July 25, 2025

Ise Jingu ritual’s photographer discusses the shrine

INTERVIEW

© MASAAKI MIYAZAWA

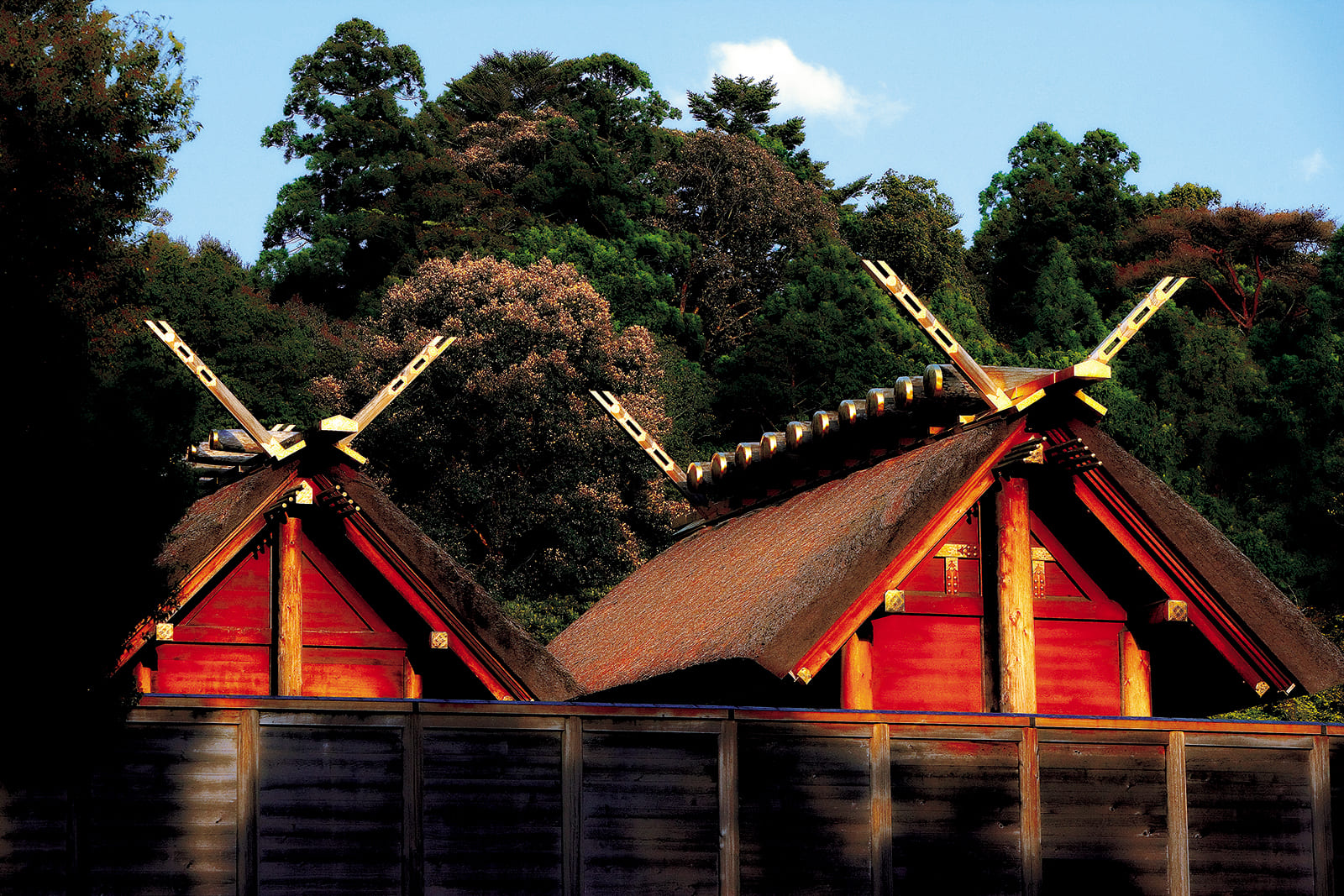

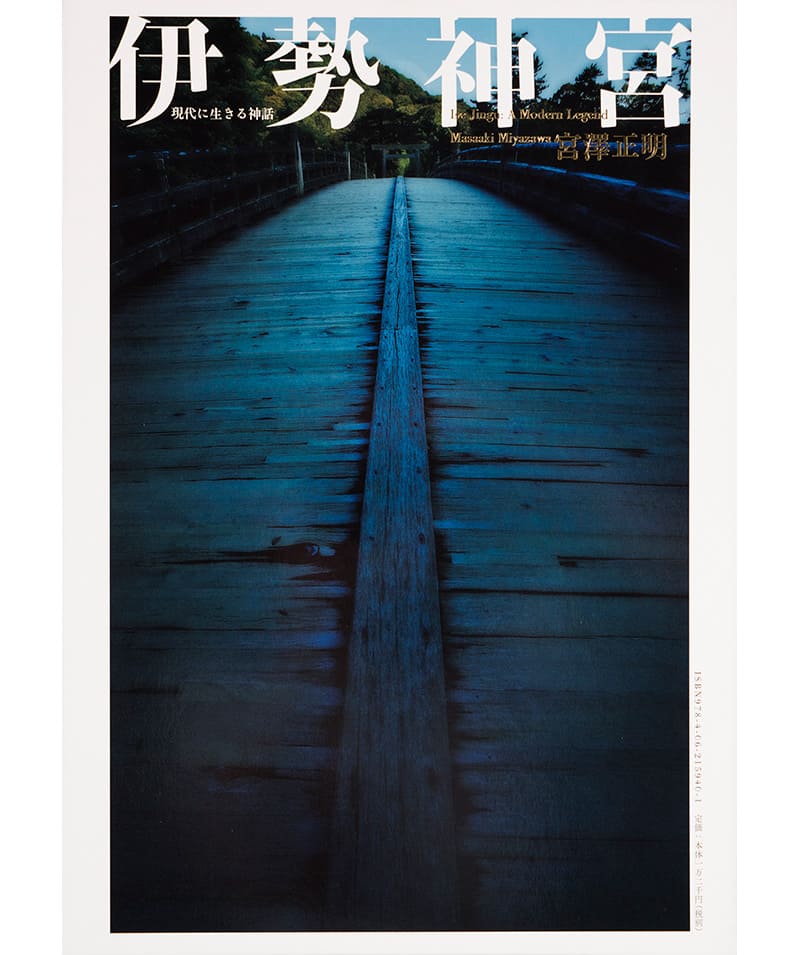

The oldest wooden structure in Japan is Horyuji temple in Nara Prefecture, believed to have been built in 607. However, its architectural style was strongly influenced by China and the Korean Peninsula. If you are looking for the oldest example of a uniquely Japanese style of architecture, then look no further than Ise Jingu (officially known as “Jingu”) in the Mie Prefecture city of Ise.

