April 25, 2025

Muji has been sustainable from the beginning

VOL. 16: Ryohin Keikaku Co. Ltd.

Muji’s strong points

1.Has put importance on sustainability in all product development since its founding in 1980

2.Sales of reused clothing have grown to 55,000 garments annually

3.Has expanded recycling to include PET bottles, plastic space organizers and comforters

4.Has begun collaborating with other companies on renewable energy generation and horizontal textile recycling

The Mujirushi Ryohin brand offers a wide range of products from clothing, household goods, furniture and food to even homes, all wrapped in a unique worldview. The brand adopted the name Muji in 1991, when its first overseas store opened in London.

Since then, it has gained recognition overseas and grown to 1,364 outlets in 29 countries and regions. Consolidated sales for its operating company, Ryohin Keikaku Co. Ltd. reached a record high of ¥661.6 billion ($4.4 billion) for the fiscal year that ended last August.

Ryohin Keikaku is undoubtedly one of Japan’s leading companies in sustainability. However, it differs slightly from the companies covered in this column in the past.

It does not particularly stand out in terms of external evaluations, including by the international nonprofit organization CDP — its 2023 score for climate change was A-, and it got a B for water security.

Nor is it especially bold in setting targets for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions — it currently targets only a 50% reduction in Scope 1 and 2 direct and indirect emissions by 2030 from the 2021 levels, and there is no mention of net zero.

Furthermore, one does not find an SDG logo on its website, something other companies’ sites often feature.

Yet it is one of the brands that consumers most often associate with the U.N.’s sustainable development goals. The reasons for this are packed into its history, philosophy and products.

History of eliminating waste

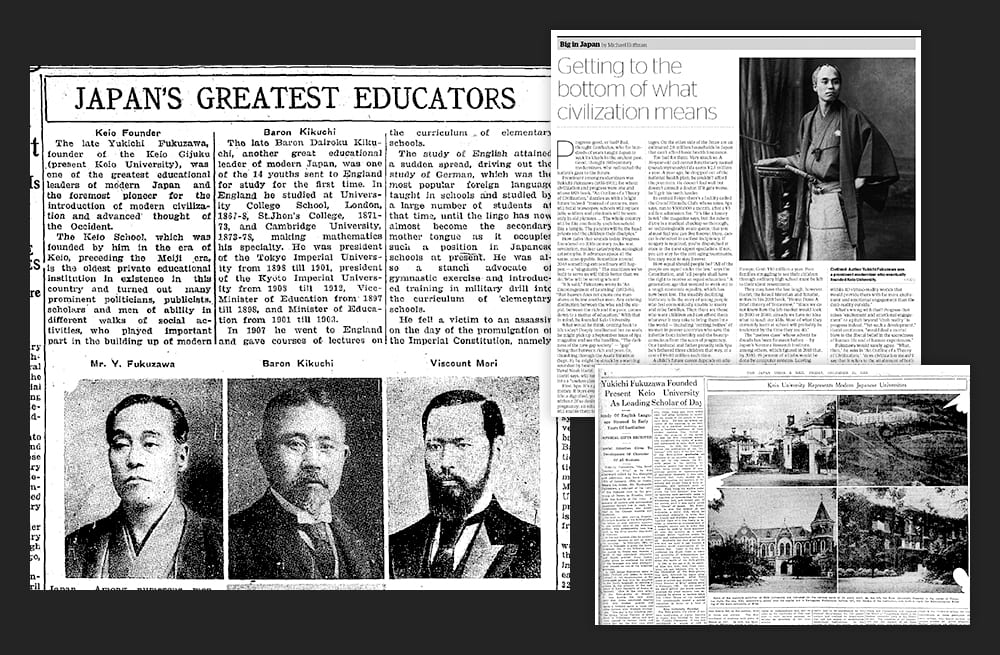

Mujirushi Ryohin was launched in 1980 as a lifestyle brand based on the concept of “cheap for a reason.” The name means “unbranded quality products.”

“It began as an antithesis to the trend represented by the term ‘economic bubble’ at the time, in which flashy goods and things were popular, and we thought, ‘What if we offered goods that are simple but of good quality?’” said Kenta Hochido, Ryohin Keikaku’s executive officer in charge of sustainability (see the article in the box).

“From the very beginning, we have continued to make products that are practical while paying attention to our ‘three principles’ — namely, selection of materials, streamlining of processes and simplification of packaging — for all of our products,” he added.

