November 29, 2024

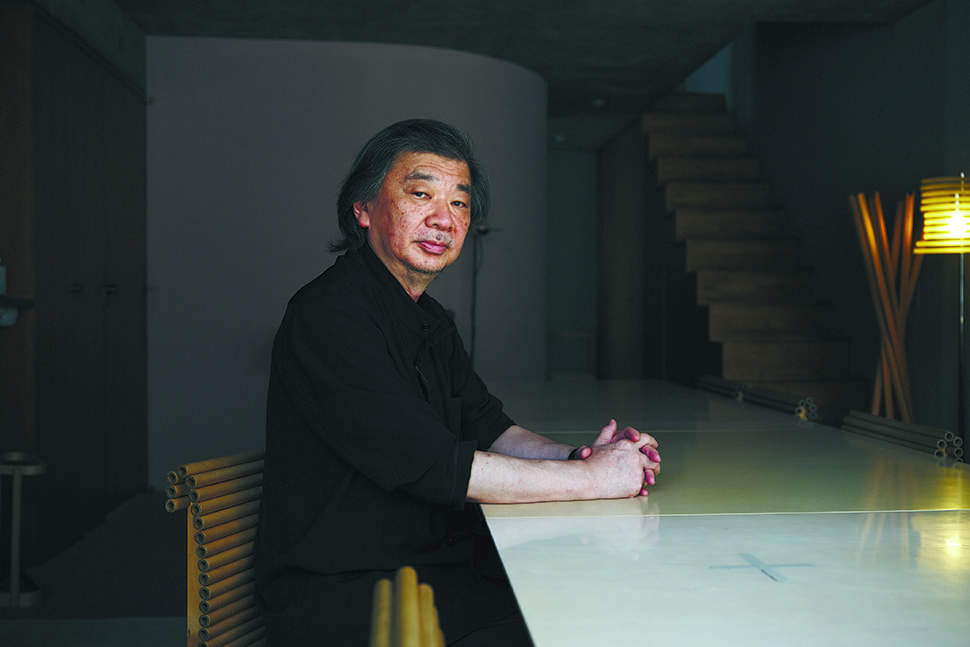

Riken Yamamoto explores spaces that foster community

INTERVIEW

PHOTO: YOSHIAKI TSUTSUI

Among the many international awards for architecture, only one is known as the field’s “Nobel Prize”: the Pritzker Architecture Prize, established in 1979 and sponsored by the Hyatt Foundation in the United States.

The award is given each year, usually to just one architect, in recognition of “consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.”

The winner of the 2024 award was named on March 7: the relatively obscure Riken Yamamoto. This brought the number of Japanese laureates to nine, two of whom shared the prize, making Japan tied with the U.S. as the countries with the most recipients.

Japan was once a nation of temples, shrines and castles, and as a result it developed excellent techniques in wooden construction and civil engineering. However, as the Edo Period (1603–1868) gave way to the Meiji Era (1868–1912), the construction of a modern nation became an urgent task, and the country looked to the West for guidance. In the field of architecture, the government invited the 25-year-old Briton Josiah Conder and he began teaching at the University of Tokyo’s College of Engineering (now the Faculty of Engineering) in 1877. In the ensuing 150 years, Japanese architects have earned a reputation as some of the best in the world.

The news that Yamamoto had won was greeted with some surprise in the architectural community, perhaps because many thought the prize only went to star architects who create flashy buildings. Yamamoto’s focus has always been on the creation of community through architecture — and it turned out that this very point was what impressed the jury.

“It was in mid-January that I was told by juror and prize Executive Director Manuela Luca-Dazio that I had won. I was surprised myself, but when I saw the nine members of the jury, I understood. The jury president, Anejandro Aravena, himself a laureate, has been closely involved in social movements, including a housing project for the poor in Chile. The jury also included diplomats and other nonarchitects. So I think they were strongly conscious of the social aspects of architecture, and that was what led to their decision,” Yamamoto explained.

Looking back at the previous laureates, it is clear that creators of highly artistic buildings did tend to win up until around the early 2000s. But from around the time of the Lehman shock in 2008 onward, more community-conscious architects started getting recognition. This was especially true with Aravena, who won in 2013, and also with the two Japanese who won in 2013 and 2014, Toyo Ito and Shigeru Ban.

“At the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, Ito asked himself what architects could do for the victims,” Yamamoto said. “His answer was the community spaces dubbed Minna no Ie (Homes for All) that were later built in several of the affected areas. Ban too has worked for war refugees and victims of natural disasters, starting with his paper church in the aftermath of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1996 and the shelters he provided for Rwandan refugees in 1999. I think the jury pays attention not only to the architecture itself but also to those social aspects.”

