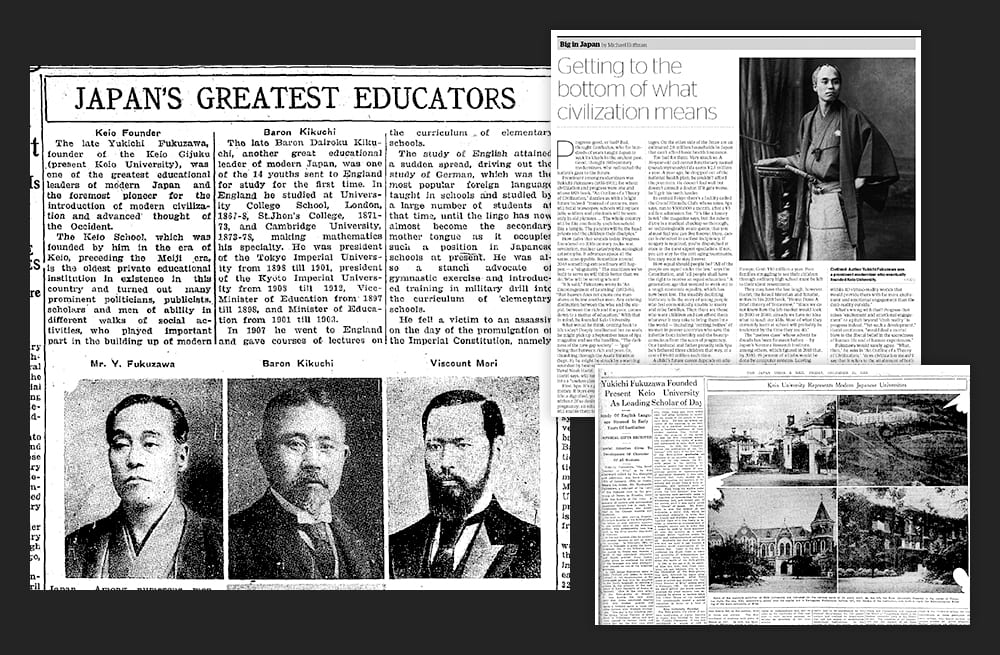

October 24, 2025

Traditional dishes that came from tea ceremony

INTERVIEW

Japanese tableware differs from that of any other country. For example, although Western meals generally are served on matching round porcelain dishes, Japanese cuisine is traditionally presented on varying plates and bowls. One prominent example was the court banquets held in October 2019 to celebrate the emperor’s enthronement, at which guests from Japan and around the world were served Japanese cuisine on a range of tableware. The lacquerware alone included round bowls, square ones and fan-shaped pieces; porcelain dishes included blue-and-white designs and gold-painted phoenixes — even bamboo baskets were used.

In solemn Shinto or Buddhist ceremonies, vessels of the same material do tend to be used, but in general Japanese cuisine, a single course may feature a range of different crafts: porcelain, soft-textured pottery (glazed or unglazed) and even lacquerware or wooden items. The prevalence of soft-textured vessels likely relates to the fact that in Japan, meals are eaten with wooden chopsticks rather than metal cutlery. Furthermore, diners hold their bowls in their hands and sip soup directly from the bowl. This likely explains the avoidance of heat-conductive materials like porcelain and metal. Beyond the range of patterns and colors, the variety in shapes is also endless — from circles and squares to shapes mimicking living creatures like flowers and birds, or landscapes such as mountains, houses and waves.

This is because formal Japanese cuisine is based on the style of chakaiseki, a meal served before the tea ceremony. While there are various schools of tea ceremony, the wabi-cha perfected by Sen no Rikyu in the 16th century is now considered mainstream in Japan. Before Rikyu’s time, matching sets of highly prized utensils from China known as Tang ware were used when serving tea to shoguns, nobles or deities. Rikyu, however, preferred combining simple vessels made in different locations around Japan, be they ceramic, bamboo or wood. Chinese vessels were also used, but not the noble pieces fired in imperial kilns for the emperor. Instead, everyday Chinese vessels fired in unofficial kilns that aligned with the tea master’s aesthetic sensibility were used.

Furthermore, while many Japanese ceramics were certainly influenced by the techniques and forms of Tang ware, others differed from their symmetrical and decorative Chinese counterparts because the Japanese often cherished imperfections. Since ancient times, it had been common to create pieces imitating the form or patterns of existing masterpieces. In the world of the tea ceremony, such imitations are not considered forgeries but are referred to as reproductions and are held in high regard by craftspeople, sellers, buyers and users. If a reproduction was made by a master craftsman, its value is considerable. Consequently, museums house a vast number of such reproductions.

This tendency has been passed down to modern tea practitioners and even carried forward into Japanese restaurants. Indeed, visiting traditional Japanese restaurants or kaiseki establishments allows one to encounter traditional craft vessels steeped in this historical lineage. Much like favoring locally sourced ingredients, most restaurants also prefer locally produced tableware. In Tokyo, where ingredients are sourced from across the nation, it is natural that many restaurants also feature tableware from all over Japan.

