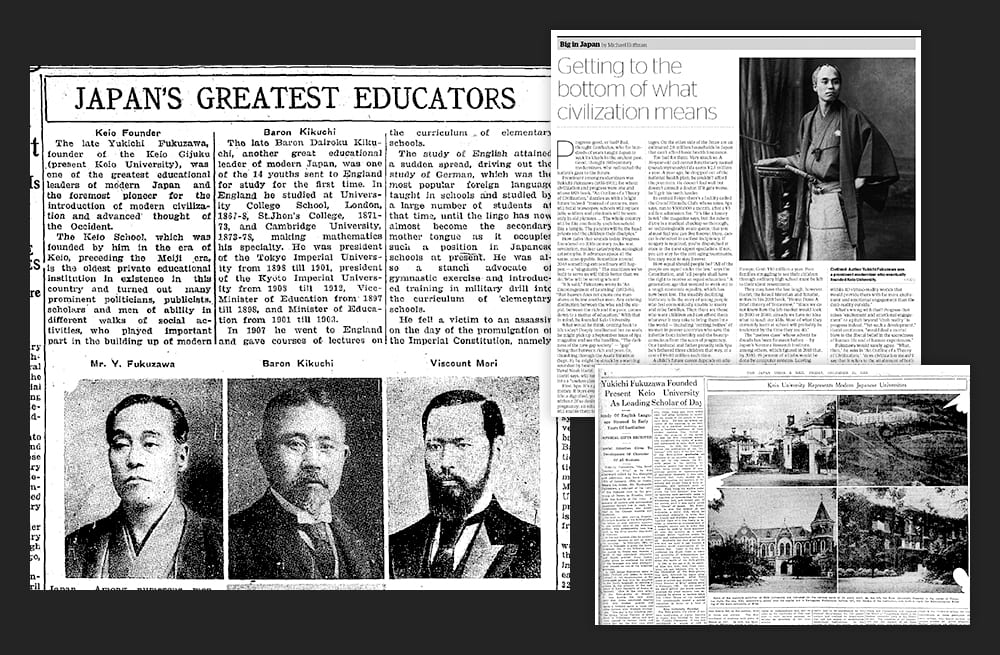

February 21, 2025

Showing diversity is the best part of being an artist: Aki Inomata

ART

COURTESY: MAHO KUBOTA GALLERY

PHOTO: TAKAO OHTA

From a hermit crab in a beautiful transparent shell to a wooden sculpture carved by a beaver, contemporary artist Aki Inomata’s creations are often the result of collaborations with animals. But their message runs deeper than cute creatures — they pose questions about social systems and our preconceived notions.

Take, for example, “Why Not Hand Over a ‘Shelter’ to Hermit Crabs?” Hermit crabs have a habit of moving to new, more comfortable homes as they grow bigger. Inomata measured the internal structure of shells that the crabs have inhabited using a CT scan, then generated 3D computer graphics of the structures and reproduced them using a 3D printer. She then topped off her shells with models of landmark architecture from cities like New York City, Paris, Hong Kong and Tokyo. Her videos of hermit crabs moving from one “city” to another may overlap in our minds with shots of migrants or refugees we might see in the news. The work makes us think about the nature of human identity, appearance and nationality.

© AKI INOMATA / I Wear the Dog’s Hair, and the Dog Wears My Hair,2014

The works in the series were first made for the exhibition “No Man’s Land” (2009), which was held at the French Embassy building in Tokyo, which had been earmarked for demolition. The building was demolished in 2009, and a new embassy was built on adjacent land. The land where the former embassy was located was technically part of France until October 2009, after which it was leased back to Japan on a fixed-term lease for 60 years and then will be returned to France. In other words, the land stays the same, and yet its country changes. Similarly, the hermit crab remains the same while the “country” it carries on its back changes. Inomata’s work identified a common denominator in two very different things.

Another of her works that leaves a strong impression is “How to Carve a Sculpture,” which uses wood carved by beavers. Inomata asked five zoos to allow her to set up short wooden beams in their beaver breeding areas. After the beavers had gnawed through the wood she collected it, and she found it was beautiful in a way similar to human-made sculptures. She then used a professional sculptor and a carving machine to create dual replicas on a human scale, three times the size of the originals. In other words, the beavers’ creations were imitated by humans and machines. So, is the artist of the resulting work man, machine or beaver?