Its products have included Imperfect Dried Shiitake and Irregular Baumkuchen, launched respectively in 1980 and 2000, which include misshapen items. There are Memo Book, launched in 1981, whose paper is unbleached and 70% recycled, and a series of boil-in-the-bag foods launched in the 1990s that come without the external boxes typically used by other Japanese companies. Ochiwata Fukin, launched in 2007, is a dish cloth made from cotton waste generated at spinning mills.

Since the 1980s, the company has always selected materials with an emphasis on quality, worked to streamline production processes, simplified packaging and decoration, and offered products at low prices.

Muji efficiently makes simple, good and low-priced products. Its philosophy and practices directly relate to the SDGs and the practice of ESG (environmental, social and governance) management. Muji’s stance struck a chord with consumers even in the days when the terms “SDGs” and “ESG” did not yet exist.

Muji’s style can also be seen in the apparel segment, which currently accounts for nearly 40% of Ryohin Keikaku’s consolidated net income.

The Washed Shirt, launched in 1983, is a 100% cotton product. Muji washed but did away with also starching and ironing the shirts, steps typically taken to improve the appearance of clothing on store shelves.

Since the company could not artificially make the shirts seem better than they actually are, it selected high-quality materials and cut costs by streamlining the production process. The shirts, which gained a favorable reputation for a comfortable feel that doesn’t change after further washing, have become a long seller.

To attach tags to products, the company opts to use paper strings rather than plastic. They are more difficult to fasten and more likely to come off, making them more inconvenient for staff, but even so, the company is sticking with them.

© OSAMU INOUE

Reuse and recycling

After working on streamlining operations, Ryohin Keikaku began to work on reuse and recycling in earnest around 2010.

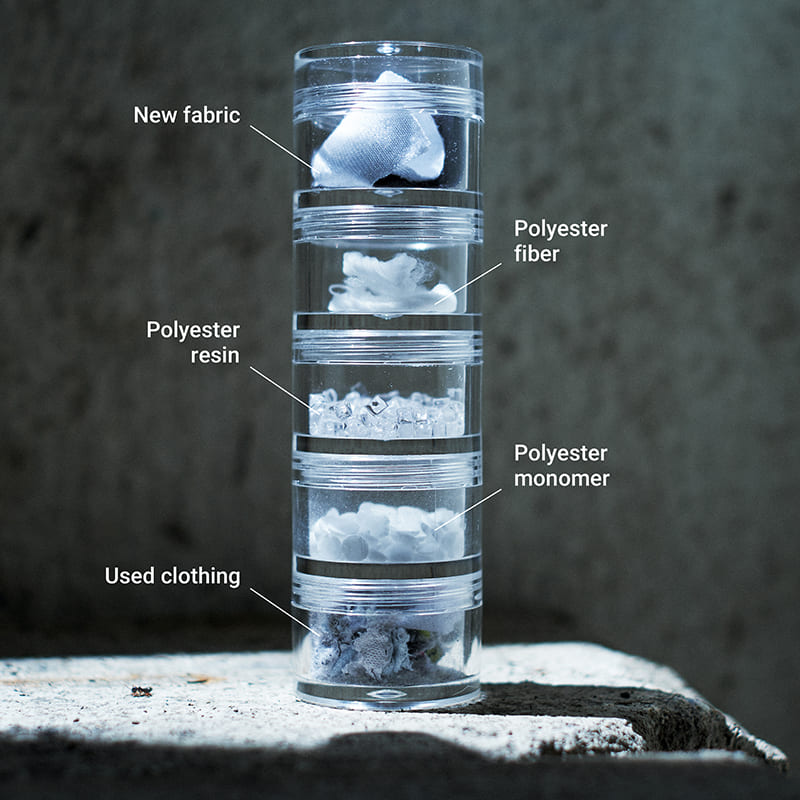

It began by joining a project to collect clothes and recycle them into bioethanol. But after beginning to collect its old clothes, the company realized many were still in good enough condition to be worn. Thus, in 2015, it decided to enter the reuse business, in which collected old clothing — excluding underwear, socks, shoes and bags — is cleaned, remade and resold.

The company launched “redyed clothes,” one-of-a-kind products made from collected clothes that are redyed indigo, black or other colors to add new value. It then expanded the lineup to include, for example, “connected clothes,” which are made by combining parts of different pieces of clothing.

By the end of August 2024, the company had increased the annual amount of clothing it collected to about 97 tons and the annual sales of resulting garments to 55,746 items.

“We have many customers passionate about the products, and many local governments appreciate them, because we take responsibility in giving a new life to our collected items,” said Rie Anan, Ryohin Keikaku’s director of corporate planning.