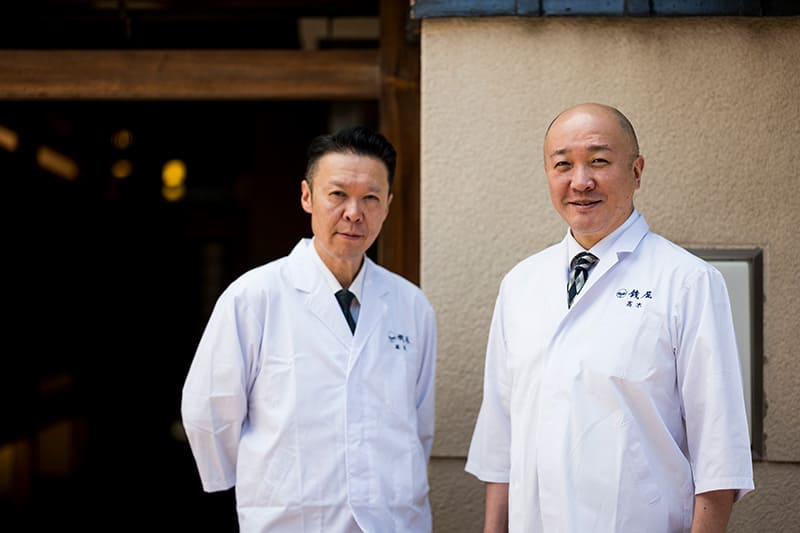

So what about the “home of crafts” that is Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture, the one-time Kaga domain heartland that promoted crafts heavily during the Edo Period (1603-1868)? At the city’s Japanese restaurant Zeniya, we spoke with owner Shinichiro Takagi and his brother Jiro, the head chef, while reviewing the plates and bowls they use to serve their food.

PHOTOS:NAOFUMI MIYAJIMA

ZENIYA

Established in 1970, Zeniya is one of the leading traditional Japanese restaurants in Kanazawa. It has a seven-seat counter and five tatami rooms (all with tables or sunken kotatsu tables). From early November through March, winter delicacies like crab and yellowtail feature prominently. The omakase kaiseki course, starting at ¥27,720 ($185), including private room fee, tax and service charge, is available for both lunch and dinner. Zeniya Singapore opened in Singapore in 2023.

Address: 2-29-7 Katamachi, Kanazawa-shi, Ishikawa Prefecture

Tel: 076-233-3331

Website: https://zeniya.co.jp

“While we obviously use local crafts like Kutani ware, Wajima lacquerware and Kaga maki-e (gold or silver on lacquer), we also use tableware made in Kyoto,” Jiro Takagi said. “We select pieces for a roughly 10-course meal — from the first appetizer to sweets and tea — blending contemporary pieces, antiques and varying colors to complement each dish. We always include a few items that visually signal the season: chrysanthemums and autumn leaves in fall, cherry blossoms in spring.”

Certainly, many Japanese bowls and plates feature designs that evoke the four seasons. Particularly notable are the works of Ogata Kenzan, a master craftsman of the Edo Period who has many pieces that have been designated as important cultural properties. His bowls often express the seasons through their bold designs, and many reproductions have been made. There is a reason that, despite the variety of vessels used, overall harmony can still be maintained.

“Unlike the opulent interiors of European mansions, in Japan, spaces as simple as they are austere — like tearooms — become the stage for cuisine,” Shinichiro Takagi said. “That’s precisely why vessels rich in variation shine so brilliantly. Furthermore, Kanazawa has long been a thriving center for the tea ceremony. It’s a place where discerning connoisseurs abound — merchants, tea masters, tea utensil dealers and National Living Treasures among the many craftspeople. As a restaurant, we’ve always paid a lot of attention to selecting our tableware in order to delight our unique clientele.”

The choice of tableware can say a lot about a restaurant’s local character and individuality. Next time you visit a Japanese restaurant, remember to savor not only the flavor but also the traditional crafts evident in the tableware.

SHINICHIRO AND JIRO TAKAGI

Shinichiro (right): Born in 1970 in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture. After graduating from university, he trained at Kyoto Kitcho before returning home. He succeeded as the second-generation proprietor of Zeniya. He is also involved in collaborations with chefs worldwide and children’s food education events. In 2017, he was appointed a goodwill ambassador for the promotion of Japanese food by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Jiro (left): Born in 1974 in Kanazawa. After training in the Kansai region, he returned home to become the head chef at Zeniya. In 2019, he was honored as a contemporary master craftsman by the minister of health, labor and welfare.

茶道を背景に発達した日本の伝統工芸の器。

日本の食器はほかのどの国のものとも違っている。たとえば、洋食器なら磁器で丸い形が多く、コース料理では同じブランドや柄のシリーズの器で統一されることがほとんどだ。一方、日本料理のコースでは茶懐石の影響から陶器、磁器、漆器などの質感や色柄、形も多彩な器を用いる。

また、名品を模倣した「写し」を贋作と区別して尊重する文化もある。日本料理は茶道の影響が強く、割烹や料亭では、そうした歴史の流れにある伝統工芸の器に触れられる。土地ごとにご当地食材を扱うのと同様、器もご当地の伝統工芸品を好む店がほとんどだ。伝統工芸が盛んな石川県金沢市の料亭『日本料理 銭屋』では九谷焼や輪島塗、現代作家のもの、骨董品を織り交ぜ、季節の意匠を施したものが使われる。バラエティ豊かな器を使いつつ、全体が調和しているのは「西洋と違って、日本では茶室に代表されるシンプルな空間が料理の舞台だから」と主人、髙木慎一朗は、その理由の一端を語る。

器には土地柄や店の個性も反映される。各地の日本料理店で料理とともに器も味わってもらいたい。

Return to Sustainable Japan Magazine Vol. 53 article list page