So, what does Yamamoto mean when he says he wants to create community through architecture? Let’s look at his Hiroshima Nishi Fire Station (2000) as an example. Fire stations are usually solidly constructed of concrete, giving them a closed and impregnable impression, but this one was characterized by its transparent glass walls that allowed people to see inside. Yamamoto says the effect of this transparency was to motivate the firefighters and also to reassure citizens that they are protected. “Firefighters don’t just go out when there is a disaster. The daily fire drills at the stations and practical training at the emergency centers are also part of community activities. By showing people these activities, we can raise awareness of disaster prevention in the community and foster stronger ties,” he said.

In discussing his Koyasu Elementary School in Yokohama (2018), which has more than 1,000 students, Yamamoto first pointed out that the sheer number of students made it difficult for a true community to form. He gave each classroom glass walls, so as not to make them closed off, and also created 4-meter-wide terraces overlooking the central playground, where students could grow plants and engage in other activities in the open. Yamamoto said: “We wanted architecture that would hint at some answers to the bigger question of what the future of education should look like. During athletic festivals, 2,000 parents gather on the terraces to watch the 1,000 kids compete. The terraces become a grandstand, and the entire school building, including the grounds, is like a giant outdoor theater. The students, teachers and parents all seemed really happy with it.”

Yamamoto has also launched an organization called Local Area Republic Labo to explore the nature of community in modern societies. He said a “local area republic” is a small self-governing body of 500 to 1,000 people — in simple terms, a neighborhood association. Until the end of the Edo Period, self-government in Japan was really conducted by small neighborhood associations. Over time, however, this sense of community has become less and less important, overtaken by the larger society that is the nation. Yamamoto is searching for ways to re-create lifestyles centered around small communities and exploring how architecture can foster that.

His way of thinking is catching on. He says he now receives requests for lectures and consultation from all over the world. Two days after our interview, he was heading off to Venezuela, and already this year he had been invited to Guatemala, Serbia, Indonesia, the Philippines and other countries with activist communities. It seems that high hopes are held globally for this acclaimed architect and his innovative ideas about communities.

PHOTO COURTESY OF MITSUMASA FUJITSUKA / VIA THE PRITZKER ARCHITECTURE PRIZE

RIKEN YAMAMOTO

Born in Beijing in 1945. He is an architect and the founder of the company Riken Yamamoto & Field Shop. He graduated from Nihon University’s Department of Architecture in 1968 and received a master of arts degree in architecture from Tokyo University of the Arts in 1971. He was a research student at the Hara Laboratory at the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Industrial Science.

He was appointed as a visiting professor at Kanagawa University in 2024. He holds the titles of professor emeritus and honorary doctor from Yokohama National University and honorary professor and honorary doctor of engineering from Nihon University. He was a visiting professor at Tokyo University of the Arts from 2022 to 2024 and previously taught at Yokohama National University’s Graduate School of Architecture from 2007 to 2011 and served as the president of Nagoya Zokei University of Art and Design from 2018 to 2022.

Some of his notable works include Nagoya Zokei’s new campus, The Circle at Zurich Airport, the Yokosuka Museum of Art, the campuses of Future University Hakodate and Saitama Prefectural University, and his own house, Gazebo. He has also undertaken projects for mixed-use facilities, public buildings and residential complexes in China, South Korea and Taiwan.

PHOTO: YOSHIAKI TSUTSUI

山本理顕が考える「建築を通じたコミュニティの創出」とは。

建築界のノーベル賞と呼ばれる賞がある。それが「プリツカー建築賞」だ。賞の創設は1979年。今年2024年は建築家の山本理顕がその栄光に輝いた。これで日本人建築家の受賞は8組9名となり、アメリカと並び、世界最多受賞国となった。山本理顕のプリツカー建築賞受賞は建築界を驚かせた。派手な建築を作るスター建築家が受賞するものという先入観が一般にあったからかもしれない。

しかし山本が一貫して訴え、作品を通じ追及してきたのは「建築を通じたコミュニティの創出」。プリツカー賞の審査員から高く評価されたのもその点にあった。

「受賞の知らせに私自身も驚きましたが、審査委員長でこの賞の受賞者でもあるチリ人建築家アレハンドロ・アラヴェナさんは、チリで貧困に苦しむ人たちのための住宅プロジェクトを行うなど社会的な活動に取り組む建築家です。また審査員には外交官など建築家以外の人もいます。そのため“建築の社会性“に対し強い意識をもっていると思います。そういったことが私の受賞につながったのではないかと思いました」。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 42 article list page