In Inomata’s “Why Not Hand Over a ‘Shelter’ to Hermit Crabs?” (2009-), she used CT scans to measure shells, replicated them using a 3D printer and added models representing Paris, Tokyo and other cities. Hermit crabs moving between “cities” suggests migrants or refugees and makes us reconsider the nature of human identity and nationality.

©AKI INOMATA / Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs? -Border-(2009-)

“I am interested in the creativity possessed by living things. For example, beavers make dams and lodges using tree branches to store water, impacting their surrounding environment. I started by researching such habits. My focus was on wood that had been gnawed by beavers, but I realized the marks left on the wood were like those left on wooden sculptures by humans. In a sense, the beaver was the artist. However, it was also possible that the forms were the result of the beaver avoiding the harder parts of the wood, like knots. If so, then perhaps it was the tree that was the artist, because the tree creates its own form. If so, then who or what should be seen as the subject (in other words, the artist) of the creative act? I think this series makes us think about those questions,” she explained.

What she hopes to explore through her artwork is “a worldview in which humans are not just thinking about themselves.” During her time in college, her first topic of interest was connecting with the natural environment.

“Born and raised in Tokyo, I didn’t have much exposure to the great outdoors, so at the time I was creating works that brought natural phenomena into the exhibition space. The work I created for my graduation project at Tokyo University of the Arts was about digitally controlling natural phenomena. I projected ripples of water and dripping rain onto the floor. However, I felt that kind of work replicated the things I felt uncomfortable about, like the exertion of control over nature and the expulsion of living things from urban society. So then I thought, why not create works in collaboration with another being over whom I have no control at all? It was from this thought that the hermit crab work was created for the exhibition at the French Embassy in Tokyo in 2009,” she said.

Finally, we asked her if she has ever felt disadvantaged by her gender, either as an artist or as an individual. Noting at first that she does not think about the issue in terms of benefits or disadvantages, she expressed her belief that as an artist she can “show diversity.”

“I believe that the best part of being an artist is to broaden people’s worldviews and values by showing diversity through your art. In my case, the theme of my work is the diversity of living things, not only in the human world but also in the natural world, and also the idea of undermining anthropocentric thinking. Every artist will appeal to a slightly different audience, but what they all have in common is a desire to expand perspectives on the world without being constrained by preconceived notions. I believe that by broadening our worldview, we can create a way of thinking that recognizes diversity and helps create a society that is easy for individuals to live in.”

©AKI INOMATA / How to Carve a Sculpture,2018- / Photo: Naomi Ito, Production Assistance: Izu Shaboten Zoo

©AKI INOMATA / Mutual Aid. Art in collaboration with Nature 31,Oct 2024 – 23 Mar 2025, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Photo:Sebastiano Pellion di Persano

AKI INOMATA

Contemporary artist born in 1983. Graduated from the Department of Inter Media Art at Tokyo University of the Arts in 2008. Lives and works in Tokyo. Inomata presents things born from or through collaboration with nonhuman creatures or nature. She has exhibited many works created in collaboration with living creatures, like “Think Evolution,” a work in which an octopus encounters an ammonite, thereby bridging millennia of evolutionary distance. Her work is included in major collections such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Art Gallery of South Australia, the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto and the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art. https://www.aki-inomata.com/

芸術家の醍醐味は、多様な考え方を広げること。

かわいらしいヤドカリが美しい透明の貝殻に入った作品や、ビーバーに削らせた木を改めて仕立て直し彫刻作品にしたりと、現代美術作家AKI INOMATAが生み出す作品は動物とのコラボレーションの賜物だ。だがその愛らしい生き物たちを用いた作品の根底には、人間社会が作り出す仕組みや既成概念への問題提起がある。彼女が芸術作品を通じ探求していきたいことは、“人間が人間のためだけを考えていくのではない世界観”だという。

「アーティストは作品を通じ多様性を示すことで、人々の世界観や価値観を広げていくことが醍醐味だと思っています。私の場合は、人間界だけではなく自然界も含めた様々な生き物の多様性や、人間中心主義を変えていこうということが作品づくりのテーマになっています。アーティストが訴えるものはそれぞれですが、共通しているのは既成概念にとらわれず、世界観を拡張していこうとすること。世界の見方が広がっていくことで、多様性を認めるような考え方が生まれ、個人が生きやすい社会をつくる一助になっているのではと思います」。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 45 article list page