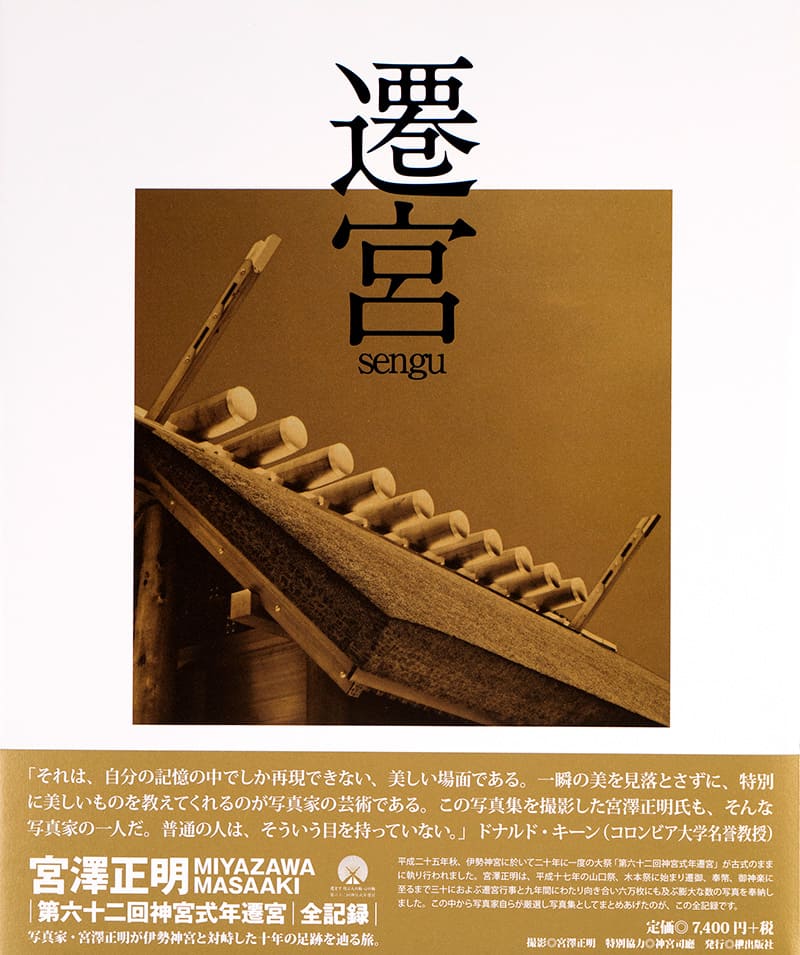

The shrine is dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu, from whom the imperial family is said to descend, and is the highest-ranking Shinto shrine in Japan. Its buildings are rebuilt every 20 years in accordance with the Shikinen Sengu ceremony, but their architectural style remains unchanged from at least 1,300 years ago, when the ceremony was first held. In terms of architectural heritage, there is little else like it in the world.

The shrine’s 63rd Shikinen Sengu will take place in 2033, and the first preparatory ritual for that process, the Yamaguchi Festival, was held on May 2. This is a ritual to pray for the safety of the tree-felling that is necessary for the shrine’s rebuilding. Further rituals related to the reconstruction will be held, leading up to the eventual relocation of the deities into their new home. All of these will be conducted over the next nine years until Shikinen Sengu is completed.

