February 09, 2026

Yamagata art university tackles challenges of community decline

In 2025, the city of Yamagata was selected as the first Destination Region — a Japanese municipality that The Japan Times wishes to tell the world about. It is home to a university providing practical education in the fields of art and design through social experiments and projects involving local communities.

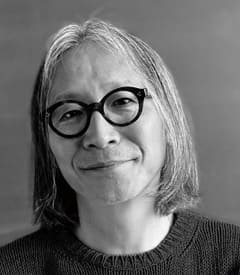

In a recent interview with The Japan Times, Daisuke Nakayama, a contemporary artist and president of the Tohoku University of Art and Design (TUAD), spoke about what it means to study art and design in Yamagata and the connection between the students and the city.

Nakayama was born and grew up in Kagawa Prefecture. Prior to joining TUAD, he was based in New York while engaging in art projects and exhibitions across the world. Although he got offers from various other universities in Japan, he chose TUAD, attracted by its uniqueness compared to art colleges in urban areas. “Ever since, I have been commuting to Yamagata for 18 years. There are things I notice about the city because I can see it from an objective point of view — the benefit of not living there,” he said.

Nakayama thinks that Yamagata is ahead of other cities in Japan — or even elsewhere in the world — in terms of experiencing social issues stemming from the decline of rural areas in a mature economy. He pointed out that although the global population is growing, some countries are experiencing a decline in population. Historically, he said, societies tend to follow a cycle of growth followed by decline. “This means that the populations of India and many countries in South America and Africa are likely to eventually decrease too,” he said.

Nakayama emphasized that the university uses the entire city as its field, providing its students with hands-on learning opportunities through tackling the challenges faced by the declining community. “Here we can truly nurture people, whereas art universities in big cities often merely serve as gateways to relevant industries,” he said.

Among the diverse experimental projects students undertake in the city, renovating vacant houses is particularly common. “Yamagata wasn’t bombed during World War II, so relatively many old buildings remain. This initiative focuses on renovating them rather than demolishing them, exploring new ways to use them,” Nakayama said.

There are also many examples of the university and its students participating in the creation of various facilities in and around the city where local people can gather and visitors can drop by. One example was a project in Oe, a town northwest of Yamagata, where students and faculty members from the Community Design Course in the Design Engineering Department participated in the creation of Atera, a community center housed in a quaint old former bank building.

“Several years ago, we conducted a social experiment installing dedicated bicycle lanes along the city’s main street,” Nakayama said. Students also organized events such as street markets. Nakayama pointed out that creating something intended for everyone is challenging. To help students overcome that, he and the other faculty members keep one thing in mind: “We make sure the students understand that they are working on a public project.”

The campus itself has an open atmosphere. It has no wall-like enclosure, being designed to blend seamlessly into the city. There are galleries on campus that are open to the public, providing citizens and outside visitors with opportunities to enjoy students’ works.

Nakayama believes that one of the university’s next missions will be to demonstrate how to gracefully end a community. “For example, let’s say there’s an old bridge, and beyond the bridge is a community of only 50 people, and it is expected to shrink even further. Should we spend a billion yen ($6 million) to build a new bridge when the old one is broken? Wouldn’t it make more sense to relocate the entire community? We need to think about these things realistically,” he said.

He believes that failing to have concrete discussions about how to end a community would only result in its gradual decline, with abandoned houses left to decay. “There are things we can do. For example, we can create a facility where former residents can gather in their hometown and continue holding their traditional festivals while returning the rest of the village to nature. I believe it is possible to create landscapes that embody a universal beauty — a beauty that allows visitors to imagine how people lived several decades ago,” he said, hoping that such efforts will help rural communities not only in Japan, but around the world, plan for the future.

This series will continue with monthly profiles of people working in Yamagata city.