October 22, 2021

Toshiko Mori’s architecture stands for the future

ARCHITECTURE

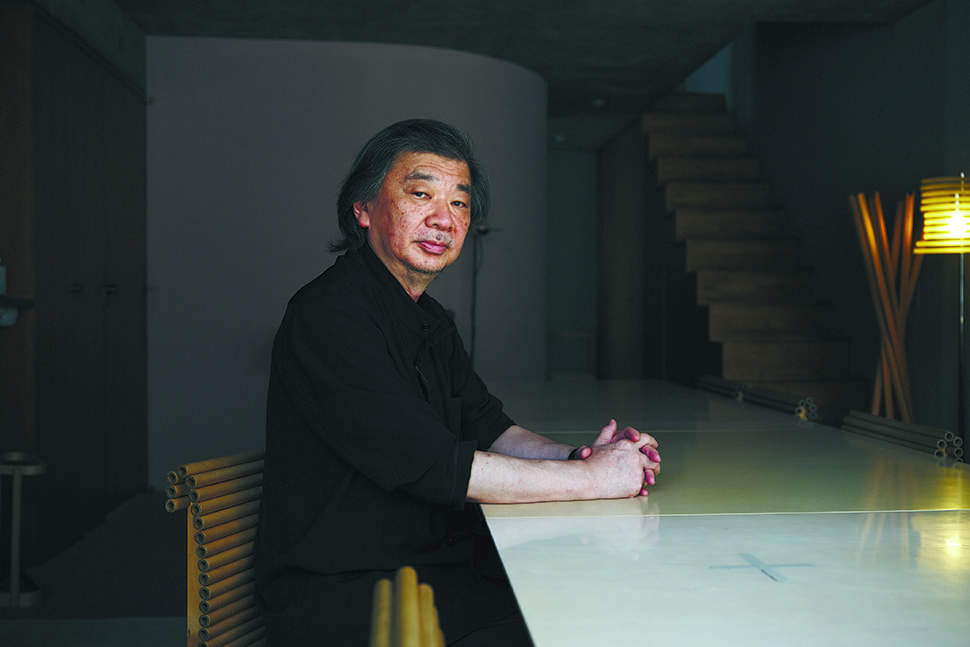

TOSHIKO MORI

Toshiko Mori was born in 1951 in Kobe. She graduated in 1976 from the Cooper Union School of Architecture. She is the founding principal of Toshiko Mori Architect PLLC. She received an honorary master’s in architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1996, became its first female tenured faculty member and today serves as the Robert P. Hubbard professor in the practice of architecture. Her awards include the Academy Award in Architecture, from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; the AIA New York Medal of Honor; the 2016 ACSA Tau Sigma Delta National Honor Society Gold Medal; the AIA/ACSA Topaz Medallion for Excellence in Architectural Education; Architectural Record’s Women in Architecture Design Leader Award in 2019; the Louis Auchincloss Prize, from the Museum of the City of New York; and this year, the Isamu Noguchi Award, from the Isamu Noguchi Foundation. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

There is almost never a time when we are not aware of architecture, even if only subconsciously. Each time we climb a staircase we encounter a marvel of architectural design that we are so used to, we don’t give it a thought. In school we may learn the three conditions that the Roman Vitruvius set out as the intent of architecture: “firmness, commodity and delight.” The first two simply require that the building not fall down and also be useful. It is the third that beckons us to ask what fulfills us in life. Is an architect one who creates pretty baubles — a staircase that takes us from here to there — or a path on which civilization ascends?

New York-based architect Toshiko Mori’s postwar childhood memories aren’t weighted with bitterness, but tinged with youthful hope. No matter one’s station before, the war was a great equalizer. All shared the destitution, the scarcity. She learned to protect and preserve the little there was, to farm vegetables with her grandmother, to raise chickens. And as a teen, when time set Japan back on its feet and her father’s work took the family to New York City, she carried that hopefulness with her and found it manifested in the city’s diverse cultural and professional experiences. “It fit me well,” she said. The exposure to new avenues she found “broader, in terms of challenges, than staying in Japan. I thought I could be independent here, be my own person.”

When her parents moved on she chose to stay, enrolling in Cooper Union, where she studied architecture under fabled teacher and architect John Hejduk, who instilled the belief that architecture obligates the practitioner to enter a sort of social contract, carry their knowledge to the next generation and help those younger with the first step on a climb to self-realization. So she taught at Cooper Union for 14 years. She taught at Yale; she directed the Harvard Graduate School of Design for another half-dozen years; she teaches to this day. She founded her own architectural practice in the early 1980s, through which she has developed a stunning portfolio of residential, commercial and institutional architecture and is renowned for addressing the work of past masters like Frank Lloyd Wright, Paul Rudolph and Marcel Breuer — supporting the original structures, engaging them, enhancing them, amplifying the brilliance of what preceded her there.