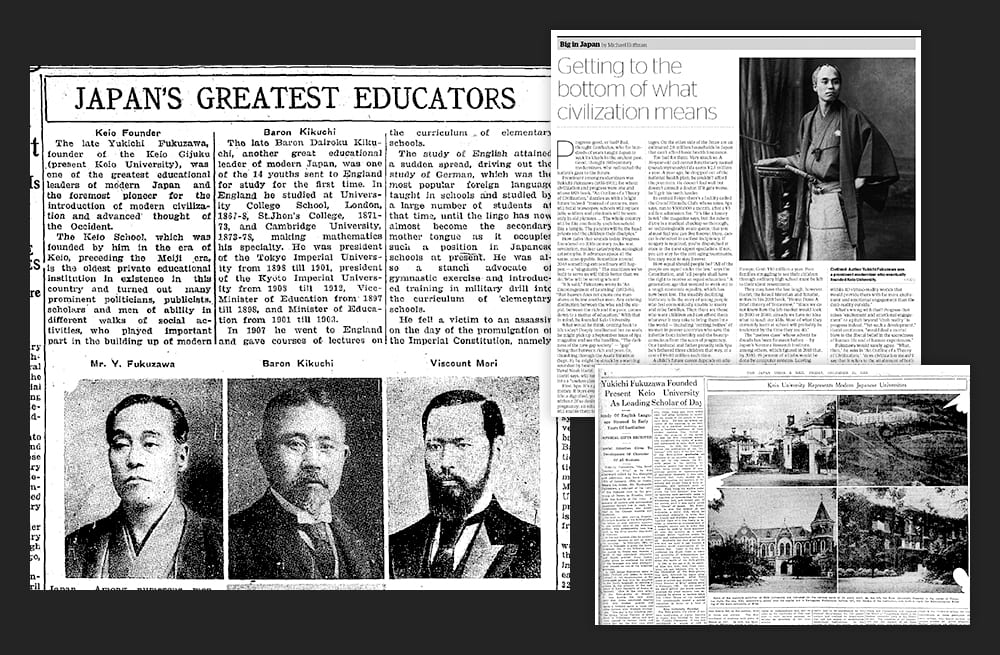

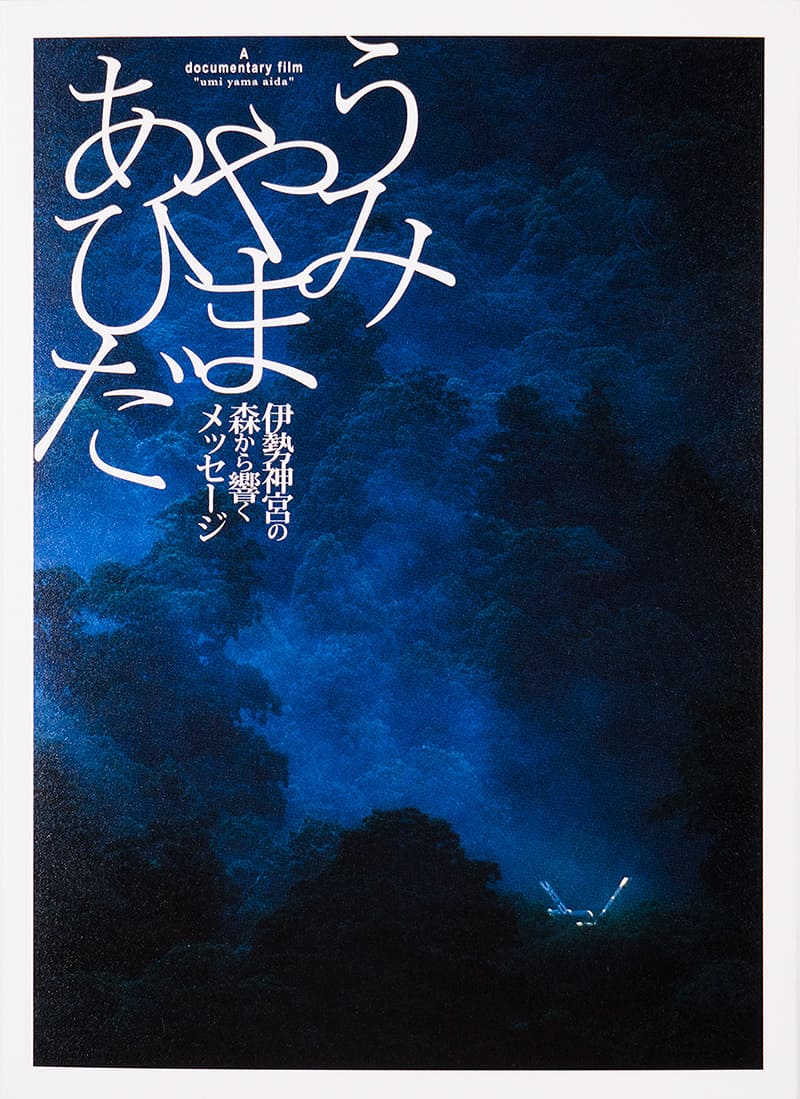

Masaaki Miyazawa served as official photographer and filmmaker for almost all of the rituals of the 62nd Shikinen Sengu, which was completed in 2013. The result was his first documentary film, “Umi Yama Aida” (“In Between Mountains and Oceans”), which received high praise and won the Best Foreign Language Documentary Award at the 2015 Madrid International Film Festival. Miyazawa chose not to film the ancient rituals straight, but instead made technical adjustments to enhance their vividness and color so they would “remain as mythology” in his viewers’ memories. Surprisingly, mythology still surrounds the Ise Jingu rituals — proof that Ise Jingu’s architecture and its spirit of sustainability have been preserved.

At the beginning of “Umi Yama Aida,” Shinnyo Kawai, a priest at Ise Jingu at the time, said of Shikinen Sengu, “By rebuilding the shrine anew every 20 years, we are able to keep ancient forms and spirits alive today and into the future.”