Still, the company has faced challenges. Used clothes are collected at almost all of its more than 600 stores in Japan but sold only at 31 large stores.

“The amount of clothes collected is still too small to be able to offer the products at all our stores. In other words, supply is not keeping up with demand,” Anan said.

But instead of stopping, Muji is moving forward with reuse and recycling.

It expanded the scope of items collected at its stores to include skin-care PET bottles in 2020 and plastic space organizers in 2023 — both of which are recycled into polypropylene for new products — and down comforters in 2024.

The company is now working on a project to recycle those bottles back into bottles for the same products, a process known as horizontal recycling.

“It is a project involving cosmetics, and so it took very long to find a partner company, but now we are finally seeing some progress,” Anan said.

ReMuji

Ryohin Keikaku named these initiatives ReMuji and set up a circular business division to take charge of them. At the same time, it introduced a new idea to accelerate collection at stores: a system in which an incentive of 1,000 Muji miles is awarded to customers who present the Muji app when they bring in items for recycling.

Some of its outlets have begun collecting used Muji paper clothes hangers, microbead sofas and metal shelves as well, although no incentive points are awarded. These stores also collect unwanted items such as books and food, including items that Muji does not sell, and some donate them to day care facilities and food banks through local municipalities.

The volume of items collected, reused and recycled, including plastics, still remains small and has no impact on Ryohin Keikaku’s business performance. The process of collecting and recycling is costly and time-consuming. It adds burdens on store operations and takes up additional space to store collected materials.

Yet Ryohin Keikaku is expanding the scope of collection and even spending money on campaigns — proof that it is serious about reuse and recycling.

“We were prioritizing using as little resources as possible, and this naturally led us toward reuse and recycling,” Hochido said, explaining why the company is working on ReMuji. “We began in the spirit of, ‘Let’s just do it as long as it’s something nice to have.’ That’s the culture of Ryohin Keikaku.”

Anan added: “We are a company that can put ideas into action. Another factor was that our ‘second founding’ heightened the sense that we needed to do more for resource circulation.”

The “second founding” of the company was declared by Nobuo Domae, currently Ryohin Keikaku’s chairperson, after he was appointed president in September 2021. He set a 2030 target of realizing a “community-based business model centering on independent management of stores” and redefined the corporate purpose as “to contribute to the creation of ‘truthful and sustainable life for all’ through our products, services, stores and business activities; believing ‘human society rich in heart, with balanced relationship between human, nature and artifacts.’”

Until then, the company had been committed to manufacturing good products in line with its “three reasons,” but now it added the focal points of “community” and “society” and began to expand into provincial cities. Sales increased 46% over the three years after Domae became president.

Domae arguably shifted the company’s focus from products toward society. In a way, he made the stores play the role of community centers, partly by making them collect items for recycling.

© RYOHIN KEIKAKU CO. LTD.

Collaborations

Ryohin Keikaku is a remarkable company in that all of its products have been sustainable from the very beginning. The style of manufacturing that the company has pursued naturally led it to sustainability and ESG — it did not take on this challenge just to follow trends or because it felt pressured.

The company has always focused primarily on the honest pursuit of the Muji way, and that is why it does not prominently display the SDG logo as a show of sustainability-mindedness and why it does not pledge to make itself carbon-neutral, though it is making efforts to improve external evaluations.

Now that society has been added as a focus, Ryohin Keikaku’s sustainability strategy is gradually changing.

One of the reasons why it does not set greenhouse gas reduction targets, including Scope 3 supply chain emissions, has been that measuring and controlling emissions was difficult.

Until now, the company has been reluctant to publicly disclose reduction targets because of its sense of responsibility.

“We cannot make a pledge unless we have a clear road map and rationale for reductions,” Anan said. But “our ESG division is persuading our colleagues that we should set a target in Scope 3.”

There are also initiatives underway that are not centered on manufacturing. This past January, Ryohin Keikaku announced that it had signed a deal with Jera Co., a major Japanese power company, and the two were set to begin a feasibility study on generating power using renewable sources such as solar installations on farmland, including abandoned farmland. The company has set a goal of getting 100% of its electricity from renewable sources, which it expects to achieve domestically through the projected power business.

Ryohin Keikaku also has begun to collaborate with another company on recycling. Last December, it announced a plan to work with Teijin Frontier Co., a subsidiary of the major chemical maker Teijin Ltd., on a project to recycle polyester and other materials from collected clothing for horizontal fiber-to-fiber recycling. It also plans to launch a consortium with other companies and local governments to conduct demonstration experiments.