Through an association with the Albers Foundation, the architect came to work in eastern Senegal, one of the remotest regions of Africa and a place where she had never considered building. She had been selected to work on the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum’s 2004 exhibition “Josef and Anni Albers: Designs for Living,” the posthumous first joint exhibition of the couple’s work. Painter Josef Albers was revered as a teacher from the Bauhaus to Yale. His wife, Anni, made art in print and textiles. The latter medium held a connection — a thread, if you will — to Mori, whose career is marked by an intimate relationship with materials and their use, textiles holding a prominent place among them. (Her 2002 release “Immaterial/Ultramaterial: Architecture, Design, and Materials” remains among the most advanced studies of the topic to date.) Refugees from Nazi Germany, the Alberses knew scarcity and the destruction of comfort and culture it engenders. They formed a foundation, centered on Josef’s dictum “minimum means for maximum effect,” that would address these problems where the need was most profound.

The Senegalese region of Tambacounda, where the village of Sinthian is located, suffered the worst lack of medical resources and the highest rate of infant and maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. A quarter of a century of developing successful clinics and kindergartens there has reversed those trends today, and in those efforts Mori saw an opportunity to introduce her students to the dynamics of building toward the cause of social betterment. She independently raised funds to conduct visits with her class in 2010 and 2012, and through these investigative expeditions it was recognized that Sinthian held immense potential for reviving the region if the dozen or so local tribes could align their collective skills and energies toward mutual ends. A public gathering place where art and ideas could be shared and broadcast would thrust such a movement forward, and in collaboration with the foundation, the Thread Artists’ Residences & Cultural Center was born in 2015.

In building it, commitment to the community merged with sheer necessity. There was neither the money nor the means to bring in building crews and materials. Every compressed earth brick, every shaft of grass in the thatched roof would have to be made or obtained locally, and the building would be raised and maintained by local crafters, working on instruction from the architect.

“I had no choice,” Mori said. “My challenge was to make architecture out of materials and of a typology that exists. … There’s incredible wisdom in the African hut structure that hasn’t been explored.” She offers as an example the stack effect, which raises hot air through the porous thatched roof, drawing in cooler air through apertures in the brick closer to the ground. The result is that without a powered cooling system, the temperature inside the public structure may be 10 degrees Celsius lower than the surrounding terrain, which lies directly on the equator. Minimum means, maximum effect. The roof is, in fact, Thread’s masterstroke. Senegal is arid two-thirds of the year, and it rains the rest of the time. The architect’s analysis showed that a single season’s rain could sustain the area for the entire year. So she designed the roof to guide rain into troughs and collect it in cisterns, to be used for washing and planting year-round.

Thread became a gathering place, a learning place, a unifying place and, through the sale of now-viable crops, an economic driver to boot. This gave rise to a startling development. People in the far more conservative nearby village of Fass did something experts on the region insisted they never would: They came to the group and asked for an elementary school. “Illiteracy and poverty are a lethal combination,” the architect said. “Kids are enlisted into terrorism because they’re signing things they can’t read and believing things they can’t verify.” Local elders understood this, but it still took three years of intense negotiation to ensure that the 2019 Fass School and Teachers’ Residence, which can educate 300 students ages 5 through 10, would teach the pedagogical fundamentals alongside the Quran and serve girls alongside boys — previously unimaginable. Children clamor to attend, and why wouldn’t they? Architecturally related to and equally rigorous as Thread, the building is cool and quiet inside, unlike traditional local schools, where students suffocate in airless enclosures with metal roofs under which they bake most of the year, and deafening rain makes teaching impossible for the rest. The building’s eaves give respite from blinding sunlight, permitting kids to sit outside and read. The building is circular, invoking the comforting social presence of the traditional tribal homestead, an oasis of calm, joy and safety.

Those who see food insecurity, resource scarcity and climate change as isolated silos of imminent crisis, the architect feels, are misunderstanding their meaning. “There’s no one answer,” she insisted. “One needs to attack, all at once, issues of water, energy use, food production and also issues of social justice. Those issues are huge. There is a tendency to look only at numbers. Quantifying without understanding connected issues and impacts to the human communities and environment is dangerous.”

We returned to the question of how she views the architect’s less-heralded mandate to build more than commodities in the world, and she offered an observation. She has built in countries where architecture revolves around a mortgage cycle, and others where it must endure as long as possible. In eastern Senegal, few give much thought to architecture or what an “architect” is. An individual is regarded by the value they bring to everyday experience. The kids understand what she’s done, and call her simply “Toshiko.” That, she says, is exactly the way she likes it.

建築家・森俊子が創り出す「建築の彼方(かなた)」。

セネガル南東部に設立された「スレッド」は、村人同士、そして芸術を通じて海外との相互交流を目指す文化センターだ。

地の利が悪く、物資の乏しい僻地のため「あるものだけで」建てねばならない。茅葺き屋根に日干しレンガの壁。地元の材料を使い、村人自身の手で建造・修復できる建物に。優美なスロープを描く屋根は雨水を集め、通気性が高いため炎天下でも内部を涼しく保つ。これで生活用水の30%がまかなわれ、続いて設立した「ファス小学校」でも快適な学習空間が生み出された。

設計は森俊子。米国内外で教育機関や住宅、美術館など多数手がける建築家だ。教育者としての功績も長年に及び、建築学部長を6年間務めたハーバード大学で現在も教鞭を執る。原点の一つは神戸で過ごした幼少時代。戦後の食糧難の中、祖母の家庭菜園や鶏の世話を手伝った。物が無いゆえの創意工夫や知恵、他者や異文化に対する敬意に基づく発想力。その精神はセネガルそして世界の次世代へといま豊かに拡がるのである。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 4 article list page