Indeed, if something is repeated every 20 years, one could conceivably witness it as a child, get involved as a young adult and later pass on that knowledge to the next generation in old age.

The 20-year interval makes it easier to pass on the various techniques necessary to reproduce this ancient architectural style, known as “shinmei-zukuri,” including the cypress wood construction, hottate-bashira pillars and thatched roof, not to mention the many rituals required for performing the various ceremonies.

Ise Jingu consists of not one but 125 shrines, and all of them are renewed together, as are all of the gods’ clothes, ornaments and furnishings, and all of the weapons, harnesses, instruments, stationery and everyday items used in ceremonies, such as swords, bows and arrows, and textile tools. The production of these items is undertaken by Japan’s leading craftsmen and artisans in the fields of lacquerware, woodwork, metalwork, and dyeing and weaving. This is in keeping with the Japanese spirit of tokowaka, which means to wish for eternal youth and the light of life that transcends the passage of time. In this way, Shikinen Sengu in fact serves as a system for preserving traditional crafts, including architecture.

Miyazawa said Shikinen Sengu also embodies Japan’s ecological spirit.

“After photographing the final ceremony of moving the deities into the new shrine, I suddenly remembered the tree-felling ceremony that had taken place at the very beginning. 350-year-old hinoki cypress trees grown in the Kiso Mountains that straddle Nagano and Gifu prefectures are felled using traditional techniques, and as they fall they make a sharp squeaking sound. This is the moment when the hinoki tree ends its 350-year life as a tree and begins its new life as timber for the shrine. Meanwhile, the old shrine pavilions that have completed their role at Ise Jingu are dismantled and reused as torii gates within Ise Jingu or as materials for renovating torii gates and shrine pavilions elsewhere in Japan, including in areas damaged by natural disasters. In other words, the timber continues to change form, is reincarnated and serves to connect Ise with all regions of the nation. I believe this is a manifestation of the quite unique Japanese view of nature.”

The Ise Jingu grounds are vast, at 5,500 hectares, roughly one-quarter of the size of Ise city and similar in scale to downtown Paris. Most of this land is covered with forest.

“Ise Jingu enshrines the deity Amaterasu, but I think the essence of Ise Jingu actually lies in the forest,” Miyazawa said. “There are mountains and there is the sea, and I think the shrine expresses a sense of awe for the forest that connects the two.

“A meal known as go-shinsen has apparently been offered to the gods at Ise Jingu every morning and evening for 1,500 years, and the shrine is actually self-sufficient in rice, vegetables, fruits, salt and other ingredients. These days, Japan’s food self-sufficiency rate has dropped to 30%, but until the end of the Edo Period (1603-1868), self-sufficiency was the norm, and people must have lived in this way since ancient times. Naturally, all foodstuffs come from the mountains, the sea and the forests. The rain that falls on the mountains enriches the fields, and the nutrients from the mountains are delivered to the sea, where fish and seafood grow in a cycle. Ise Jingu is an expression of gratitude for this cycle that is repeated by nature.

“Every local town in Japan has its own shrine, each with a protective forest that connects it to Ise Jingu. So, even by paying homage at a local shrine, you are connecting to Ise and expressing thanks for the blessings of nature. I hope we can share this message with the world.”