“If you tried to do horizontal recycling, it wouldn’t be easy with just one company, or two. The key for us is to make this consortium as large as possible,” Anan said. “And we think that is what is necessary for society at large.”

For the CDP’s 2024 rankings, released this February, Ryohin Keikaku for the first time responded to the survey in the category of forests, in addition to its usual responses on climate change and water security.

“We have finally entered a phase where we can turn our attention to external evaluations and hope that we can begin to make some progress while still continuing to prioritize the uniqueness that makes Muji what it is,” Hochido said.

The surveys resulted in scores of B- for forests, B for climate change and A- for water security.

Ryohin Keikaku has only just begun to collaborate with other companies and communities on sustainability. When its new initiatives and product collection campaigns bear fruit, objective evaluations will go up from here.

“Our goal is to become a leader in ESG by 2030,” Anan said. Given the potential of Ryohin Keikaku, which is arguably a pioneer of sustainability brands, it has a good chance of gaining recognition as the leader in both name and reality.

© RYOHIN KEIKAKU CO. LTD.

‘Three reasons’ that have remained unchanged since 1980

Kenta Hochido

Executive officer and head of corporate planning

We are very serious in working on our sustainability initiatives. But I must add that we are serious in our unique Muji way.

We do care about scores given by external evaluation agencies. But it is not our style to focus on activities that are only intended to raise such scores. From a management perspective, our first priority is that any initiative must be in line with the Muji way.

In the first place, Ryohin Keikaku is a manufacturer and retailer. That means we must be responsible toward our customers, society and the global environment. We are proud to have been fulfilling this responsibility in our own way since 1980, when we started out as the Mujirushi Ryohin brand.

Honestly, we would be happy if we received high evaluations from external entities as we continued activities in the Muji way. But we do not go out of our way to try to improve externally set indicators.

There are many products and terms that embody Muji-ness, but what makes us Muji boils down to the “three principles in manufacturing” that we have valued since 1980: selection of materials, streamlining of processes and simplification of packaging.

Take the selection of materials, for example. It means taking advantage of things that would otherwise be thrown away just because of poor appearance even though their quality is fine, or seasonal items that can be procured in large quantities at low cost, in order to offer quality products at low prices. These include foods that are both delicious and healthy, clothes that are comfortable and fit the body, and household goods designed with priority on convenience of use.

We have been saying and doing things like this for the past 45 years. We have a promotional poster from 1981 featuring the catchphrase “The entire body of a salmon is salmon.” It was intended to express the idea that a food item is valuable as a whole, with no part going to waste, and that it is good as long as it is delicious. Posters like that still hang all over our offices, and this kind of thinking has permeated our consciousness.

In 2021, we redefined our corporate philosophy and positioned it as our “second founding.” But we did not change our thinking in any way from an ESG perspective. There was a policy shift on the business side from opening stores mainly in urban areas to expanding into provincial areas, and this change necessitated expressing the original idea in new language.

What we want to do is work in a normal way to create a lifestyle and society that feel good and help make the future 100 years from now a better one. What I mean by “feels good” is fitting or being just right for each individual. In the case of clothing, some people feel that way when they use reused products. In the case of food, some people feel that it is good food as long as it tastes good, no matter what shape it is.

We want to continue to develop products that are unique to Muji, always prioritizing being unique, for such people.

もともとサステナブルな「無印良品(MUJI)」。

衣料や生活雑貨、家具、食品、さらには家まで、幅広い商品を独自の世界観で展開する「無印良品(MUJI)」。消費者からはSDGsに最も近いブランドの一つとして認知されている。その理由は、同社の来歴や理念、商品に詰まっている。

誕生した1980年代から今に至るまで、すべての商品において、質重視で素材を選別し、工程の無駄を廃し、包装や装飾を簡素にした上で、低価格で提供。その理念やコンセプトはSDGsへの貢献やESG経営の実践に直結する。まだ世の中にSDGsやESGといった言葉がない時代から、MUJIの姿勢は消費者の琴線に触れた。

まずは、合理化で「リデュース」に取り組んだ良品計画は、2010年頃から「リユース・リサイクル」にも本格的に乗り出した。

そして2021年9月、現会長の堂前宜夫氏が社長に就任すると、「第二創業」を宣言。企業理念を再定義し、“モノ軸”中心から“社会軸”へと歩み寄った今、良品計画のサステナビリティ戦略は少しずつ変化しつつある。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 47 article list page