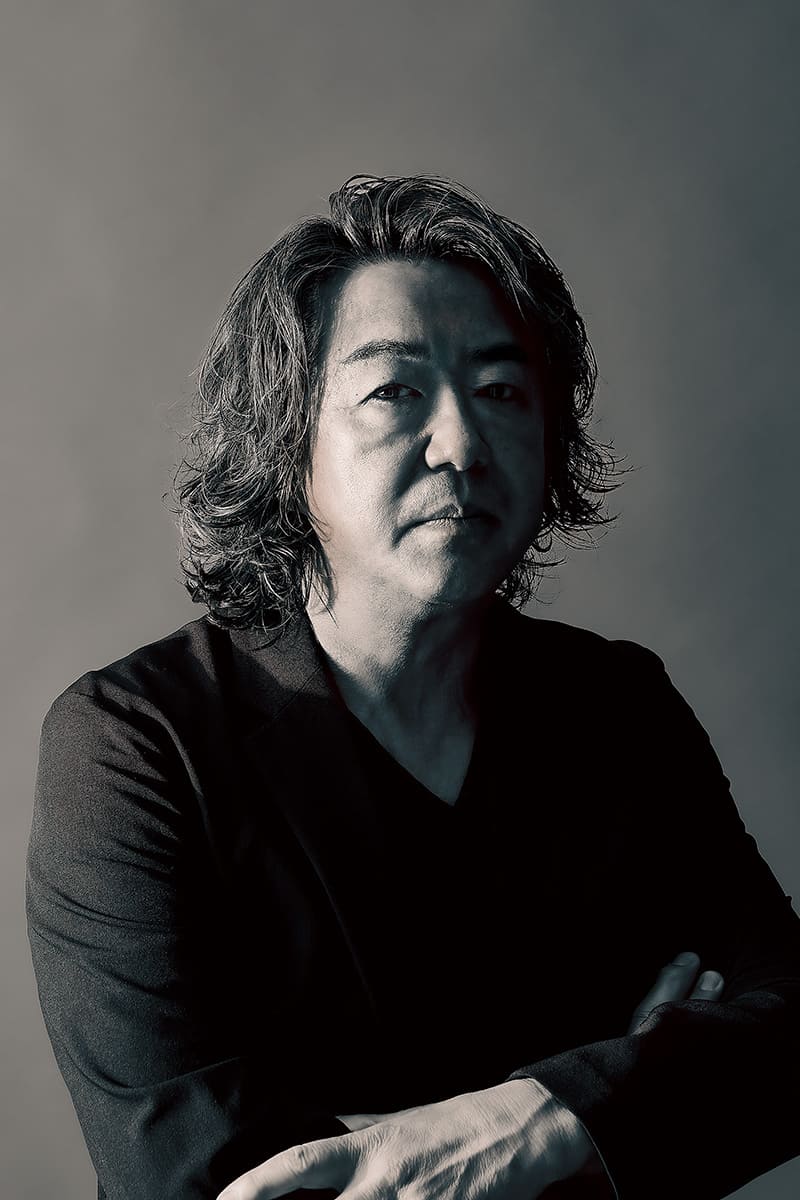

MASAAKI MIYAZAWA

Miyazawa is a photographer and film director born in 1960 in Tokyo. He won the New York International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award for Young Photographer in 1985 with “Ten Nights of Dreams,” a work made using infrared film. He has served as a specially appointed lecturer at Nihon University College of Art’s Department of Photography since 2017 and has delivered special lectures at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. He also works extensively in the fields of advertising, magazines and fashion. His second film documents the work of Shoko Kanazawa, a talented calligrapher with Down syndrome. He has published more than 150 books of his photographs.

https://masaakimiyazawa.jp/

「式年遷宮」を撮影した写真家が語る伊勢神宮。

日本最古の木造建築は奈良県にある法隆寺だが、日本最古の建築様式を今に伝えているのは三重県の伊勢神宮だ。「式年遷宮」で建て替えを繰り返しながら、1300年前の日本独自の形態を今に引き継ぐ。

宮澤正明は2013年に行われた伊勢神宮第62回式年遷宮のほぼすべての神事を、公式記録としてカメラに収めた写真家だ。式年遷宮は日本のエコロジカルな精神を体現すると宮澤は語る。

伐採された木は社殿の用材となり、式年遷宮で解体された後も日本各地の神社の社殿の改修資材として再利用され、命を繋いでいく。「同時に、伊勢と日本全国の地方も木の部材を通じ繋がっていくんです」と宮澤は言う。

ちなみに伊勢神宮の宮域は5,500ヘクタールと広大で、伊勢市のおおよそ1/4を占める。「伊勢神宮の本質は“森”にある」と宮澤は指摘する。例えば、我々の食材はすべて森を挟んで、山と海がある自然の循環の賜物といえる。その恵みの感謝の表れが伊勢神宮であり、鎮守の森を通じて全国津々浦々の小さな神社にも繋がっているのだ。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 50 article list page